I have mixed feelings about my reading this year. On the one hand, I only managed 22 books, which is very few. Part of this is just down to our travelling patterns: mostly short weekend breaks, and no long holidays affording lots of precious reading time. On the other hand, when I did find time I’m pretty pleased with my selection. It was a good range, with lots of highlights, a nice mix between old and new, and plenty to recommend to others. So, here’s to another year of books!

Fiction

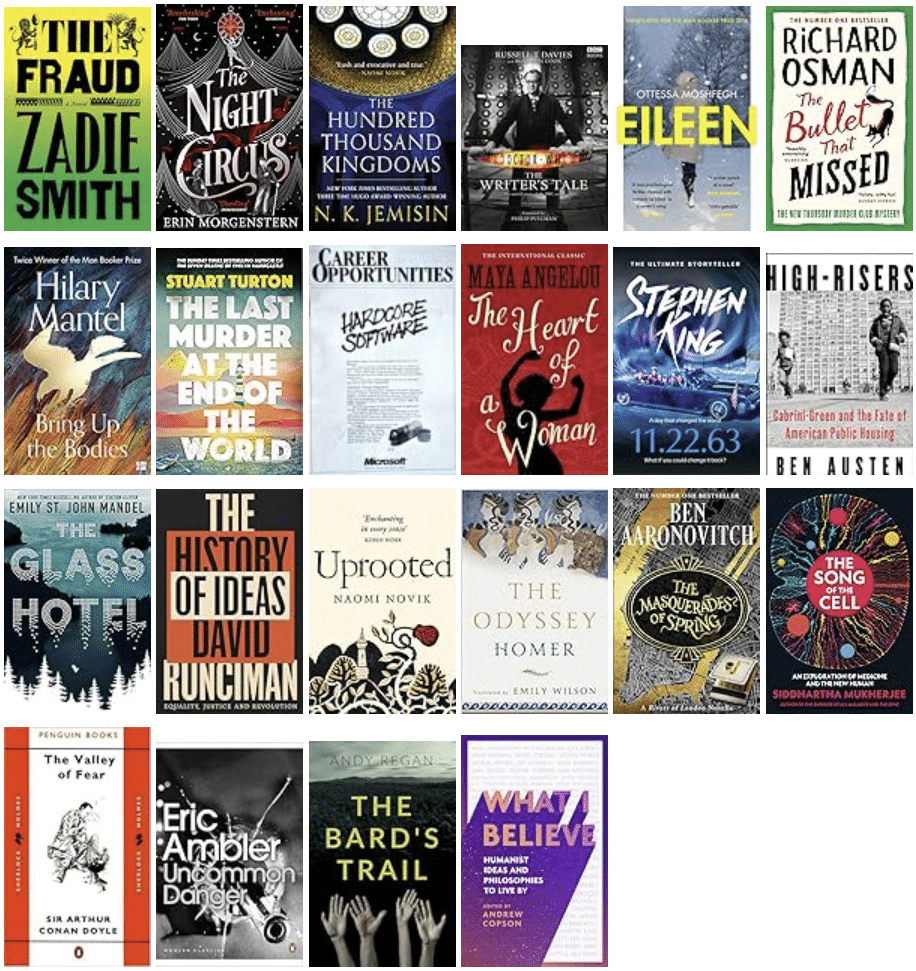

I loved The Fraud, my first book of 2024, not least because Zadie Smith has returned to writing about London rather than New York. Gloriously, even in this nineteenth century historical novel she manages to include the fields, farmers and ‘grassy Willesden Lane’ of Kilburn, Kensal Rise and that patch of North West London where we both grew up. I even loved the book itself: a signed, chunky hardback in a gorgeous cover and enigmatic black-edged pages.

Contained within those pages is a story based on the real-life Tichborne case, a fascinating example of Victorian populism in which a working-class man, and obvious fraudster, claimed to be the long-lost heir to a wealthy family fortune. Despite being convicted of perjury – or, rather, thanks to the widespread coverage of his trial – he received enormous public support, symbolising the empty claims of the justice system when the interests of the rich and powerful were challenged. Of course, the central conundrum is that if he really had been the missing heir he wouldn’t have been ‘a man of the people’ at all. So his folk hero status actually relies on the fact that, at some level, people must know that he’s lying to them, while still acting as a tribune for public anger and disaffection. The political parallels for our era are obvious, but this isn’t a preachy book, just an invitation to think deeply about what it means to be a fraud.

I also really, really enjoyed reading The Night Circus, by Erin Morgenstern, although I have no memory of how it ended up on my to-read list so I’m not sure who to thank. This is a dazzling fantasy about a magical travelling circus, which serves as the stage for a sinister contest between two young magicians who have not chosen to play and do not know each other’s identity. The only thing I wasn’t totally spellbound by was the romance at the centre of the plot, but then again, perhaps a romance isn’t always supposed to make sense. Regardless, this is highly recommended, and images of the night circus have lingered in my brain long after reading.

Sticking with fantasy, this year I also started NK Jemisin’s Inheritance trilogy with The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms, and my reaction was a resounding hmmmm. This was Jemisin’s debut novel and it very much reads like a rougher, first-draft version of her later The Broken Earth series, which I adored. A lot of the same ideas are there but it just coheres less well together, with certain elements – such as the love between Yeine and Nadahoth – happening too quickly. Yeine is meant to be investigating her mother’s murder, but the tension isn’t high enough because for most of the book she’s just waiting to die. With all that said, I’m still excited to keep going with the series, and perhaps my only real problem was reading Jemisin’s perfected version first.

I also did not love Ottessa Moshfegh’s Eileen. Dare I say it, but I think it was just too dark for me; or rather, too claustrophobic, with a very slow build up to a grotesque climax. It’s usually very annoying when a reviewer complains about “unlikeable” characters – it’s a book, not a date – but this really is the ultimate test of a novel constructed entirely of deeply, deeply unlikeable characters. Reader: this makes me feel old, but I failed the test. You may have better luck.

Talking of books being ‘too dark’: for years I’ve wanted to read a Stephen King novel. Since I’m really not a horror person, I picked 11/22/63 way back in 2017 as a nice time-travelling historical compromise, and this year I finally got around to reading it. Despite being long – really long – I did really get into this, even though the minutiae of Lee Harvey Oswald’s life never particularly grabbed me, and the central premise of the time traveller’s escapade – that preventing the assassination of JFK would lead to a transformationally better America – is so obviously ridiculous. Perhaps if Jake Epping had been a high-school history teacher, rather than a high-school English teacher, he would have figured this out sooner. Still, it was a lot of fun to read (barring the odd descent into overly-graphic violence) although coincidentally Trump narrowly escaped an assassination attempt while I was midway through, which was very weird.

Continuing some series from previous years – The Bullet That Missed was my favourite entry in Richard Osman’s Thursday Murder Club mysteries to date, and I (mostly) enjoyed the characters much more than I normally do. The plot was also the right balance of ‘clever, but not so clever that I couldn’t follow the ending’. Meanwhile, in Maya Angelou’s autobiographical series, I’ve reached book four – The Heart of a Woman – and my main takeaway is that her relationships are always so terrible!

Ben Aaronovitch’s latest Rivers of London novella, The Masquerades of Spring, was a lot of fun. Set in 1920s New York City (but not in an objectionable Zadie Smith way), the main character – Augustus Berrycloth-Young – is an entirely undisguised Bertie Wooster clone, so much so that it feels like an official crossover. And who wouldn’t want to read Augustus/Bertie bumbling around with Nightingale whilst investigating a haunted saxophone?

Over in rather more weighty universe, this year I also read the second book of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwellian epic, Bring up the Bodies, and the good news is that the sequel fixes her annoying writing habit from the first book of making it really ambiguous who is speaking half the time. Overall, I think I enjoyed this more than the first, helped by a tighter focus on a singular event. This novel is squarely about the downfall of Anne Boleyn, and while obviously her execution for adultery is horrific by modern standards regardless of what she did or didn’t do, all of the intrigue and plotting leaves me very curious about whether any of the confessions from her lovers – extracted under torture – contained any kernel of truth at all. A master study in the orchestrated downfall of someone who once seemed so powerful.

Stuart Turton’s The Last Murder at the End of the World is still not as good as his debut – The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle – but Emory is such a great hero to root for that I still kinda loved it. It also helped that the island setting was so vivid and evocative to me. It reminded me of that time in primary school when you have to draw a map of an island with coordinates, and I loved the idea of a single place with all of the world’s natural features – mountains! volcanoes! jungles! quicksand! – all crammed together. Anyway, this story is about the curious, inquisitive villager Emory trying to solve a murder in a post-apocalyptic world where everyone’s memories have been wiped. There’s also an omnipresent AI narrator, Abi, a countdown to humanity’s extinction thanks to a deadly advancing fog, and so many twists and turns that I would have to re-read the book to remember everything properly. But I can think of worse things to do…

I wish I had a better memory for plots in general, because then I would have enjoyed linking up the characters from Emily St John Mandel’s The Glass Hotel with its sorta sequel, Sea of Tranquility, which I accidentally read first in 2022. As it is, I still really enjoyed this novel about half-siblings Paul and Vincent, whose lives briefly converge while working at a hotel on Vancouver Island in Canada. Mostly, however, their stories are separate but intertwined, as Paul is forever haunted by a terrible incident from his student days and Vincent becomes a trophy ‘wife'(ish) to a Bernie Madoff-esque character who is running a giant Ponzi scheme. To be honest, I’m always nervous writing about Emily St John Mandel books, because I fear Todd will come running to ask what it was “really about”. I don’t know exactly, Todd, but I’m still down for another one.

I have so much to say about Naomi Novik’s Uprooted. This is partly just because I read it shortly after Randi, so we could actually discuss it while it was still fresh in our minds. But I was also struck by a well-written review on Goodreads by someone who absolutely loathed it thanks to the ‘abusive’ relationship between the ‘Dragon’ – a cold, seemingly ageless wizard who guards over the local village from his tower – and seventeen year old Agnieszka, the latest in a long line of village girls who is selected by the Dragon to live with him in the tower for ten years. Of course, in an obvious sense, the reviewer is clearly right, and I respect anyone who decides this book just isn’t for them. But fundamentally, the most magical thing about Novik – just as with Spinning Silver – is her ability to draw you in to a completely different, much more feudal mindset of interlinking rights and obligations which is utterly alien to how a modern character would experience the world.

If you can embrace this, then Uprooted is a gripping story about the development of Agnieszka’s own magic and the terrifying menace of the Wood. I loved the descriptions of magic being performed – the best I’ve ever read – and although the contrast between the Dragon and Agnieszka shades a little close to the ‘women are more natural and intuitive’ trope, Novik avoids making anything too one-sided. My main criticisms of the book are two-fold. Firstly, I did not buy Agnieszka’s friend Kaisa as a character. She seemed surprisingly underdeveloped compared to everyone else, and seemed to exist solely so that Agnieszka could be protective of her. Secondly, the magic system itself was too vague for me, so it was never quite clear why some things were possible and others were not. I also feel that the ‘corruption’ of the Wood could have been pushed even further. But these niggles just illustrate how strongly Novik’s writing implants itself in my head. Highly recommended if you enjoyed Spinning Silver (looking at you, Reema).

This year I’m also proud of myself for finally reading The Odyssey. And by gigantuan good fortune, I wasn’t far along before Randi and I happened to stay with a bone fide classicist over the weekend, so all I had to do to get answers to my dumb questions was look up from the sofa and ask. To be fair Emily Wilson’s translation (which we may affectionately term the ‘woke translation’ for its emphasis on slavery) is superb for rendering Odysseus’s adventures in crystal clear English. What really surprised me is how early his voyage concludes; Odysseus is back home long before the final verse, and after that his lengthy, drawn-out sequence of elaborate disguises and endless loyalty tests – before, spoiler alert, he murders all his mother’s suitors in a massive bloodbath – is less engaging. Well, less engaging to me. I don’t think anyone is reading this blog for an original take on Homer. Although, personally, my gut feeling is that since Odysseus is continually shown to lie about everything – to everyone! – that actually all of his stories are made up.

I’m still working my way through Sherlock Holmes – in a process which has been ongoing since 2010! – and this year I reached Doyle’s fourth and final novel, The Valley of Fear. This was a good one, actually, with its sinister second half about a murderous Freemason gang set in 1870s Pennsylvania. Even more fun was Eric Ambler’s Uncommon Danger, which is like all other Eric Ambler thrillers (amateur hero becomes embroiled in international intrigue) but is a particularly good specimen of the genre. Set in 1930s Austria and Czechoslovakia – including some genuinely tense nighttime border scenes – the indebted freelance journalist Kenton comes into possession of some incriminating Russian documents before alternating between capture (boo) and escape (phew). You’ll wish you were on the run, too!

Finally for fiction this year, I read my uncle’s second novel: The Bard’s Trail! This is quite different to his first one – a fast-paced political thriller featuring murder on a plane (which I read on a plane), competing spy agencies, international terrorist plots and (unsurprisingly) an excuse to feature a Champion’s League final match. I really enjoyed this, although I miss being able to pull my usual trick when reading thrillers: a reference plot summary from Wikipedia on hand to keep all of the characters and plot strands straight in my head. But it was a fun way to close out the year!

Non-Fiction

OK, so I’ve owned a copy of The Writers Tale for a very long time – ever since Russell T Davies autographed it for me and my sisters when it was first published. But I hadn’t sat down and read it cover-to-cover until this year, with all of my renewed excitement about Russell’s return to lead Doctor Who. And it’s a fascinating text. Davies is so unflinchingly honest – at times, you can just imagine an editor emailing to check “do you really want to put this in print?” – but I’m left with even more appreciation for the man who saved my favourite show.

It’s very rare for me to read any books in the work-related realm, but I couldn’t resist Steven Sinofsky’s Hardcore Software, which is really just a compilation from years of his Substack posts. (As a result it’s overlong and would have benefited greatly from editing – but this seems to be a signature Sinofsky trait. He’s always writing memos!) Sinofsky had a long career at Microsoft in product management, climbing the ladder to lead the development first of Office and then Windows, and I’m really 90% here for nostalgia for the era when these products were exciting and “releases” meant something. For the days when my dad would buy a new computer, and it would come with Windows 98 rather than Windows 95, and there were new and shiny things it could do. That said, even though the context of my job is very different, it’s also fun to be able to empathise with challenges and dilemmas which are universal to building any software product.

I’ve wanted to read High Risers for a long time. Published in 2018, it’s a book about one of Chicago’s most famous public housing projects: Cabrini-Green, home to somewhere between 15-20,000 people at its peak in the 1960s. The thing which makes this different to the other books about Chicago that I’ve read (Gang Leader for a Day, There Are No Children Here) is that Cabrini-Green wasn’t “over there” on the South Side, it was “right here” where I used to live and work in Chicago, and not very long ago at all. I mean, I literally shopped in the Target which was built over one of the demolition sites. So I’m implicated, in a sense, as the type of person who was “made room for” when these buildings were torn down and its residents were displaced.

And yet… the book is clearly not written as a simple elegy for these large housing blocks. I don’t know how anyone could do that in good conscience about a place where, by the end, children were in such danger from stray bullets. One of the uncomfortable truths which comes up again and again in these books is that in the heady early days – when the homes were fresh and new, when the political atmosphere was optimistic, when new residents were excited to escape abusive landlords – the authorities exercised a high degree of selection about exactly which families were allowed to move in. So while the initial community may be poor relative to the general population, it still benefits from not being the “housing of last resort” that it later becomes. One of the most hopeful parts of the book is a brief period when residents of individual buildings are allowed to take control of their own blocks and self-organise: an experiment which is sadly cut short by demolition. But it could have been a more sustainable model.

David Runciman’s The History of Ideas was an easy read because it’s just a written version of the second series of his ‘History of Ideas’ podcast, which I’d already enjoyed and recommend to anyone who is interested in political thought. Conversely, I’d never listened to Andrew Copson’s What I Believe podcast, but given that he was hosting me it felt rude not to pre-order his new book. This is an engaging series of discussions with prominent humanists about their philosophies on life: a quick read, and a nice tour through a lot of very reasonable people’s heads. My favourites were Nichola Raihani on cooperation (because I’d already heard about some of the research here about why different cultures have different attitudes about loyalty to kin, and it’s fascinating) and Ian McEwan on the novel being a “fundamentally secular” form. “If you want literature to worship God, then poetry is, I think, the perfect form. Otherwise, the monograph or the prayer and the hymn. The novel is too pluralistic for religion, too tolerant. It is indeed the ultimate humanist form.” I don’t know whether this is true or not, but it does give me a nice excuse for my lack of poetry.

Finally, I also read Siddhartha Mukherjee’s The Song of the Cell. I’d still recommend The Emperor of All Maladies as his greatest work, but you’re always in good hands with Mukherjee to guide you through the wonders of human biology with a reassuring doctor’s touch. As always there are lots of interesting facts which I quickly forget, but the overall impression is of the incredible ecology of cells working together to form one person like you. We’re used to thinking of the heart as “a muscle which pumps blood around the body”, but how do individual cells possibly form a mechanical ‘pump’? How does the immune system differentiate between the self and the nonself? We’re so fortunate to live in a world which has made so much progress in understanding how this works, and with so many people dedicated to taking us further still. And to be able to curl up with a book which summarises the past century or two of these discoveries is its own special joy.

I know what Glass Hotel is about. It’s about a bunch of loosely connected, barely developed characters, with their timelines presented all out of order to provide a sheen of profundity.