When lockdown began I did think that one silver lining might be having more time to myself to read. It didn’t really work out that way – sitting in the same room all day just isn’t that stimulating, I guess – so I’m closing out the year with a total of 35 books read which is a little down on last year. Still, I covered a lot of good books which I’m excited to share here, albeit with a heavy dose of comfort from reading ongoing series which I was already invested in. Mild spoilers below!

Fiction

I spent the whole of January reading The Wise Man’s Fear, the second installment in Patrick Rothfuss as-yet-unfinished Kingkiller Chronicles trilogy. The first book was my favourite read of 2019 and while the sequel was still very enjoyable it definitely suffers from ‘middle book syndrome’ of neither establishing the characters nor providing a resolution. Large chunks of the book feel like a frustrating side-quest which deviates away from the central story (the scenes with the Fae in the forest being the worst) but, of course, I will still be jumping on the third book with delight whenever it finally comes out.

Continuing with series, this year I reached the chronological end of Asimov’s epic Foundation saga with Foundation’s Edge and Foundation and Earth. The former was better, building to a wonderful climax where the Laws of Robotics suddenly re-emerge after a long, long gap: a cool and rewarding feeling of joined-up-ness with the first Asimov novels I started all the way back in 2014. The problem with the latter book is that – although Asimov has never been a character writer – Trevize is actively obnoxious enough to be distracting. There’s an amazing tease at the end, however, with the reappearance of Daneel, a decision to unite the galaxy against potentially hostile external forces and a hint that perhaps they are already among us. It’s a little sad that this is as far as Asimov went, although I’m looking forward to rounding off the series with his two Foundation prequels.

I also concluded Margaret Atwood’s post-apocalyptic trilogy with MaddAddam, which started really well but then went a bit heavy on flashbacks. To some extent this makes sense – things don’t tend to progress much in post-apocalyptic worlds – but it prevents character arcs such as Jimmy and Amanda from progressing as much as I’d have liked. Still, this was a great trilogy overall which doesn’t punish readers for taking a break between books. For a sequel which I enjoyed even more than the original, though, there was Becky Chambers’s A Closed and Common Orbit: the second in her Wayfarers series. I just immediately fell into this book – the same enthralling and optimistic world as the first one, but with a much stronger plot drive. It’s easy to praise sci-fi for being ‘dark’ but it takes skill to create something lighter without being lightweight, and I’m grateful for it.

And then there was The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, a prequel to the young adult Hunger Games trilogy. It was a decent enough read but suffers from the same problem as the Star Wars prequels: you already know that young Cornelius Snow’s journey is going to end in tragedy and evil, since he’s Cornelius Snow, so a lot of the book is spent just sorta waiting for that to happen. Plus his character does seem to swing a little wildly (even allowing for being a teenager) and the ‘romance’ with his Games mentee, Lucy Gray, is very creepy indeed.

In case you think all of my series are sci-fi and fantasy I also finished Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels this year with Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay and The Story of the Lost Child. They all blur together in my head as it’s all one long story, but I do remember feeling satisfied by the callback of the lost dolls at the end. Annoyingly I failed to make any notes about The Sympathizer but I was impressed by this North Vietnamese spy story (shades of Angela Carter about the Hollywood filming scenes) and unimpressed by my predictable failure to guess the identity of the commissar to whom the narrator is writing. Talking of spies: Eric Ambler is the gift who keeps on giving, years after Simon recommended him, and Epitaph for a Spy is another reliable interwar thriller of an ordinary man thrown into the deep end of espionage. The perfect pick-me-up.

When the country first went into lockdown it felt like the right moment for some familiar ‘London during WW2’ background vibes which Everything Brave Is Forgiven delivered well. To capture contemporary London I used to turn to Zadie Smith but sadly she now lives in New York and – perhaps this is Chicago rubbing off on me – I found the more New York-y episodes of her new Grand Union short story collection sparked some generic irritation in me. My favourite was ‘Big Week’… perhaps because it’s set in Boston instead.

Never mind, there are always London-based classics like Dickens’s Great Expectations to raise the spirits. Although we analysed the opening scenes to death in GCSE English I had never read the full book (or any Dickens novel) until now, and I’m so glad I finally did. He’s far funnier and snappier than I’d expected – in fact, reading this made me realise how perfectly Armando Iannucci captured the tone and humour of Dickens in his David Copperfield adaption. It is, of course, Dickens’s characters which shine brightest and it may or may not say something terrible about me that my favourite was the lawyerly but impressive Jaggers. It was also fascinating to learn about the controversy over the novel’s ending. The fashionable opinion seems to be that Dickens’s original, more downbeat ending is superior but, to me, the poignant final scene between Pip and Estella (which I had totally misremembered and was expecting to be a straightforward happily-ever-after affair) stays on just the right side of hopeful. Perhaps this is a strange comparison, but it reminded me of David Brent’s final scenes in The Office. Anyway: in conclusion, Charles Dickens is great.

I’ve loved so many of Ray Bradbury’s short stories but Fahrenheit 451 disappointed me. Counterintuitively, it’s more about the long-term effects of mass media on a population than the deliberate censorship which the title suggests, but it just didn’t click for me and suffers in comparison to 1984. Kafka’s The Castle, another classic, could also be frustrating but ultimately felt more meaningful. Kafka is very good at conveying the futility of the main character’s endless chase for what is simultaneously unobtainable and unimportant, and his writing is so immediately recognisable… although nowadays I can’t help but be reminded of Ishiguro which is a little backwards! (Side note: you know it’s been a stressful day of work when you sit down on the sofa and think “ah, yes, some Kafka is what I need”.) Meanwhile, landing straight in the “this is so much better than I thought it would be – why didn’t I read this long ago?” bucket is the 1950s British sci-fi classic The Day of the Triffids. The triffids themselves are perfectly nasty creations: carnivorous plants which will give you nightmares.

Piranesi, Susanna Clarke’s new novel after a long wait, was fantastic. I read it avidly in a few sittings and as it percolated around my head afterwards my admiration only grew. It’s a hard book to describe but has echoes of the famous Peter Capaldi Doctor Who episode Heaven Sent – a haunting, dreamy puzzle of a book with a complex, paradoxical message about innocence and faith which I could imagine really struggling with but absolutely loved. Gilead, on the other hand, is a book about faith which I deeply admire but cannot quite connect to in the same way. Written as a series of letters from a sick, elderly Reverend to his young son, there’s nothing for me to criticise or critique – and I do sense the meditative beauty – but at the end of the day it’s something like Piranesi which really sticks with me.

I was also engrossed by the latest Cormoran Strike novel, Troubled Blood, staying up late on the sofa to keep reading it while trying not to get too creeped out. Sadly the ongoing controversy around JK Rowling casts a shadow over the communal enjoyment of a series like this, but within the fictional world of Strike and Robin it is always exciting to be amongst old friends and see their relationship moving along. Similarly, it was nice to be back with magician copper Peter Grant in Ben Aaronovitch’s Lies Sleeping. I’m now at book seven which felt like the end of an era, with resolutions (perhaps!) for both the Faceless Man and Lesley May. Still, there’s more to come, which is just as well since the brief outing of German policeman Tobias Winter in The October Man novella proves that Aaronovitch really can’t let go of Peter’s narrative voice even if he tries.

Finally, though, I’d really just like to sing the praises of NK Jemisin’s The Broken Earth trilogy, or at least the first two parts (The Fifth Season and The Obelisk Gate) which I read this year. Where to start? These books have been on my to-read list for a while but especially so after her worldbuilding podcast episode with Ezra Klein. And it’s true, the worldbuilding is incredible here: from the big-picture – a geothermically unstable supercontinent where a persecuted few have the power of ‘orogeny’ to manipulate seismic events – to the smallest details. There’s no ‘Mother Earth’ here: it’s Father Earth, or Evil Earth, although my favourite example of these worldbuilding touches has to be the customary drink ‘safe’ which reacts to foreign substances by changing colour. But Jemisin hasn’t just created an intriguing world – there’s also a rip-roaring plot, an epic, tragic, multi-millennial intrigue and characters who are complex, layered and believable. It’s not all easy reading; the violence is well-written enough to make me flinch. But I have really savoured these books so far and cannot wait for the finale.

Non-Fiction

If I only had one non-fiction recommendation this year it would be Mehrsa Baradaran’s The Color of Money, which traces the history of the racial wealth gap in the US through the prism of “Black banking” and “Black capitalism” initiatives. It might seem odd to focus on these small and often troubled banks given how miniscule they are as a share of the overall economy, but Baradaran’s whole point is that the policy obsession with these concepts (most recently as ‘Enterprise Zones’) is a wasteful detour because they simply can’t function as normal banks which multiply wealth by lending out money. Anyone familiar with the racial wealth gap – and holds it carefully apart from ‘income’, which is very different – will know that it always comes back to segregated housing, particularly Black homes which did not appreciate in value or benefit from federally-backed mortgages. I loved this book for many reasons, one of which is its careful academic grounding in politics and economy of the US, so readers should avoid copy-and-pasting its conclusions to the UK or elsewhere. But the relationship between housing, banking and credit is deeply significant in Britain too and worth reading about in detail.

My mandatory entry in the ‘Political Thought’ series this year was Max Weber’s Political Writings, which I looked forward to because Weber is a legend and everyone has their favourite Max Weber quotes. (OK, perhaps not everyone.) In the run-up to his most famous essay on ‘The Profession and Vocation of Politics’ – which is well-worth reading alone, particularly if you’re lucky enough to have David Runciman’s explanatory lecture appear in your podcast feed at exactly the right time – I pocketed my own nuggets: on purity politics (“the right… to enjoy the intoxicating thought that ‘the world is full of such dreadfully bad people'”), the inadequacy of referendums (“most conflicting reasons can give rise to a ‘no’ if there is no… process of negotiation”) and non-parliamentary systems (“the voter is deluded as to the true identity of the person guilty of maladministration”). I’m not saying I read Weber solely to confirm my own biases… but who can resist indulging a little along the way?

Sticking with a politics-heavy year, I also read John Bew’s long but worthwhile biography of Clement Attlee, Citizen Clem. Attlee is a bit of a weird figure in British politics because his legacy is totemic, and many different groups now claim his legacy as their own, but unlike Churchill or Thatcher it’s hard to get much of an impression of what Attlee as a person was really like. In his day he often cut an uninspiring, uncharismatic and compromised figure – indeed, you get the sense that Bew is constantly apologising for picking someone so ill-suited to a heroic biography. The constant sniping from Attlee’s contemporaries, whose political heirs now appropriate his image, would have made this book too painful to read before Starmer’s election as Labour leader. But now there are glimmerings of hope that the real tradition of Clement Attlee, as he actually was, may yet emerge in British politics once more.

Gang Leader for a Day is unusual for a book about Chicago’s housing projects in that it’s (mostly) not written to shock. Set in the Robert Taylor homes (since demolished, but the aerial photos remain breathtaking for how large and other-worldly they were) it has some fascinating insights into the economics, management styles and gender dynamics of the gangs which operated there. (I was particularly struck by the minimum wage rates for frontline dealers.) Meanwhile, in North Korea, A Kim Jong-Il Production is less insightful but is gifted with the incredibly strange true story of the kidnapping of a famous South Korean movie couple so that they could make films for Kim Jong-Il. I hadn’t realised just how many kidnappings were orchestrated from North Korea and will never forget learning about Kim’s personal global film piracy operation so that he (and he alone) could enjoy foreign cinema.

Finally, Katie gifted me Randall Monroe’s brilliant What If? for my birthday, or “serious scientific answers to absurd hypothetical questions”. It’s the kind of book which makes you want to interrupt other people’s reading with interesting facts (sorry!) but the two which really stuck with me are the all-female species of salamander who reproduce asexually but use a courtship ritual with male salamanders from related species as a simulated ‘trigger’ to breed and Randall’s musings on how throwing a ball is actually really hard. No, seriously, the length of time for nerve impulses to travel down your arm is much longer than the half-millisecond timing error which would cause a baseball pitcher to miss the strike zone…

As I suspected, moving continents took its toll on the number of books I read this year, although this was balanced out by lots of uninterrupted reading time during our travels and I finished at a respectable 38. And if Robert reads this, I’m sure he will already be banging his head against a desk saying that I should be counting quality over quantity anyway. So without further ado, here was my 2019 in books:

Fiction

I began 2019 in fine style with The Goldfinch, the most recently-published of Donna Tartt’s three novels and, sadly, likely to remain that way for a couple of years yet at least. It’s a long book, but well paced, and I thought a lot about the characters in-between reading sessions – no doubt partly because we were hiking through Torres del Paine National Park at the time. I’ll never forget waiting for the catamaran when a big plot twist occured, or coming to the end of the story while lying in my sleeping bag on our last night of camping, just as raindrops began to gently pitter-patter on our tent. I was also pleased that the book ended with less despair than I thought it would, and once we got back to civilisation I really enjoyed looking up the eponymous goldfinch painting.

The Grapes of Wrath had been lying on my to-read shelf for years and I think I had built up a bit of a phobia of it, partly due to Mr. Buchanan’s volcanic demolition of the very idea of using it for my comparative AS English essay. In the end I was pleasantly surprised, and the combination of Steinbeck’s scenic descriptions and his characters’ distinctive dialects creates an extraordinarily vivid world. Whatever else you make it, the relationship between Tom and his Ma is quite beautiful. If I was feeling in an AS English-y mood, I might compare it favourably to the relationship between Ignatius and his mother in The Confederacy of Dunces, another classic American novel which I had procrastinated about reading but one I suspect Mr. Buchanan would have enjoyed rather more. It was Todd who recommended this to me, way back on one of the staircases to the 6th floor of the Groupon building in Chicago, and I’m glad I got there eventually because it is very funny. The spoilt, delusional Ignatius is an utterly compelling character – albeit repellent and obnoxious at the same time – although I’m afraid I’m the type of person who unequivocally wanted him to be captured at the end of the book rather than cheered on the exploits of the ultimate anti-hero.

When I got back to London I found that everyone was reading Normal People on the Tube, and as usual there is some wisdom in the crowd. This is an engaging novel which flits between the minds of Connell and Marianne like a fly, mostly avoiding big moments of drama in favour of the little things which make up a realistic teenage relationship. I loved the way it captured the complicated, not-one-thing-or-the-other type of bond which can only really form between two people at school but then stays with you forever. Another great novel about relationships this year was An American Marriage, the story of a relationship wrecked by a wrongful conviction and imprisonment. When reading this you really, really want everything to work out – why can’t everything just go back to the way it was? – but of course it can’t, no matter what the formal language of justice would say, and it’s a gut-punch.

When I read Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere last year I failed to write any notes, so after finishing Everything I Never Told You this year I was determined to remember a little more. I think my feelings towards both books are similar, though: I really enjoyed reading them, but I do struggle to believe in the characters. Would the sibling relationship between Nath and Lydia, for example, really blossom after years and years of being parented so differently? But these aren’t meant as criticisms, just… wonderings. I am happy to criticise Robert J. Sawyer’s Hybrids, though, the third of his Neanderthal Parallax trilogy which opened so well but is a classic case of putting all of the interesting ideas into the first book. By the end it’s the rather tedious religious question which becomes central to the plot: a shame, because it’s by far the least interesting part of the whole thing.

Conversely, I failed to love the first of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels last year but am so, so glad I kept going with The Story of a New Name in 2019. Essentially, the problem is that the author considers the whole thing to be one long novel, so the beginning is slow with a lot of build-up but by the start of the second book you can just get straight to the plot. The friendship between Lenù and Lila is an incredible literary creation and I can’t wait to see how it unfolds further next year.

In 2019 I also completed Chinua Achebe’s African Trilogy with Arrow of God and No Longer At Ease. I’ve totally stolen this point from the introduction, but it is true that it’s the metaphors and proverbs from Arrow of God which get inside your head after a while and make the biggest impression. The fact that the scenes from the perspective of the colonial administration were much easier for me to follow (with familiar-looking names that didn’t require any checks in the glossary) than those in the villages speaks volumes about having cultural reference points. Anyway once I got into this book I preferred it to the original Things Fall Apart. No Longer At Ease jumps forward to the late 1950s to when independence feels close and takes another look at cultural clash, this time between the push-and-pull of forces which lead a good man to accept a bribe and fall into corruption. These aren’t always easy books to read, but I’m glad I did.

I’ll tell you what: The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle is amazing fun, and I’m very grateful to Katie for lending me this time-travelling, body-swapping murder mystery as I didn’t want to put it down until the puzzle was solved. Katie also recommended The Long Way to a Small Angry Planet which I have mixed feelings about. The characters are adorable, the inter-species worldbuilding is clever and thoughtful and I do appreciate that the unlikeable jerk on the ship happened to be named Corbin. (Jokes!) I just didn’t love the plot structure meandering between different standalone ‘incidents’ rather than a clear overriding narrative, although I will happily come back to the series for more. As for Neil Gaiman’s Trigger Warning – a collection of short stories – it was the book that came back to me for more, as when I fell asleep in Vietnam after reading one of his tales set on the Isle of Skye it promptly continued to unfold in my fevered nap-dream. It’s what Gaiman would have wanted, I guess?

All books in the sci-fi genre owe some sort of debt to Asimov, and this year I reached Foundation and Empire and Second Foundation in his Foundation series. This may be completely off-base, but when I picture the Second Foundationers quietly pulling the psychic strings of the universe behind the scenes it definitely makes me think of the bald guys from Fringe. I also read Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness which is surely a masterpiece of science fiction, and plunges into the cultural alienation of a visitor to a hermaphrodite species on a very cold planet. Unlike the Neathanderthal series there are no glaring chunks of exposition, but instead so many layers and so much to think about. Highly recommended.

Homegoing begins in an eighteenth century African village which becomes involved in the slave trade – not a perspective I can remember from a novel before, and it felt like discovering the missing first half of Octavia E Butler’s Kindred in the sense of better understanding where American slaves were taken from. Each chapter of the book then moves forward through the generations and between two different strands of the same family, which means that you only get a thin slice of each character. By the end the story had passed through so many lives that the earlier generations were just a hazy memory… which, in a sense, is just like real life. The ending of the book is perhaps a little neat and contrived, but otherwise I really enjoyed this.

Contrary to expectations, I also really got into My Year of Rest and Relaxation. If you simply describe the plot (wealthy New Yorker medicates herself to sleep for a year) it doesn’t sound very compelling at all, but the writing is incredibly engaging and completely sucked me in. It also helps that the book is fairly short and doesn’t overstay its welcome. Conversely, while it usually takes me a while to get into ‘epic’ multi-generational books like The Glass Palace, in this case I’m not sure I ever truly did. I don’t have any specific complaints (aside from the last few chapters where it felt like the author was rushing to lay out all of the remaining story) but it just never became as compelling as both the plot and the characters should warrant. That said, I did appreciate learning more of the history of Burma/Myanmar and was pleased when I kept recognising locations (Penang! Butterworth! Cameron Highlands!) from our travels.

The Year of a Flood is an excellent sequel to Oryx and Crake, although it’s actually more of a parallel retelling of the same events from other perspectives: this time, those of the masses in the ‘pleeblands’ and the environmentalist cult of God’s Gardeners. Atwood continues to build out her astonishingly well-developed world here, and my only frustration when reading it was that as Amanda had lent me her Oryx and Crake paperback I couldn’t go back to check the original references to the main characters! I certainly had no memory of Ren/Brenda at all, but although I believe that she only appears very fleetingly in the first book it is satisfying that her diary message for Jimmy exists in both to tie the plots together.

I also made a very welcome return to world of His Dark Materials with The Secret Commonwealth, the second installment of Philip Pullman’s new trilogy. From the very beginning, I was captivated (and devastated) by the notion of Lyra and Pan falling out and not talking to each other, and it was wonderful to see the world open up as the plot went on as Pullman pushes open the door wider than the very narrow story of the last book. That said, I don’t feel that he really nailed Lyra as a 20 year old: her philosophy doesn’t ring true given her own experiences in the original trilogy, and there are definitely some badly-handled sexual themes. It also ends at a sudden juncture mid-plot! Nonetheless, I did really enjoy it, and at the end of the year I snuck back into Pullman’s world one more time with Once Upon A Time In The North – a wonderful novella which tells of the first meeting between Lee Scoresby and Iorek Byrnison.

But my absolute standout favourite book of the year has to be Patrick Rothfuss’s The Name of the Wind. I remember very clearly the night in Motel Bar in Chicago when Teresa recommended this book to me back in 2016, and I finally started reading it during the Torres del Paine trek as I thought a fully-fledged fantasy novel would be well-suited for hiking and camping. I was rewarded with the first part of this classic and absorbing tale of the heroic Kvothe – seasoned, to be fair, with a fair dose of wish fulfilment – and after exercising a lot of willpower to avoid reading the sequel immediately, I am now very excited to return to the world of The Kingkiller Chronicles as soon as I can in 2020.

Non-Fiction

My first non-fiction book of the year was Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal about end-of-life care. It’s the kind of thing that we would benefit from discussing more openly within families before a crisis hits – indeed, that’s really Gawande’s whole point. He writes persuasively about the extent to which children will usually ‘choose safety’ and maximum medical intervention for their aging parents – even though they would usually prefer freedom and independence for themselves – although this does glide a little too easily over what happens with mental as well as physical decline. You probably won’t be super-excited to pick up this book, but it’s worth thinking about.

On a much lighter note, Time Travel: A History is a very well-written guide to the concept of time travel and its history across science, literature and culture. But it’s also written in an unnecessarily acerbic tone, and rather disdainful of a genre that so many people could have written about with a lot of love. I loved reading it – because I love time travel! – but I could have done with a friendlier guide. G.H. Hardy is much more enthusiastic about his chosen subject, mathematics, in his very short classic A Mathematician’s Apology. I decided to read this after seeing a play about Hardy and Ramanujan in Chicago and it’s a difficult book to review, but given its length it is well worth giving it a go.

The first chapter of Boss, Mike Royko’s classic text about longtime Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley, brought me vividly back to the city with its descriptions of its architecture and, sadly, its horrible freeways. Everyone knows that Chicago’s machine politics is ugly and corrupt – and this book will only confirm how depressing the city’s history is – although shortly after I finished it the city did elect a black, female and lesbian mayor so, even though a figurehead is not everything, that did feel like… something.

Giles Tremlett’s Ghosts of Spain was OK, but just OK. I read it because I wanted to learn a little more about modern Spanish history, and now I do understand a little more about modern Spanish history – especially the ongoing ghosts of the Civil War – so that was useful enough. For some reason I just didn’t love his writing style. And although it’s probably unfair to mention this one tiny thing, his use of the word ‘poetess’ at one point made me cringe. Punch and Judy Politics was perhaps exactly the opposite. I didn’t really need to learn anything about Prime Minister’s Questions – who does? – and the reason the authors can get so many gossipy interviews about it is because almost everything that happens in PMQs becomes unimportant immediately. But gossip is fun, obviously, and there were one or two insights into contemporary politicians which I found to be very revealing.

Parliament has changed a lot since the rule of King James VI/I, and yet – as ever – reading his Political Writings will throw up oddly modern moments. James was King of both England and Scotland as two separate countries, and although his speeches urging unification were ignored, reading them gave me a bit of a tingling feeling given how close to the end of said union it now feels that we are. On other topics, James has the force of conviction you would expect from a monarch whose principal position is the divine right of kings. For example, he advises his son not to duel, not to allow guns at court and not to believe that rhyming is the most important part of poetry, which to my mind is all pretty good advice. But he also instructs him to eat plenty of meat without any sauce – because sauces are somehow decadent – which is what comes from being King and never having anyone turn around and tell you to stop talking and just give the sauce a try. He’s pro-bridges, pro-roads, pro-schools and pro-hospitals but also anti-pubs and – amusingly – anti-London, which he thinks is too big and too powerful. “Even so now in England, all the country is gotten into London; so as with time, England will only be London, and the whole country will be left waste,” he complains. You may have heard that before.

Finally, two horrors of the twentieth century are explored in Adam Tooze’s The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy and Philip Short’s Pol Pot: The History of a Nightmare. Tooze has the more honest title – this really is a book about the Nazi economy rather than a general history – and the overriding message is not only that Nazi Germany was completely outmatched in economic and industrial production during WW2 (especially once the US joined the war) but that its leaders knew this full well. And yet they ploughed ahead anyway, in the spirit of “the gap is only going to widen”, with predictable results. The statistical focus makes the narrative a bit of a slog to get through at times, but it’s a memorable analysis and there are some truly illuminating moments when the horrific contradictions of Nazi war aims (for example, extermination versus slave labour) are brought into direct conflict with each other. If you only have a casual interest, this is probably one to file under “find a good podcast about instead”.

In comparison to Nazi Germany, Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia is only glancingly mentioned in modern British culture, so after visiting the Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh I felt compelled to start reading up on it immediately. Like all civil wars it’s a complicated story – much more complicated than any story told through the simple “West vs. USSR” schema. I said that Short’s title was less honest because this is not really a book about Pol Pot himself, but rather the whole painful story of how Cambodia came to be ruled by what began in the 1950s as a rather hare-brained Parisian student group but went on to seize power and then murder nearly a quarter of Cambodia’s entire population. It’s never a good idea to try and rank atrocities alongside each other, but there are certain aspects of the Khmer Rouge regime that were so extreme and so crazy – their abolition of currency, their forced evacuation of the entire capital city for the countryside – that make them particularly grimly fascinating. Short’s book is a perfectly good guide, but however you choose to learn about it this is an awful but compelling part of our very recent global history.

Time for the annual book review post, which has grown longer and longer since I started in 2012! For another year running I met my annual target – “at least one more book than last year” – by reading 42 books (a great number) in total. This was definitely made a little easier by having extra free time in December. For 2018 I also instituted an extra rule of alternating between male and female authors after noticing that last year’s bookshelf was pretty imbalanced in favour of men.

Since 2019 is going to be such a transitional year – with all of our travelling and moving back to London – I have decided to take a break from my reading rules and targets. I’m still planning to read – a lot! – but I’ll just see what comes naturally, and maybe go back to normal in 2020. And without further ado, here’s my 2018 bookshelf:

Fiction

I started the year with Americanah, which left me a little flat. People have been surprised by this, especially given how much I enjoyed Half of a Yellow Sun, and it’s not that I have any particular critique of the novel. It was well-written and enjoyable to read but just didn’t leave me with much afterwards. I then moved on to my traditional annual book recommendation from Todd, which this year was The Virgin Suicides. This was an unsettling read, clearly written in a different era, and the collective ‘us’ narrating the book is deliberately creepy. I have to say, I was never into the fetishisation of suicide which sometimes exists among teenagers, and structuring the book around the suicides of five sisters struck me as more totally horrific than maybe it does to a younger audience. Sticking with recommendations: I did enjoy Nina is Not OK, which came via Tash and felt very true to life.

The Power was excellent, centred around the very raw and mostly unspoken question: just how much of the modern relationship between men and women is based on the underlying awareness of physical strength? It reminded me a little of Exit West in that it uses a spark of sci-fi/fantasy to probe a big social question, but does so a lot more successfully. In a similar vein, I was excited to enter Margaret Atwood’s dystopian (and highly developed) world of Oryx and Crake and am looking forward to the rest of the series.

Let’s talk about Tess of the D’Urbervilles, because Tess’s life is really depressing… a shining example of when to just pack up and move to America. It’s impossible not to feel deeply for Tess and the unfairness of her life, and the force of fate which pushes her relentlessly from bad to worse to even worse, even though there are plenty of moments where things are – maddeningly – almost-but-not-quite rescued. The book also paints a vivid picture of English rural life – although, of course, I don’t feel the same sadness about its passing that Hardy does.

When it comes to Ishiguro I can’t stop myself working through his back catalogue, even when it means reading something as frustrating as The Unconsoled. It’s a dream world – that’s all you need to know. The kind of nightmare where space and time is all warped and you keep taking on new missions without ever completing anything. In comparison, I enjoyed reading Purity a lot more but it is also the weakest Franzen book so far, especially once it starts dragging in the second half with the memoir section. Also, can we please institute a complete ban on fictional characters in novels who are authors?

In contrast, Lethal White was so, so good and my favourite of the Cormoran Strike series so far. The novel was satisfyingly long, giving me more time with Strike and Robin after a far too prolonged absence, and the ending was less of a headtwist than usual… not that I saw it coming, but I felt that everything fitted together better plot-wise than the predecessors in the series. More please, JK Rowling, and soon!

I was a little disappointed that American classic A Wrinkle In Time is not actually a time-travel story (more of a space-travel story!) but it was cool as a piece of children’s fiction with a strong protagonist. The explicitly Christian message (and some overly obvious Cold War rhetoric) can be a little off-putting, and it is funny that the big bad is called IT, which now sounds more dreary than sinister. Sticking with the American sci-fi theme, The Golden Apples of the Sun – the third and final anthology by Ray Bradbury in the beautiful collection gifted to me by Katie a few years ago – was another amazing collection of short stories. Almost all of the stories manage to convey a complete, vividly-imaged world in just a handful of pages. The other short story collection I read this year was The Ladies of Grace Adieu, Susanna Clarke’s brief return to the world of Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell. I enjoyed these fairy tales, but I’m also up for a full-throated sequel.

I’m not really sure how I feel about My Brilliant Friend, which has been extensively recommended. The central characters were certainly interesting and I will keep reading the series to follow their lives, but I wasn’t nearly as gripped as many reviews suggested I should be. Similarly, Paul Auster’s ‘New York Triology’ (City of Glass, Ghosts and The Locked Room) are the kind of unsettling and frustrating postmodern books which are good to read occasionally, but I really don’t love, and I’m worried that the Amazon and/or Goodreads algorithm is going to start sending me more.

The book which really rubbed me up the wrong way, however, was London Fields. I had enjoyed Time’s Arrow so picked this up as my next Martin Amis novel. It is, supposedly, regarded as his “strongest”. But it’s a car crash. Yes, it is well-written, but the good writing is just directed at being snide and cynical for no real purpose. It’s also endlessly racist and misogynistic. At this point I can imagine Amis popping out to complain that I’m being unfair because it’s the narrator character who is racist and misogynistic, not him. No dice. All the vitriol does nothing other than to furnish a vague and confused “state of society” critique for the “end of the millennium” [sic] which had already dated very badly by the end of the actual millennium since the book was written in 1989, anticipates literally nothing of the 1990s and anachronistically chucks in threats of a nuclear war between the Cold War superpowers.

OK, assuming I’ve persuaded you not to read that, what should you read instead? Kindred (a time-travel story from 1979 about a black American woman who finds herself back in a nineteenth century slave plantation) is powerful and very brutal. The Queue is both Orwellian and Kafkaesque, but set in a modern day Middle Eastern bureaucracy which is clearly Egypt. And I want to put in a good word for HG Well’s The Invisible Man, which is a short, fun classic of sci-fi about (unsurprisingly) a man who manages to turn himself invisible. Unfortunately, he turns out to be the worst, most petulant guy imaginable so the opportunity for superhero stunts is entirely wasted.

Finally, a few words for the authors who always make it onto this list. I planned to read Asimov’s classic Foundation years ago but decided to methodologically work through his interlinked Robot and Empire series first. This year I finally got there and while the underlying premise is slightly bonkers, I am reassured to have many books left in the series to enjoy. And I have almost caught up with Ben Aaronovitch’s Peter Grant series! The sixth instalment, The Hanging Tree, felt a little rushed at the end but did move the overarching plot along significantly and entering this world is always a treat.

Non-Fiction

A couple of my favourite non-fiction books this year have been recommendations from Vox’s The Weeds podcast, starting with Dreamland. It tells the intertwined story of the rise of opioid prescribing in the United States (most notably OxyContin) and, simultaneously, the revolutionary ‘customer-centric’ approach of the Mexican heroin trade, for example through salaried dealers who have no incentive to dilute the product. The result has been an opioid epidemic of devastating proportions. An excellent read – perhaps the only thing missing is a deeper examination of the origins of the physical pain driving the initial prescriptions in the first place.

Similarly, Ghettoside told a simple but effective story about murder in the most violent areas of LA. While many people are familiar with police violence in black communities, the other side of the same coin is chronic under-policing where it really matters. Clearance rates for murder are shockingly low, and we know from research that consistency of punishment is much more important for reducing crime than the harshness of the penalty. The homicide detectives in the book have low status even within the LAPD, but justice can’t be done without them. All in all, along with the powerful stories of wasted lives, the book is a good rebuke to the idea that only preventative policing is valuable.

I also really enjoyed Crashed by Adam Tooze – although that’s unsurprising, since I always enjoy his work. This book runs through the decade following the 2008 financial crisis, and the most memorable theme is the poor preparation and reactions of European institutions in general and Angela Merkel in particular. I think perceptions of Merkel are rose-tinted in a world of Trump and Brexit, and she may be personally sympathetic, but it’s still amazing to contrast Europe with the US Federal Reserve. The consequences (most obviously in Greece) have been dire.

I read A Spy Among Friends – about the notorious spy Kim Philby – after being inspired by a John le Carré novel a few years ago. It’s really just totally crazy that the guy running anti-Soviet intelligence for Britain was a Soviet spy the whole time. Astonishing. Sticking with a Soviet theme, How Not to Network a Nation is an interesting story about the aborted creation of a Soviet internet to manage the economy. It reminded me of an Asimov short story about globalised central planning by computer. At the same time, this is very much one of those academic books to which someone has given a snappy title and slapped a nice cover on. I could have done without the repetitive pondering.

The Guns of August is a classic of popular history, but I was expecting something more political. Instead, most of the book is taken up by the military history of the first months of the First World War, and the events which quickly led to a stalemate with no decisive victory for either side. Interesting, but not really the focus I wanted. On the other hand, Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl was absorbing and a really emotional read. Obviously you feel really badly for Anne’s mother, who is treated pretty harshly by her daughter, but I don’t think that makes Anne ‘unlikable’ as opposed to a teenager who was robbed of the time to grow up. The worst part is getting to D-Day: she is so excited that the invasion has begun, while the reader is just counting down the months until August when the family are discovered and the diary stops.

No, I haven’t read Democracy in America yet. Yes, it’s on my list. As a warm up, I read Tocqueville’s The Ancien Régime and the French Revolution instead. His writing (at least in this translation) is very fresh and easy to read, and the key point is worth repeating: “it is not always going from bad to worse that leads to revolution… the most dangerous time for a bad government is usually when it begins to reform… every abuse that is eliminated seems only to reveal the others that remain”. (Admittedly the logic for rulers of bad governments is not great.) Equally, his passage on the feudal nobility – who once possessed greater privileges, and yet were less unpopular because they provided services in return – has interesting implications for government today.

Tara Westover’s Educated (yes, the book on every reading list) was not quite the memoir I expected. Based on her interview on the Talking Politics podcast I was anticipating an upbringing which was extremely cut-off from the rest of the world… but not necessarily one which is so straightforwardly violent and abusive.

Finally, I really loved The Prodigal Tongue, a book about American and British English which grew out of Lynne Murphy’s awesome Separated by a Common Language blog. It’s so nice to read a non-alarmist, well-informed and evidence-based exploration of English in two countries by someone who obviously loves language. Better than 95% of anything else you will read on the topic.

I read a record 40 books in 2017! In an exciting innovation this year, one of these books – The Stars Move Still – was written by my uncle. It’s a fictionalised portrayal of a forgotten American tragedy, and you can buy it now. Let’s take a look at some of the others…

Fiction

As is apparently traditional, I kicked off the year with a gift from Todd: Fates & Furies, two very different perspectives on one marriage which really does make you flip back and re-read sections again in a new light. I was also excited to read Zadie Smith’s new novel, Swing Time, although I found myself much more interested in the central relationship between the narrator and her childhood friend Tracey than the subplot with popstar Aimee.

Early on in the year I also ploughed through The Idiot – it’s only taken me a decade since Mr. Drummond first told me to read it during A-Level history class – and my main takeaway is that Lizaveta Prokofyevna is amazing. I absolutely love her outbursts, and she is very welcome at my literary dinner party. The book is also noteworthy for its discussion on criminality and liberalism, which could easily be written today. It was equally striking to find the actual terms ‘feminism’ and ‘human rights’ in Howards End (from 1910) although the plot and characters were not hugely compelling.

This year I continued my quest through Asimov’s interconnected series, starting with Susan Calvin origin stories in The Complete Robot (along with other memorable robot tales) and continuing through his Galactic Empire books. They are always enjoyable! I also read another two instalments in the Peter Grant series, Broken Homes (a big twist of an ending!) and Foxglove Summer (a detour into the countryside). It’s been a much longer gap since I last read anything from the His Dark Materials universe, but La Belle Sauvage – the first in a new trilogy – was a joy. The story is small in scope, but a confident return to the world of dæmons and Dust.

Abbi’s sci-fi recommendation, The Gone-Away World, was a post-apocalyptic wild ride with definite shades of Vonnegut. Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, which had sat forebodingly on my to-read list for a while, is a giant tome but with an incredible premise and story. Susanna Clarke crafts a compelling alternative history of England divided between Northern and Southern kings, with a lot of folklore, huge attention to historical detail and magic which is beautifully integrated into the world.

However, my favourite piece of speculative fiction this year was Hominids – a story about a Neanderthal man who accidentally crosses over from a parallel universe in which Neanderthals survived rather than humans. I feel a little guilty naming this as my favourite because as a work of literature it is definitely not the best. There’s a definite ‘genre sci-fi’ feel where interesting ideas and discussions take precedence over plots or characters, not to mention a clumsy rape scene which is not handled well. Despite all of this, I just really really wanted the whole thing to be true so that I could talk to a Neanderthal. The impact of small biological differences between the two species, such as a stronger Neanderthal sense of smell, are fascinating when the author imagines how their civilisation would differ as a result. And it left me feeling a bit bad about being a homo sapien. I will never use ‘neanderthal’ as an insult again.

I am pathetically bad at predicting where a plot is going to go, so it was exciting to be able to read The Girl on the Train and work out the killer for myself, albeit taking 70% of the book to get there. Eric Ambler’s Journey Into Fear was another straightforward thriller, and super enjoyable. Before The Fall was also a compulsive read, piecing together the mystery behind a plane crash, although the ending was a little anti-climactic as various open plot threads and red herrings were left hanging open.

I confess that I only made a note to read Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglas after Trump memorably said he was doing an ‘amazing job’, but everyone should take the time to read this searing first-hand account of American slavery. To continue the theme of reading good books for bad reasons: I was spurred into reading Maya Angelou’s I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings by a 1-star Goodreads review in which the mother of a 15-year old boy objects to the ‘sordid details’ he is ‘forced’ to read about for school. She finally compromises by telling him ‘which chapters to skip’. I guess I owe this woman something, because I deeply appreciated reading and learning more about Angelou’s amazing life, which I hadn’t realised the book was so closely based on.

Growing up in the UK I was never ‘forced’ to read American classic The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, but I did so under my own free will this year and enjoyed it once the action picked up. The Passion of New Eve was a blast of Angela Carter: violent and sexual and liable to fuel the flames depending on how you see it. My mum suggested The Post-Office Girl, full of vivid descriptions of places and characters, and by the end I was quite keen to see whether the heroes would be able to pull off their crime or not. Exit West is a (somewhat obvious) metaphor for the era of global migration we are living through, but I actually found the birth and death of a relationship to be the most moving part. Finally, All The Light We Cannot See was a beautifully written and fast-paced intertwined story of a blind French girl and a German boy during World War Two. It made me sad about Brexit all over again.

Non-Fiction

The only American history I ever studied was all post-Civil War, and so I found American Nations to be incredibly helpful in understanding how the United States was first put together. I had no idea that the slave system of the Deep South migrated from Barbados, for example, or the sharp distinctions between the New England Puritans and the Virginian gentry which can be traced back to the English Civil War. Meanwhile, it is easy to forget the Spanish settlements in Florida and New Mexico which get lost in all of the ‘East to West’ narrative. I am sure you can quibble with exactly how Woodard carves up the country, but overall I have a much better grasp of its distinct cultures and histories.

Jumping forward in time to Lincoln, Team of Rivals – which took me a month to get through – is a very detailed account of his rise to the Presidency together with his leading competitors. It was well worth reading although I was expecting a little more historiography along with the narrative, and I still have some unanswered questions. For example, was Lincoln actually any good as a war leader? The Civil War certainly reads like a series of military disasters in the beginning, although perhaps the whole government would have disintegrated under anyone else.

Rounding out the American history, I also read The End of Inequality, a click-bait title for what is actually a fairly dry piece of academia on the (genuinely fascinating) 1962 Baker vs. Carr decision. Save yourself some time and listen to the More Perfect episode instead. I am also down on this book because in the last few pages they become fabulously stupid and wrong about international solutions to gerrymandering.

If you want a chillingly relevant insight into the ‘anti-politics’ mood, They Thought They Were Free is based on interviews with ten ordinary Nazis from a quiet, non-industrial German town conducted right after the Second World War. Similarly, not because they are Nazis but for a a comparable bottom-up perspective of the modern American right, I highly recommend Strangers In Their Own Land. Arlie Hochschild, a sociologist from Berkeley, does an excellent job talking to conservative voters from rural Louisiana, and smartly uses the issue of local environmental damage (from which these people suffer a great deal) to probe the question of why they continue to oppose any government protection or regulation.

Finally, if you want to panic about a different social nightmare, read The Gene by Siddhartha Mukherjee. As with his previous book on cancer, The Emperor Of All Maladies, this is a fascinating and informative exploration of the history and science of genetics. But I came away with a terrible sinking feeling about where genetic engineering is going to lead us. Alternative, there’s always the equally dark world of Plato’s The Laws, in which Plato (a) sneakily tries to make his own book compulsory reading material, (b) bans discounting (thanks, dude) and (c) limits his city’s population to 5040 citizens exactly. Good luck with that.

I am really, really pleased with the books I read in 2016. And I tried to get better about making some quick notes as I did so… partly to remember more, and partly to make writing this review easier at the end. Let’s see how well I did!

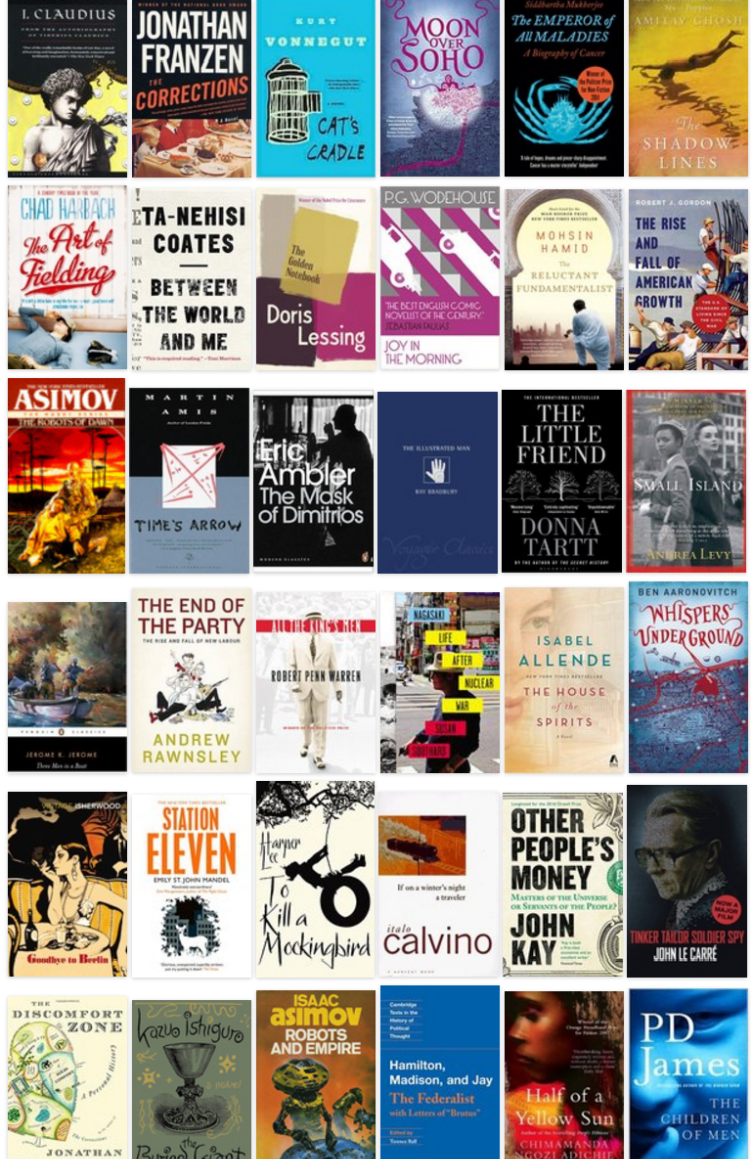

My first book was I, Claudius, an incredibly bloody underdog story gifted by Todd. (Spoiler alert: just about everybody is murdered by the end.) Other Todd-influenced reads this year included The Corrections, an absorbing family drama and ‘state of the nation’ book, and The Art of Fielding which left me forever fearful of getting struck in the face with a baseball. It’s an interesting story because every single character is basically good and well-intentioned, yet everything falls apart anyway.

I also had high hopes for The Little Friend but found it much less cohesive than last year’s The Secret History. That said, many of its scenes and characters have remained vivid in my memory – Hely trapped in the apartment with the snakes, for example – and my research for this post suggests the murder-mystery aspect isn’t left quite as unresolved as I had thought. The main character, Harriet, has an obvious forerunner in To Kill a Mockingbird‘s Scout: a classic child’s-eye perspective which I finally read this year.

I really loved reading Asmiov’s Robot series, more so each time, which I concluded this year with Robots of Dawn and then Robots and Empire. Not only was the latter a well-timed piece of post-Trump escapism, but it also serves as Asimov’s bridge between previously distinct series, and I am eager to keep going next year. It also took some effort to limit myself to reading two of Ben Aaronovitch’s moreish Peter Grant series (Moon Over Soho and Whispers Under Ground). It’s hard not to love something infused with so much London. The Illustrated Man was another collection of Ray Bradbury’s wonderful (and mostly creepy) short stories, tied together with an unsettling framing device.

After a weaker Ishiguro last year, The Buried Giant was one of my favourite books of 2016. Following the journey of two elderly Britons, Axl and Beatrice, the book is set in post-Arthurian Britain (a time period I rarely think about) in which memory is mysteriously suppressed and an uneasy peace holds between Britons and Saxons. Its opening was so intriguing and the book held me rapt throughout. For fans of Ishiguro’s style, this is highly recommended. And on subject of Ishiguro, The Reluctant Fundamentalist is aptly compared to The Remains of the Day for its gripping first-person narrative style which drives it towards a suspenseful thriller of an ending.

Another of my favourites this year was Station Eleven, a good old-fashioned post-apocalyptic dystopia (plus travelling Shakespeare troupe) which I raced through. Cat’s Cradle was a much better Vonnegut than my last attempt, and the concept of a granfalloon actually occurs to me a lot now. Time’s Arrow, a novel in which a Nazi doctor’s life runs in reverse, will mess with your head and convince you that real life is also running backwards. And I was initially very into the postmodern If on a winter’s night a traveller although there is something undeniably frustrating about a succession of cliffhangers from different imaginary books, even if the ending comes with a nice ‘a-ha!’ moment.

I feared getting lost in the magical-realist epic The House of the Spirits but was kept engaged by the intertwining of real Chilean history, which I really appreciated learning more about. Similarly, I learnt about Biafra and the Nigerian Civil War in the 1960s through Half of a Yellow Sun, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s engaging but slowly devastating book about the conflict. All the King’s Men wasn’t quite my style, but is apparently modelled closely on an interesting figure in Louisiana political history. (Oh, for the days when a populist American demagogue would at least build some hospitals.)

Turning to non-fiction, The Emperor of All Maladies – billed as a ‘biography of cancer’ – taught me so much about a vast subject which I had never really considered before. Perhaps the most important lesson is how unstraightforward medical ‘progress’ is. You might imagine that the history of cancer treatment is one of slow, incremental improvement… but it’s just much more complicated than that, with many intellectual dead-ends and ‘breakthroughs’ which come with horrible trade-offs. And yes, I did read some of this on a beach.

Prompted by Brexit, it felt like the right time to revisit the New Labour era in Andrew Rawnsley’s gossipy The End of the Party which documents the full destructive force of the Blair-Brown relationship. It seems like such a long time ago now. The Rise and Fall of American Growth was a much drier read, as you might expect from economic history, but it makes one side of an important argument about the uniqueness of the twentieth century. It also led to me boring people at work for weeks with random factoids, for which you can blame ‘The Weeds’ podcast for recommending it in the first place. One annoying spot in a generally magisterial work, albeit sadly common to many discussions, is the breezy assumption of ‘more marriage’ as a social good with no real nuance or consideration.

It was also good timing to read The Federalist (with the opposing Letters of Brutus, which makes some prescient predictions about the Supreme Court) straight after the election, at the very moment when Hamilton’s Electoral College defence started popping up all over Facebook. The Papers were written to urge adoption of the newly written US Constitution and defend it from accusations that too much power was being centralised, which puts me in a weird position as someone who looks at two-year terms in the House of Representatives, for example, and thinks ‘that’s absurdly short’ as opposed to ‘that’s long enough for tyranny to strangle the liberty of the people’. So I guess it made me more sympathetic to the Constitution (never my favourite document) as an achievement over nothing at all.

But a more important perspective on these events can be found in Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me, a series of letters to his teenage son about the history of race in America and what it means for him. This is somewhat difficult to write about, given that only yesterday I heard Coates speaking about his frustration that the unexpected popularity of the book amongst white liberals ends up hurting his ability to write and think and explore freely. And we need that. So I will limit myself to the two most memorable things which I took from this book, which you should read. One is the moral clarity that people in the past “didn’t ask to be your martyrs”: pain and suffering by some cannot be ‘made good’ to others. The other, more personal, is his description of an incident with his five year-old son on an escalator. It is one of the most powerful things I have ever read.

Rounding off the non-fiction was Other People’s Money (a persuasive reminder that we have far more financial activity than we need) and Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War. Susan Southard’s account of the 1945 atomic bombing, and the lives of its survivors, was at times so horrific that I had to stop reading it on a plane for fear of passing out. But it is a worthy discussions of events which are usually discussed in the abstract.