I am really, really pleased with the books I read in 2016. And I tried to get better about making some quick notes as I did so… partly to remember more, and partly to make writing this review easier at the end. Let’s see how well I did!

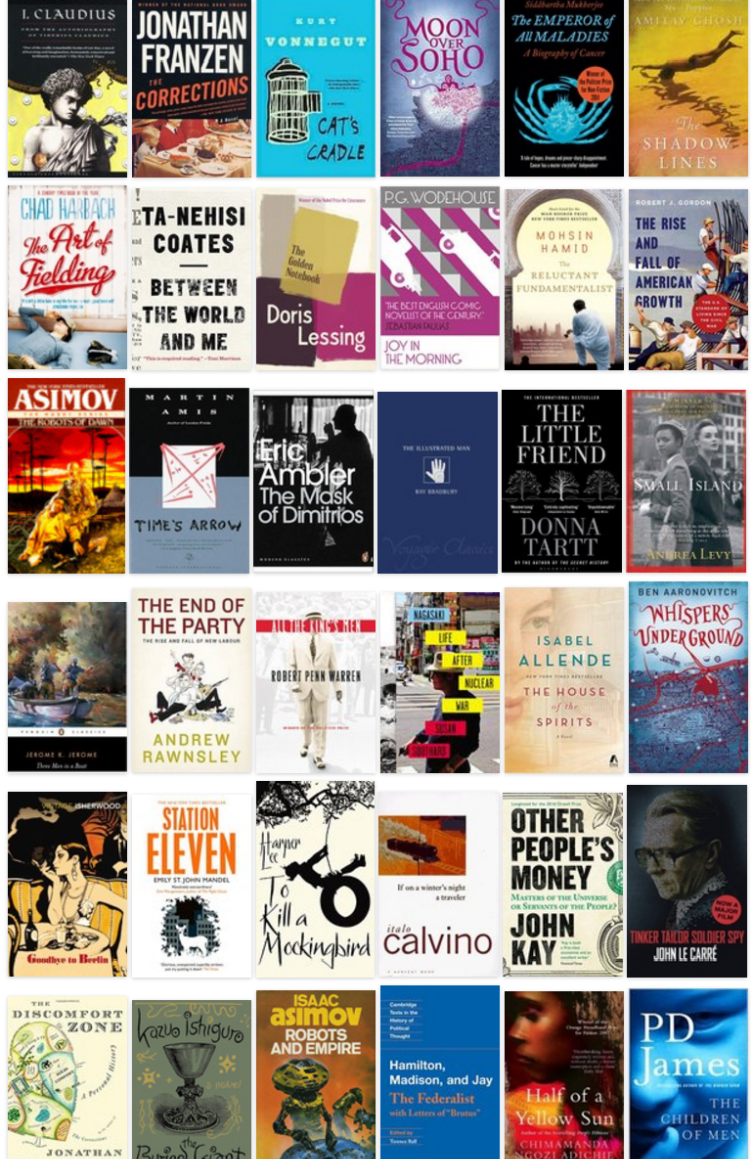

My first book was I, Claudius, an incredibly bloody underdog story gifted by Todd. (Spoiler alert: just about everybody is murdered by the end.) Other Todd-influenced reads this year included The Corrections, an absorbing family drama and ‘state of the nation’ book, and The Art of Fielding which left me forever fearful of getting struck in the face with a baseball. It’s an interesting story because every single character is basically good and well-intentioned, yet everything falls apart anyway.

I also had high hopes for The Little Friend but found it much less cohesive than last year’s The Secret History. That said, many of its scenes and characters have remained vivid in my memory – Hely trapped in the apartment with the snakes, for example – and my research for this post suggests the murder-mystery aspect isn’t left quite as unresolved as I had thought. The main character, Harriet, has an obvious forerunner in To Kill a Mockingbird‘s Scout: a classic child’s-eye perspective which I finally read this year.

I really loved reading Asmiov’s Robot series, more so each time, which I concluded this year with Robots of Dawn and then Robots and Empire. Not only was the latter a well-timed piece of post-Trump escapism, but it also serves as Asimov’s bridge between previously distinct series, and I am eager to keep going next year. It also took some effort to limit myself to reading two of Ben Aaronovitch’s moreish Peter Grant series (Moon Over Soho and Whispers Under Ground). It’s hard not to love something infused with so much London. The Illustrated Man was another collection of Ray Bradbury’s wonderful (and mostly creepy) short stories, tied together with an unsettling framing device.

After a weaker Ishiguro last year, The Buried Giant was one of my favourite books of 2016. Following the journey of two elderly Britons, Axl and Beatrice, the book is set in post-Arthurian Britain (a time period I rarely think about) in which memory is mysteriously suppressed and an uneasy peace holds between Britons and Saxons. Its opening was so intriguing and the book held me rapt throughout. For fans of Ishiguro’s style, this is highly recommended. And on subject of Ishiguro, The Reluctant Fundamentalist is aptly compared to The Remains of the Day for its gripping first-person narrative style which drives it towards a suspenseful thriller of an ending.

Another of my favourites this year was Station Eleven, a good old-fashioned post-apocalyptic dystopia (plus travelling Shakespeare troupe) which I raced through. Cat’s Cradle was a much better Vonnegut than my last attempt, and the concept of a granfalloon actually occurs to me a lot now. Time’s Arrow, a novel in which a Nazi doctor’s life runs in reverse, will mess with your head and convince you that real life is also running backwards. And I was initially very into the postmodern If on a winter’s night a traveller although there is something undeniably frustrating about a succession of cliffhangers from different imaginary books, even if the ending comes with a nice ‘a-ha!’ moment.

I feared getting lost in the magical-realist epic The House of the Spirits but was kept engaged by the intertwining of real Chilean history, which I really appreciated learning more about. Similarly, I learnt about Biafra and the Nigerian Civil War in the 1960s through Half of a Yellow Sun, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s engaging but slowly devastating book about the conflict. All the King’s Men wasn’t quite my style, but is apparently modelled closely on an interesting figure in Louisiana political history. (Oh, for the days when a populist American demagogue would at least build some hospitals.)

Turning to non-fiction, The Emperor of All Maladies – billed as a ‘biography of cancer’ – taught me so much about a vast subject which I had never really considered before. Perhaps the most important lesson is how unstraightforward medical ‘progress’ is. You might imagine that the history of cancer treatment is one of slow, incremental improvement… but it’s just much more complicated than that, with many intellectual dead-ends and ‘breakthroughs’ which come with horrible trade-offs. And yes, I did read some of this on a beach.

Prompted by Brexit, it felt like the right time to revisit the New Labour era in Andrew Rawnsley’s gossipy The End of the Party which documents the full destructive force of the Blair-Brown relationship. It seems like such a long time ago now. The Rise and Fall of American Growth was a much drier read, as you might expect from economic history, but it makes one side of an important argument about the uniqueness of the twentieth century. It also led to me boring people at work for weeks with random factoids, for which you can blame ‘The Weeds’ podcast for recommending it in the first place. One annoying spot in a generally magisterial work, albeit sadly common to many discussions, is the breezy assumption of ‘more marriage’ as a social good with no real nuance or consideration.

It was also good timing to read The Federalist (with the opposing Letters of Brutus, which makes some prescient predictions about the Supreme Court) straight after the election, at the very moment when Hamilton’s Electoral College defence started popping up all over Facebook. The Papers were written to urge adoption of the newly written US Constitution and defend it from accusations that too much power was being centralised, which puts me in a weird position as someone who looks at two-year terms in the House of Representatives, for example, and thinks ‘that’s absurdly short’ as opposed to ‘that’s long enough for tyranny to strangle the liberty of the people’. So I guess it made me more sympathetic to the Constitution (never my favourite document) as an achievement over nothing at all.

But a more important perspective on these events can be found in Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me, a series of letters to his teenage son about the history of race in America and what it means for him. This is somewhat difficult to write about, given that only yesterday I heard Coates speaking about his frustration that the unexpected popularity of the book amongst white liberals ends up hurting his ability to write and think and explore freely. And we need that. So I will limit myself to the two most memorable things which I took from this book, which you should read. One is the moral clarity that people in the past “didn’t ask to be your martyrs”: pain and suffering by some cannot be ‘made good’ to others. The other, more personal, is his description of an incident with his five year-old son on an escalator. It is one of the most powerful things I have ever read.

Rounding off the non-fiction was Other People’s Money (a persuasive reminder that we have far more financial activity than we need) and Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War. Susan Southard’s account of the 1945 atomic bombing, and the lives of its survivors, was at times so horrific that I had to stop reading it on a plane for fear of passing out. But it is a worthy discussions of events which are usually discussed in the abstract.

Andy Regan, Stephanie Francesca Pereira, Chloe Booth, Natasha Self, Gillian Self, Sharon Dinkin, Katie Sharing liked this post.

Aah I’ve just ordered the Ta-Nehisi Coates, excited now

Sarah got the Ta-Nehisi Coates book for Christmas. I shall read it after her. Thanks for this list, Dominic. Interesting insight into all the works discussed here – and into what you have been up to this past year.