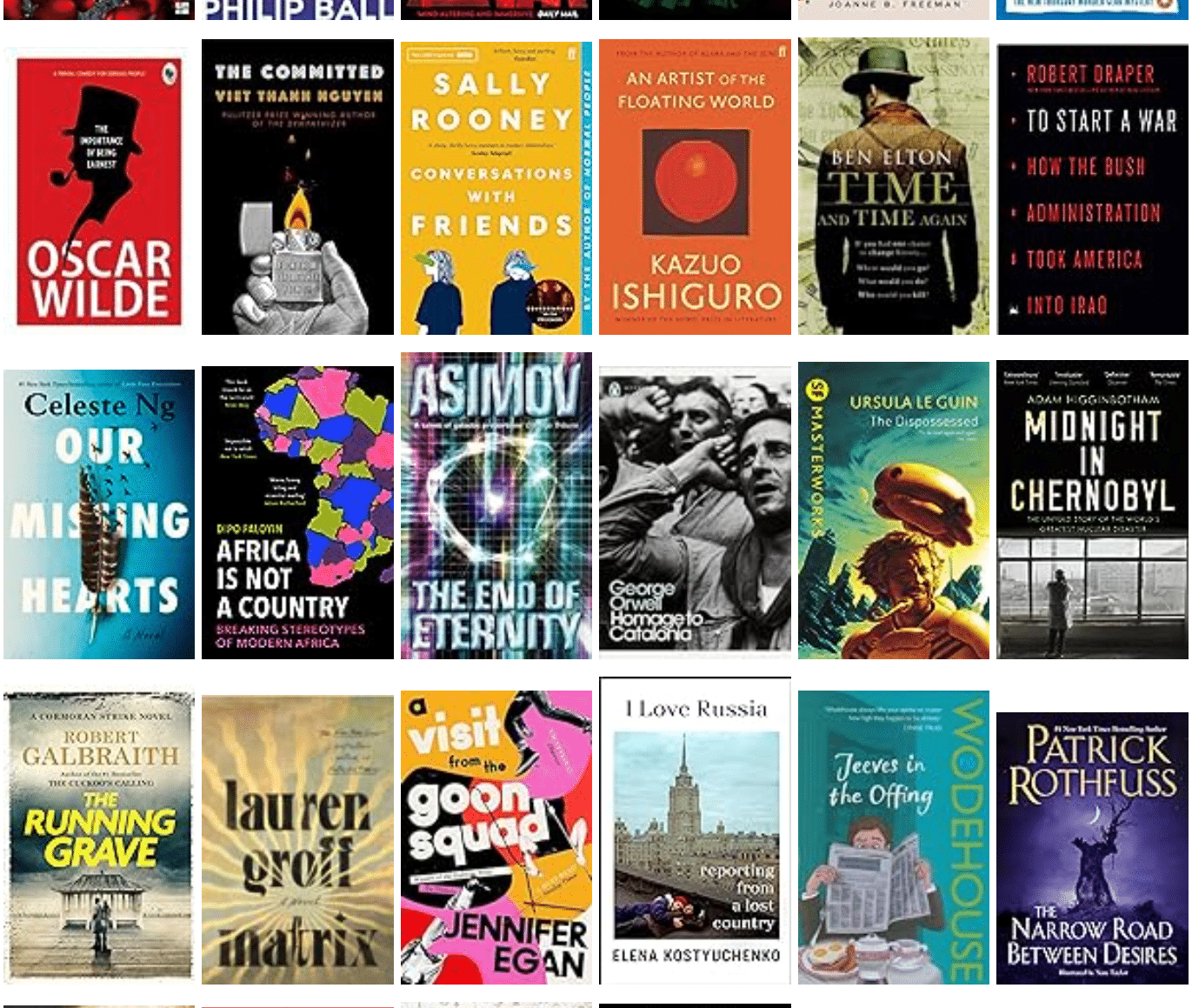

Once again, it’s time for my annual reading review, i.e. the moment when declining to rate any books on Goodreads is finally rectified. It hasn’t been a peak reading year, to be honest, with a lowly total book count of 28 (my lowest since 2014) and a failure to find that one standout story which really whisked me off my feet and took me somewhere dazzlingly, thrillingly new. Nevertheless there are a lot of good, solid entries below, with lots to recommend if you’re making your own plans for 2024.

Fiction

I’m usually pretty good at picking my first book of the year, but ended up with very mixed feelings about Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. It’s definitely a novel I’m ‘supposed’ to like, but it took me over a month to slog through it and with such a large cast of characters it’s irritating to deal with the unnecessarily added complexity of having to puzzle out exactly who is speaking (which is often unclear). That said, it’s also the kind of book which improves on reflection and, after reading some helpful reviews, I came to appreciate this portrayal of Thomas Cromwell – a self-made, wry, pragmatic rationalist – as some kind of anachronistic emissary from modernity. Mantel is also very good at conveying the human drama of Tudor politics, particularly in the scenes with a humiliated, angry young Mary.

One of my honeymoon reads was Death’s End, the final entry in Liu Cixin’s Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy. It’s a brilliant series, of immense scope, and the third book continues to explore complex science fiction concepts over many future eras of humanity, including a memorable section featuring three densely metaphorical fairy tales which continue to haunt me. In fact, there’s an inescapable melancholy to a lot of this trilogy – difficult to avoid when you’re dealing with the end of the universe, I guess – so if you’re looking for an uplifting location to read the very last page, I can heartily recommend (from personal experience) that a heated pool overlooking the magnificent forests of Guatapé, Colombia will do the trick.

Another (quite different) honeymoon read was The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo, by Taylor Jenkins Reid. This is a highly enjoyable, fast-moving page turner with an intriguing set-up: former Hollywood star Evelyn Hugo, now a recluse, handpicks a young, inexperienced journalist to spill her life’s secrets to. But why her? Spoiler: there is a shock ending, which is all part of the fun even though it feels awfully contrived. There is no shock ending to Woman at Point Zero – a very different kind of book – first published in Arabic by Nawal El Saadawi in 1977. But it’s written with bracing clarity and can be read as a gripping page turner of its own, even though you know from the very beginning exactly what will happen to Firdaus. Based on a real person, she is female prisoner condemned to death for murdering her pimp who nevertheless retains her own fierce dignity as she tells her life story.

I was not overly impressed by The Committed, a sequel to Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer. A thriller is supposed to have some thrills, but everything is weighed down by a lot of laboured intellectualism and compared to the original book it left me cold. On the contrary, A Visit from the Goon Squad is the Jennifer Egan book which I should have read last year when I plumped for Manhattan Beach, and I’m grateful for Todd and Carolyn’s quizzical raised eyebrows in convincing me to go back and try this one out instead. I enjoyed this a lot more, even though the punk rock / music industry setting was not initially appealing, and I appreciated the unusual interlinked short-story structure to the book once I understood that’s what was happening and I wasn’t just struggling to keep track. Also, as soon as I finished I immediately thought that it would be really useful if somebody had made a diagram of how all of the characters and storylines intersect, so kudos to the many people on the internet (here’s a good one!) who have of course already done that.

Confession time: I don’t think I will ever be the right target audience for Lauren Groff’s Matrix. I did try! In fact, the omens were good when I started on the intriguing first chapter, curled up on a comfy chair in the top floor of Chicago’s Open Books bookshop. What’s this? Lauren Groff’s new book is set in a 12th century English abbey? But try as I might, this study of intense religious mysticism and slow-burning sexuality was never going to make my list of favourites, even though I can recognise it as objectively good writing. To embarrass myself further, I even paused reading it halfway through to binge on the newly-released Comoran Strike instalment, which is a bit like sneaking out of the back of a high-end Chicago restaurant to go eat at Chick-fil-A. But, man, it was good.

The Running Grave is easily categorised as ‘the one where Robin infiltrates a cult’, which (a) keeps the tension very high throughout, (b) is a good strategy to plausibly prolong the Strike/Robin relationship, (c) is occasionally tiring and you wish she would just get out sooner. Less so than the last book, but I still found the ending a bit of a problem: everything seems to collapse and resolve itself more quickly than you’d expect, and there’s no big showdown with the cult leaders. Of course, all of this is quickly forgotten with the big cliffhanger ending… which I do fear will be easily glossed over again at the start of the next book. We shall see.

I do understand and respect those who no longer wish to read JK Rowling. For me, the most extreme example this year where the personal failings of the author really intruded onto the work itself came when reading Isaac Asimov’s The End of Eternity. Asimov’s sexism shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone who’s read his books (although the extent of his personal criminality is awful) but in this story his refusal/inability to write a realistic female character in Noÿs Lambent really undermines a promising sci-fi concept. Anyway, this book is the story of the ‘Eternals’, an elite, arrogant organisation who meddle in humanity’s timeline and, intriguing, also facilitate commercial trading between different eras. So, think of the ‘Observers’ from Fringe with a little dash of the WTO thrown in for good measure. Despite the character flaws, I appreciated the Cold War-era vibes (this is definitely a critique of central planning, amongst other things) and the philosophical charge of the book’s final line.

For a more sophisticated imaginings about politics under the guise of science-fiction, try Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed from 1974. Anarres is a moon orbiting the planet Urras. Resources are scarce, but society is successfully organised under an anarcho-syndicalist model after being founded by a one-off set of idealistic colonists from Urras several centuries earlier. I do believe there is a strong case for authors to write utopias – not just the more common dystopias – and this classic of the genre is a very credible attempt to explore a somewhat-believable anarchist utopia. Guin does a superb job at balancing a genuinely attractive form of communism with the reality of how utterly crushing it would likely feel if you were not brought up in it, and I think the interwoven nature of politics and culture is the real point of this book. The relationship between Anarres and Urras also made sense to me, and the language and worldbuilding is top class: the ‘dispossessed’ of the book’s title are poor but also reject possessions, unlike the ‘propertarians’ of Urras. The plot itself, as so often in these types of books, is less compelling.

In contrast to Le Guin, Celeste Ng’s Our Missing Hearts is a much more ‘standard dystopia’ and I found it a little rote. Don’t get me wrong, it’s well-written and a perfectly compelling read, but the implementation of PACT (Preserving of American Cultures and Traditions Act) felt cartoonish and contrary to everything we know about how American society actually works. In this novel, the US is rapidly transformed (by ‘The Crisis’) into a deeply repressive, authoritarian state with virulent racism directed against Asians. My issue is obviously not that there isn’t a lot of racism against Asian Americans already (of course there is), nor that a society couldn’t transform at frightening speed (of course it could) and, of course, everybody knows the American state has form when it comes to enforcing racism through terror. I just didn’t buy this telling of it. American society is so noisy and fragmented that a clean, wholesale transition to this New Order is too unsubtle, too straightforward, and not hypocritical enough. That said, and maybe this sounds contradictory, I did really enjoy reading it. So please read it too, and then we’ll see if I’m the only one who feels this way.

The Man Who Died Twice – the second in Richard Osman’s Thursday Murder Club series – is a fun read, but I do think his instinct that all his characters are so arch and ironic all the time ends up undermining the individual characterisations. It also removes jeopardy when everyone manages to be suave and unruffled in the face of all threats. Well, I say that, but most characters remained pretty unruffled in Agatha Christie’s cracking The Body in the Library and it was still excellent. I also chuckled to myself at her insertion of a character praising Agatha Christie as one of the great crime authors of the day… so maybe I should just fully accept the Thursday Murder Club books on the the same cosy terms.

Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends was very enjoyable. To steal brazenly from another review, her characters “zig where you’d expect them to zag” and I found that to be very true: there’s something about her writing which sends these relatable human moments into unexpected directions. This year I also went back to Ishiguro (but I really am running out now) for An Artist of the Floating World, which is set in post-war Japan and centred on an elderly painter whose former reputation is now tarnished by his actions during the war. This is exactly what you’d expect from Ishiguro and nothing less: unreliable narration and memories mingled with guilt, denial and misdirection about the past.

By challenging all of my skills of emotional repression, I have successfully subsumed any desire to read the third in Patrick Rothfuss’s Kingkiller Chronicles trilogy into a Schrödinger’s box of anticipation: it won’t be there until I look. In that spirt, I enjoyed his yet-another-diversionary novella, The Narrow Road Between Desires, as an evocative ride through a day in the life of Bast. It helped that I hadn’t read the short story of which this is a slightly-longer revamp. Talking of novellas, this year my Rivers of London diet was limited to the new Winter’s Gifts sidequest featuring FBI Special Agent Kimberley Reynolds. This was fun (giant tentacles emerging from the ice!), but let’s be honest and agree that Kimberley is a weird mishmash of American stereotypes which don’t quite come together as a convincing person. Oh, and on New Year’s Eve I snacked on Philip Pullman’s The Collectors, a spooky short story from the worlds of His Dark Materials with little hints about the early life of Mrs Coulter.

Finally, I had a lot of fun with Ben Elton’s Time and Time Again, and am still impressed by the little twist in our assumptions about the timeline which is revealed near the end. To summarise the conceit: a secret society of Cambridge academics, with a nostalgic yearning for the lost greatness of European society destroyed by WW1, find a way to send ex-solider Hugh Stanton back in time to prevent the assassination of Franz Ferdinand and then, for good murder, kill the Kaiser. Spoiler: this is not a good plan. One slight issue I have with this book is that I think Ben Elton wants to skewer the ‘Great Man of History’ school of history in favour of wider social and economic forces, but then his actual plot ends up making the ‘wider social and economic forces’ brigade look like a bunch of idiots since minor historical changes (again, spoiler alert) end up having utterly massive implications. So the real lesson ends up being ‘obviously you can’t just fix the twentieth century by shooting the German Emperor in the head’, which I think we knew already. But who cares? It’s super fun and I want a turn with the time-travel history-messing toy now.

Oh, and one evening – inspired by Angela downstairs, I think! – Randi and I decided to read The Importance of Being Earnest out loud as a piece of old-fashioned entertainment. I enjoyed this, and we should do it again, but next time we should either pick a two-handed or rope some other people into joining us so we don’t have quite so many characters to cover…

Non-Fiction

Beyond Weird was my first non-fiction book of 2023, and in my mind is indelibly linked to the physical sensation of reading it from a hammock on the front porch of our homestay in Colombia, after the sun went down, on the first night of our trek. For a funk-inducing guide to quantum physics and the deep mysteries of nature, this felt very appropriate. Quantum physics is a common subject for popular science books – precisely because it’s so weird and counterintuitive – and although this book strives to move beyond the clichés (hence the title!) there’s still something shocking about, say, the double split experiment – no matter how many times you’ve read it before. Anyway, this was a great book and highly recommended whether you’re new to this world or not.

Joanne B. Freeman’s The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War is one of those books which I picked up as a recommendation from The Ezra Klein Show years ago and finally got around to reading this year. It’s also one of the most ‘history’ history books I’ve read in a while: sticking to a carefully defined domain (physical violence in the US Congress during the antebellum years) and inspired by a close reading of a primary source (the diaries of Benjamin Brown French, a clerk in the House of Representatives). French himself is an interesting figure precisely because he himself is historically insignificant and largely goes with the flow, starting off by seeing the abolitionists as a radical, disruptive influence and then slowly shifting as the political realities shift around him. These type of people are, of course, much more common than the few unusual characters who usually make it into popular political histories.

Anyway, my main takeaway from this book – and this may not shock anyone – is that it doesn’t actually seem that Congress itself was inherently violent, at least for the time, but rather that the representatives of the South in Congress were unusually and exceptionally violent! Given that they were representatives from a monstrous society based on plantation chattel slavery this doesn’t seem all that surprising, but I think it’s worth pointing out since it reminds me of the equally absurd equivalences drawn between Democrats and Republicans in Congress today. Whatever you think of them, they really aren’t just neatly symmetrical mirror images of each other.

Skipping forward to much later American politics, Robert Draper’s To Start a War: How the Bush Administration Took America into Iraq is, well, exactly what the subtitle says it is. This is very much a personal story of individual decision-making and organisational politics gone wrong rather than a big-picture geopolitical account. As a result, some of the most interesting parts (at least to me) are those things which might have broader lessons for organisational culture. For example, I was intrigued by Bush’s management style: he wanted brisk, efficient meetings where the people under him presented a consensus view which they had already hashed out between themselves. In the context of the Iraq War, this seems obviously dangerous, as it was far too easy for complications, caveats and opposing views to be squashed before ever coming close to the President. Then again, I can easily imagine the opposite style being critiqued elsewhere for its meddlesome micromanagement! (Sigh… this indecision is why I’m not destinated to write the next bestselling airport book for aspiring middle managers.)

I bought Africa Is Not a Country in a bit of a bookshop panic: that feeling when you’re overwhelmed by choice, overwhelmed by all of the books on your to-read list already and just want to take a punt on something unexpected. It paid off, because this collection of essays by Dipo Faloyin was an absorbing read, covering topics from the profoundly negative legacy of nineteenth-century European borders in to today’s intensely competitive West African rivalry over how to make the perfect jollof rice. His wider point, which is not new but always worth making, is to push back against very harmful and totalising narratives of the entire African continent. Of course, the only way to do that successfully is to familiarise more readers with specific people and places.

As a meta-point: Faloyin’s background is as a senior editor at VICE and you can really tell that he grew up writing for online audiences. I wish more non-fiction book authors would embrace the flexibility which results from this style. The chapters in this book vary dramatically in both tone and length, with no attempt to enforce an unnecessary consistency. If the chapter is done, it’s just done.

I laugh at myself when it comes to Homage to Catalonia, which is (of course) George Orwell’s first-hand account of his time spent as a volunteer fighter in the Spanish Civil War. Famously, this doesn’t include an awful lot of fighting, and Orwell successfully captures the sense of boredom, frustration and futility which pervades the conflict. In the original edition, Orwell includes two ‘background’ chapters about the wider political situation and the internecine feuds between the Communists backed by the USSR and Trotskyist groups such as POUM, which is the group that Orwell himself had joined. Later, Orwell requested that these chapters be moved to become two appendices at the very end of the book, and apologetically notes that future readers may find them outdated and uninteresting. Most modern Goodreads reviews seem to agree, but for me these were by far the most interesting part of the book! I’ll take obscure political manoeuvrings over a description of what it’s like to get shot in the neck (spoiler: unpleasant) any day.

I hadn’t seen any TV series or film about the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, so Adam Higginbotham’s Midnight in Chernobyl: The Untold Story of the World’s Greatest Nuclear Disaster had the advantage of giving me all the facts and characters afresh. It’s a totally compelling thriller with so many sad and shocking stories, especially when a piece of personal heroism or self-sacrifice turns out to have been completely pointless. The moment which stuck with me most vividly came soon after the explosion when three engineers are investigating the state of the reactor, pass through an airlock, stare right into the core of the reactor and – within seconds – are suddenly exposed to utterly fatal doses of radiation. Worse, at least one of them is a veteran of nuclear submarines and immediately understands that he is now doomed to die, and soon. It’s chilling.

As a veteran listener of Tim Harford’s Cautionary Tales podcast, the immediate cause of the accident is also so familiar. A series of small mistakes, bad decisions and the understandable desire to just get a routine late-running test over and done with: all things which, on their own, wouldn’t have amounted to anything but just so happened to come together that night in the most awful way possible.

Finally, a massive thanks to Kira for gifting me I Love Russia: Reporting from a Lost Country. This is a collection of journalism by Elena Kostyuchenko, a Russian reporter for the Novaya Gazeta newspaper who is now barred from returning to her home country after covering the war in Ukraine. In the book, short autobiographical segments are used to preface much longer essays from her career, covering everything from squatters living in Moscow’s huge, abandoned and very creepy Hovrinskaya Hospital (since demolished) to a community of sex workers working overnight by the side of a highway and her own brutal experiences of attending Gay Pride marches in Russia. A very moving collection.