After a dip in 2014, this year I returned to my upward curve for number of books read. And yes, while caring about the raw number is silly, it’s also a good motivator to do something I really enjoy but otherwise struggle to make time for. And I read some great things in 2015…

I’ve seen plenty of interesting authors interviewed about their books on The Daily Show over the years, but I rarely manage to follow-up by reading them. Something about Bryan Stevenson was compelling enough to buck this trend, and his account of working as a lawyer to overturn horrendous miscarriages of justice in the American South – Just Mercy – was one of the most powerful and important things I read this year. It’s about a whole lot more than the death penalty, but the image of a prison officer strapping a defenceless human being into a chair and executing him – at the behest of the state – is one of the most jarring and frightening intrusions of barbarism into the modern world I can imagine. I think there is validity to the argument that we over-praise democracy and under-appreciate the rule of law, and in a world where entirely innocent people can be arrested, convicted, imprisoned and killed, both are denied.

Another Daily Show recommendation was The Underground Girls of Kabul, which tells the fascinating story of bacha posh: girls raised as boys, at least until adolescence, for both ‘luck’ and raw practicality in cultures where being born female is so bad it can make your mother weep. A useful reminder both of the constructed nature of gender, and the hidden adaptations and compromises which ‘real people’ always make below the surface of a society. Another book about being born in the wrong place at the wrong time was the classic There Are No Children Here (a gift from Robert) which follows two young boys growing up in Chicago’s prison of poverty and violence. It’s really not far away. And in turn, Educational Failure and White Working Class Children in Britain (Tash’s recommendation from years ago) well articulates social class in Britain, which can be hard to explain to people here.

On a more upbeat note, Rivers of London – recommended by Diamond Geezer a few times on his blog – was a rough but promising Gaiman-esque urban fantasy, and sets up an intriguing series to follow. Ready Player One was even more fun: a page-turning young adult adventure which appealed to someone with only conversational fluency in 1980s pop culture. It certainly left me more uplifted than the similar Ender’s Game, which others feel passionately about, and is a good read but also surprisingly chilling and sad. I am a little intrigued to see what happens next, but I won’t be rushing. It’s the same story with Mask of the Verdoy, which attempts to kick off a series of 1930s London detective stories, but wears its amateur historian heart a little too closely on its sleeve. (Please don’t put dialogue into Ramsay MacDonald’s mouth unless you really know what you’re dong.)

A few books were return visits to worlds from previous years. I’ve loved all of JK Rowling’s Cormoran Strike series, but the third entry – Career of Evil – improved on its predecessors with a satisfying ending to the murder plot as well as the usual enjoyment of being among Robin and Strike. In the same vein, I very much enjoyed Agatha Christie’s fiendishly clever ending to The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Something Fresh was my first non-Jeeves PG Wodehouse book, and while it didn’t make me laugh quite as much, I will certainly be back for more. Asimov’s The Naked Sun, the second in his Robot series, was better than the first and sketched a memorable portrait of an elite society with a crippling phobia of human contact. My other classic sci-fi of the year, Ray Bradbury’s collection of short interlinked stories The Martian Chronicles (thanks, Katie!), was also wonderfully alien and spooky. I’ll be back for more of him, too.

I had put off reading Dracula for years, but it was surprisingly fluid and gripping, at least for most of the way through. The much-discussed ‘undertones’ of Victorian sexual fears are not so much undertones as raw panic – at one point sweet, wholesome Mina is forced to her knees to suck Dracula’s blood out from his chest while her humiliated husband lies unconscious – but you didn’t expect today’s mores from the granddaddy of nineteenth century Gothic horror, did you? At least Mina has a pretty happy relationship when she’s not being drained to death. The experience of Dorothea in Middlemarch, by contrast, is a sad reminder of the Victorian ‘cross your fingers and hope for the best’ approach to marriage for women. I was more enthralled than I expected to be by George Eliot’s long but well-paced classic on provincial life. And then every so often I would pause to give sincere thanks for dating and contraception.

This year I also got around to Crime and Punishment. No doubt Dostoevsky is masterful at getting under the skin of his jumpy and degenerating protagonist, Raskolnikov, but he also hits you in the face with Christian salvation a little too much for my liking. And most of said salvation is delivered by poor Sonya, who becomes inexplicably devoted to her best friend’s murderer. (She’s a prostitute, so her devotion to others is supposed to act as her own redemption, except today it’s hard to conjure up any feelings of condemnation and so she becomes purely a martyr.)

Two American novels which Robert and Todd both suggested – Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom and Donna Tartt’s The Secret History – were both great. The Secret History is the greater of the two, I think, mostly because I was successfully ensnared into mentally egging on the murder before being dumped with real feelings of horror and guilt afterwards. Freedom has become hazier in my mind over the year, although I do remember thinking it shared a literary style with Zadie Smith. And Pastoralia, George Saunders’s collection of brisk (and often weird) short stories satirising modern life, was another recommendation (thanks, Katie Schuering!) I will gladly pass on to others. Gertrude Stein’s Paris France was also odd but breezy: like going to lunch at a café with an eccentric aunt, whose observations on life are mostly ludicrous but pleasant enough to listen to for a bit. On the other hand, The Fortress of Solitude – a Brooklyn-based coming-of-age story – was more of a slog.

In the late nineteenth century, in Chicago, Herman Webster Mudgett built a hotel to host visitors to the Chicago World’s Fair. The ‘castle’ took up an entire block and was designed to be as confusing as possible: a maze of rooms at odd angles with staircases leading to nowhere and doors which could only be opened from one side. The whole point was to allow Mudgett, also known as H.H. Holmes, to murder young women who visited from out of town, several of whom he married first. The story of H.H. Holmes is, without doubt, the only reason anyone ever picks up The Devil In The White City. That it is intertwined with a moderately-interesting account of the design and construction of the World’s Fair itself will be either a pleasant surprise or an annoying deviation, depending on taste.

Some short takes: When We Were Orphans is no one’s favourite Ishiguro novel (least of all his) and threw me into a bit of a funk when reading it, but a bad Ishiguro book is still a pretty good book. Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner? (answer: his unpaid mother) is a witty, feminist critique of homo economicus. I suspect the author would appreciate the themes of maternal self-sacrifice in Please Look After Mom, partly notable for being written in the second person. I chose The Tell-Tale Brain as a follow-up to Phantoms of the Brain, which I read years ago, and if you decide to join me you will spend days trying to shoehorn interesting neurological studies into unrelated conversations. I’ve read numerous variations of the Asian rags-to-riches-to-rags story which is told in How To Get Filthy Rich In Rising Asia, but this is a good and moving one. A Fine Balance, set during India’s ‘Emergency’ period of the mid-1970s, is a more demanding read but also a beautiful, sad story with wonderful and memorable characters. I grew very attached.

Finally, while it’s a terrible cliché to enjoy Nietzsche, it is very hard not to. He’s sharp and insightful, weaving a great historical narrative out of clever linguistic details (e.g. what is ‘good/evil’, and how does it differ from ‘good/bad’?) and, when he gets worked up, he can hold one hell of a shouting match with himself. One thing Nietzsche can’t do, however, is hold a candle to George Orwell. And so I want to conclude this lengthy review with praise for him, who can be enjoyed in Penguin’s collection of essays. Orwell possessed such a wise, prophetic and independent voice that he is admired and respected – without misrepresentation – by both the left and the right. But you should know, if you’ve only read his famous novels, that Orwell does a marvellous line in cultural history. He cares about comic books, murder mysteries and cooking – and he cares about how, and why, they change over time. He understands patriotism, understands how people think and behave (just read, for example, his description of which books are borrowed from libraries versus which books are bought from bookshops) and he does it in the finest, clearest prose. For Orwell, good writing is a political act, and he makes me feel illiterate. I wish he were still around to consult.

Confession: this year, I failed in my reading target of reading ‘at least one more book than last year’, which would have required a minimum of 31. I could make several attempts to excuse myself, not least an abandoned effort to read the King James Bible which consumed many hours, and the distractions of moving. Nonetheless, here is my year in books:

It started out well, with The End of the Chinese Dream. I’d been looking for a good book on China for a while and picked this intimate study of the hopes, dreams and fears of Chongqing residents over a general sprawling history. It’s particularly memorable for its account of using a traditional Chinese ‘wishing tree’ to subvert government restrictions on surveys. There’s a much broader narrative to Adam Tooze’s The Deluge, a history of the global political reshaping which followed the First World War, which I wanted to read something about in this centenary year. (Fun fact: once upon a time, I went to Tooze’s ‘Economics for Historians’ lectures.) Suffice to say, I really enjoyed this, and recommend it to anyone interested in how and why the twentieth century turned out as it did.

More surprisingly, another piece of non-fiction this year which really stuck with me was Addiction By Design – Natasha Dow Schüll’s study of machine gambling in Vegas. I think I read this after an extract in The Guardian happened to catch my eye, and I found it completely enthralling. Not being a gambler myself, I had always assumed that the pleasure of a place like Vegas would come from the thrill of taking risks. In fact, the majority of casino revenue is now made up of gaming formats which are geared to precisely the opposite: routinised, almost trance-like experiences at slot machines. A work supported by years of research, the author deserves credit for making it so accessible to a general audience.

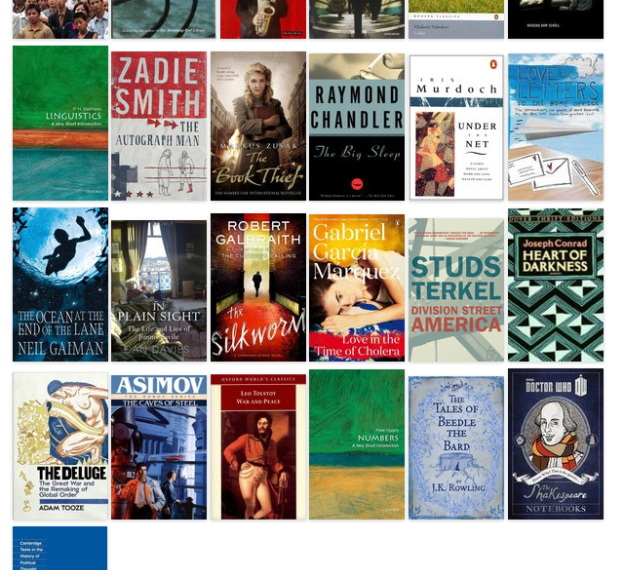

I’ve focused on non-fiction so far, which is where a lot of my hits of 2014 turns out to be, but there was a lot of good fiction stuff too. The Line of Beauty drew me into its world and served up some of the most well-written sex scenes I’ve ever read (your mileage may vary, but I remember being pretty struck by them). Heart of Darkness is a justified classic, obviously, and well conveys the dark and the terrible of European colonisation. The Caves of Steel was the first Asimov book I’ve ever read and, apart from being clever, imbued me with a strong, false nostalgia for the science fiction of the 1950s, and the kind of futures they imagined. The Ocean at the End of the Lane was vintage Gaiman: I’m not convinced it had much that was new, but I’m always a sucker for the twisted fairytale world he creates. And much of the pleasure of The Silkworm was the comfortable feeling of being allowed back into a JK Rowling book series, with characters you already know and love, ready for another adventure.

On the other hand, The Autograph Man was (as everybody warned me) Zadie Smith’s least best, and meanders around the lives of some fairly unlikeable but also unremarkable characters. I wasn’t particularly taken in by The Big Sleep: it was fine, and scratched an itch for a hard-boiled American detective, but I’m not in a rush for more of Philip Marlowe. Under The Net has somewhat slipped out of my brain, although I think I understood something from it at the time. The Book Thief was simplistic but moving. Love in the Time of Cholera is all about the writing, and that always stays with me less than plot, meaning that now when I look back I draw a blank although I remember enjoying it at the time. One thing which did stay with me was Lolita, so I’m glad that I tried again with this book after abandoning it halfway through a few years back. The first half is still much better, but it’s worth reading alone for Humbert’s skilful self-justification, all the creepier for its certain seductive power.

Oh yes, and late this year I also read War and Peace. I’m pleased that I did. Big epics usually take some time to get into, especially with so many characters, and this was no exception. But since the first thing most people say about War and Peace is how long it is, I have to say that it didn’t feel so long, especially once I could devote proper stretches of time to it. So, why bother? Well firstly, I knew next to nothing about Napoleon and the Napoleonic wars, so Tolstoy proved very instructive. The characters are pretty memorable, especially Natasha – after whom my sister was named! – and there are a couple of moments (especially during the war sequences toward the end) which hit you hard. He also throws in a couple of great quips.

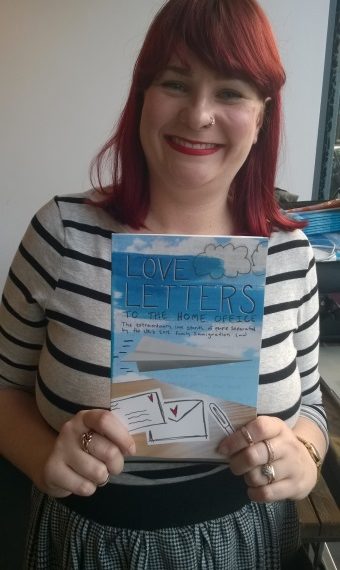

Many congratulations to Simon for appearing in the essay collection Going Underground. And many thanks to Christa, whose gift of Division Street America was not always easy to read, and often melancholy, but an important insight into the city of Chicago. Love Letters to the Home Office and The Life and Lies of Jimmy Savile I have written about elsewhere.

And finally, for anyone who’s still reading: sometimes, for whatever reason, something you read enters the ‘random useless fact’ part of your brain and stays there. So allow me to share two entirely unrelated things which I found interesting in my reading this year. Firstly, courtesy of Linguistics: A Very Short Introduction is the Tuyuca language of a small South American people. It’s one with mandatory evidentiality, which means that the grammar of the language requires you to specify how a statement is known – whether visually, nonvisually, secondhand or through being apparent or assumed. (Comparably, for example, English often forces you to specify whether a noun or singular or plural: you can’t ‘pick flowers’ where the number of flowers may be 1.) But just think how much more precise the news would be if we spoke Tuyuca, eh?

Second fact, this time from Rousseau: the Polish-Lithuanian parliament of the 16th-18th centuries had a procedure known as the liberum veto. If any member invoked it (by shouting “Nie pozwalam!”, Wikipedia claims), then it didn’t just crush the legislation being debated, it also brought the session to an immediate end and voided everything which had already been passed in that session already. For anyone who despairs at the banality of Republican obstructionism in the US Congress, take some comfort in the fact that at least they don’t have the liberum veto. (Rousseau wasn’t very impressed, either. He called for the death penalty for anyone who tried to use it.)

Abbi with the book

Tonight I was invited by Abbi to join the book launch of Love Letters to the Home Office, a collection of stories about families kept apart by the UK’s 2012 immigration laws. These reforms mandate a minimum income of almost £19,000 before you can begin to get your partner or your family home.

As it happens, I do know a little of what it’s like to say goodbye to someone you love at an airport, knowing that you have no legal right to stay in the same place together.

But that is nothing compared to the stories in this book:

“There’s a wee boy in Chandler, Arizona, USA. He’s 15 months old and his name is Robert. He has some baby toys but his favourite thing in the entire world isn’t a toy. Robert loves his mum’s Samsung tablet. He calls it ‘Da da’ and carries it around the house all the time.

Robert hasn’t seen his father since he was 6 months old. The tablet is all he knows of him. They talk on Skype when they can, but there isn’t always a good connection; he doesn’t understand why his dad is sometimes sad when they talk and play.”

This is an entirely fixable problem: we don’t have to keep families apart, it’s something this country’s leaders are choosing to do out of cowardice. For that matter, we don’t have to have an insanely bureaucratic, officious and expensive Home Office either. And this is something which should alarm all British citizens because – take it from me – you never know when you might find yourself in love with the ‘wrong’ nationality. Instead of looking for a system to pretend to protect us from the world outside, we should be demanding a system which gives us our rights as full, global citizens who can now trade, communicate, move from country to country and start families across borders more than ever before.

Go sign the petitions!

Success! For another year running, I’ve managed to meet my target of reading at least one more than last year’s total. And here they were:

Having discovered Ishiguro last year, in 2013 I greedily went back for more with A Pure View of Hills and Never Let Me Go. The latter was probably my favourite, although the theme of lying – mostly to ourselves – is always present in his works, and always compelling. Never Let Me Go is more subtle than a great social conspiracy: the characters are ‘told and not told’ about their world, which is very resonant. Truth, lies and storytelling is also central to Pullman’s short The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ but the story hasn’t stuck with me nearly as much. Perhaps it comes down to what you read as a child, but the image of the afterlife in His Dark Materials has always stayed with me as a frightening depiction of what religion would really entail. Nothing here came close in lasting imagery.

Someone else who got two books into my list this year was J.K. Rowling. I love J.K. Rowling, and I love how much gluttonous pleasure I get from her books in the same way (and this is my only Harry Potter comparison) that reading Harry Potter was addictive, and preferable to eating, sleeping or talking to real people. I mean, The Casual Vacancy was a joy, and an especially indulgent joy because it felt like a friend’s very funny skewering of a shared target: little England. There are plenty of other, more uncomfortable books to critique the flaws and hypocrisies of the city-dwelling, metropolitan middle class. (Cough.) But this was aimed at the snobbish claustrophobia of the suburbs instead, and felt like a better take down of the Daily Mail than any direct attack. That they obliged in calling it a “relentless socialist manifesto masquerading as literature crammed down your throat” by a “blinkered, Left-leaning demagogue” in return is the icing on the cake. I have less to say about The Cuckoo’s Calling, other than I also enjoyed it immensely and look forward to further adventures of Cormoran Strike.

And Then There Were None wins the award for most atmospheric read of the year: alone on a darkened evening in a quiet Welsh B&B, before getting to the end and wondering if anyone was going to jump out and kill me on my way to dinner. The Bloody Chamber was wonderful. (Does everyone else love Angela Carter yet? Good.) The Picture of Dorian Grey was flawed but interesting and confusing: what is Wilde trying to say about his own philosophy? The Blind Assassin was good but over-long, and that’s about all the emotion it summons up in me. I approached Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere with some hesitation, as it seemed that a fantasy novel set in a shadowy London underworld stuffed with Underground references was too good to be true, and bound to be a disappointment. Instead, I loved it, and it left me wanting more adventures in that world. And then right at the end of the year I ‘discovered’ Doris Lessing (to the extent that you can discover a Nobel prize-winning author first published in 1950) with the sad, haunting, sometimes scary The Grass Is Singing. Will definitely return to her in the next few years.

This year, the balance of injecting new authors alongside those I’d already read came largely from Book Club at work, and I’m really glad for it. Some of them I didn’t instinctively love (The Interrogative Mood, Are You My Mother?) but the discussion was always enjoyable and often made me retrospectively enjoy reading it, if that makes any sense at all. (Oh, the lies we tell ourselves…) Winesburg, Ohio just makes you want to shake the whole town and tell them to stop being so introspectivey European on us. And I think it’s almost a cliché for book clubs to read and then disagree massively on We Need To Talk About Kevin. Some hated it, some loved it… and I was kinda in the middle. I wanted to turn the (virtual) pages to find out what happened next, but the central characters seemed so absurdly distant from my actual experiences that it didn’t really matter much.

A more grounded view of growing up came from Melissa in What Should We Tell Our Daughters? – one of only a few non-fiction books this year. My abiding memory is reading this on the train, with Michele reading it over my shoulder and expressing frequent agreement, and just occasionally feeling a slightly hopeless feeling of ‘oh, the injustices are so layered and tug in so many different directions’. Lords of Finance was enjoyable although what stuck with me most was less about central banking and more about the sheer stupidity of the Treaty of Versailles, which is well trodden ground but well remembered as we go into 2014. And William Dalrymple’s From the Holy Mountain was somewhat infuriating, because despite being well-written and informative about a part of the world I’ve never seen, it assumes too much complicity from the reader in accepting that the decline of Christianity in the Middle East is something to be mourned beyond the immediate human suffering endured by its adherents.

I’ve already been on a book buying splurge for next year 😀