On Election Day morning, I head out on another canvassing ‘packet’ of doors to knock. The list is designed to identify known Democratic supporters with patchy voting records. Our aim is to remind them of their polling station, cajole them to come out early, ensure they don’t forget. One family is so sick of being pestered that they’ve stuck a cardboard sign to their front door with a smiley face, a voting sticker and the words “I voted today at 8.30am” in felt tip. They are a canvassing dream. But most people are not home, or pretending not to be. I scribble their polling location onto our campaign sticky note and add it to another door.

“What are you doing?” asks a man from his porch. “Hi, I’m Dominic and I’m volunteering with the Hillary Clinton campaign” I repeat for the hundredth time, walking over and straining to achieve ‘friendly’ and ‘approachable’.

“Are you coming to my house?”

Actually no, I explain. His house isn’t on the list. But is he voting for Clinton? He is. I try to shake his hand, and he turns it into a complicated fist bump which I fail to pass but he forgives. He’s maybe 40, and I understand maybe half of what he’s saying. This is not a normal problem for me, and hasn’t come up in any of the canvassing so far. I’m really not sure where he’s from, or what he’s telling me, but after a couple of attempts I realise he’s asking me about my jeans.

I’m feeling sensitive about my jeans, because the previous morning I was threatened off a nearby street by a group of men (plus dog) who objected to my “gay jeans” in the strongest possible terms. But this guy is merely making conversation and I try to think of a response. I look down, look back up, and then – in full and total awareness of the ridiculousness of what I’m about to say – break the silence with “thanks, they’re from Uniqlo!”.

Suffice to say, there is not a Starbucks in downtown Toledo, let alone Japanese casual wear. Many homes are boarded up or demolished. One woman told us about the parks, pools and ice skating rinks which used to exist when she was growing up, but they are all gone now, along with the manufacturing which paid for them. The city is deserted, especially at weekends. Its remaining residents could be Trump’s imagined target audience, except they aren’t white. (On average, Trump voters are actually richer, and live further out.)

Even to annoying canvassers, however, people here are kind and generous with their time. One undecided voter appears at his door with his hand over his mouth and apologises for yawning: he was recording a studio session late last night. From his t-shirt and voting priorities, I guess Christian music. He thanks me with ultra-American Midwestern politeness for trying to sway him to Clinton. Another woman gives me a hug because she likes my accent. (She’s into languages and speaks some French, Spanish and Swahili.) In one strange encounter, a man agrees to vote early today because thinks he can make it before 5pm. I’m pleased, but I wasn’t expecting him to literally close his apartment door and walk off to vote the next moment without even stopping to pick up a coat. (Later on, when I see the multi-hour queue at the early voting centre, I feel guilty.)

And then there are the real heroes. Starting, of course, with the campaign team and volunteers who welcome and feed us like family despite us only showing up for the final four days. The young, homeless woman who sees my t-shirt and approaches me with enthusiasm to ask if she can still vote for Hillary. (She’s registered in Detroit, so she can’t.) There’s Monica, standing outside a polling station in support of renewing the city’s zoo levy, who buys us hot chocolate as we hand out Democratic sample ballots. Later, a local Republican and his 14 year old son show up to give out the Republican equivalent. He is kind to us, and we chat amiably, and for a brief moment there is a tiny window into civil democracy which is probably more widespread, even now, than you might think.

My favourite person is the young man who rescues us from the seventh floor of an apartment building, after Randi and I tailgate and then realise you need a keycard to get out as well as in. Pushing my luck, I ask if he’d lend us his keycard for an hour so we can canvass the whole building, and he agrees on account of it being for Hillary.

I thought it might be better to write about these people, who made life better for me, Randi and Christina in Toledo, rather than writing the same thing about Trump you can find on your Facebook feed. It is not supposed to be an uplifting distraction. These are good people who will be hurt by President Trump. They will be hurt in the worst-case scenarios, and they will be hurt in the ‘best-case’ scenarios where Trump is ‘only’ a Republican and ‘only’ does generic Republican things. I am sorry.

I have a jokey conspiracy theory that Scientology is just a front organisation, cobbled together by other world religions to improve their reputations. It’s easy to declare that the idea of Lord Xenu isn’t inherently more ridiculous than an eternal dinner party in heaven, but the Church of Scientology gives people the heebie-jeebies in a way that the Archbishop of Canterbury never will. And after spending Tuesday evening with the Hubbardites, it’s easy to see why.

The adventure began after mistakenly receiving a Golden Age of Tech II DVD in the mail. We enjoyed it so much that we went binge-watching Scientology documentaries, concluding with HBO’s new Going Clear film a few weeks ago. (Sad fact: plans to broadcast it in the UK are running into trouble because the recent libel law reforms don’t cover Northern Ireland. This needs to get fixed.) So how better to round off the experience than a visit to their centre in Chicago?

Taking the ‘personality test’

Now I admit: four prospective customers arriving together is a bit of a stretch, and I’m sure they smelled a rat. And as soon as we mentioned the Golden Age of Tech II they were immediately agitated, stressing repeatedly that we “shouldn’t have got that” and “it won’t have made any sense”. As many others have noted, Scientology is the only ‘religion’ which jealously guards its belief system from outsiders.

Nonetheless, they were welcoming enough, and quickly offered us the famous ‘free personality tests’ which we gratefully accepted. This is termed the Oxford Capacity Analysis, presumably to suggest a (bogus) connection with the university – a neat touch, unless you went to Cambridge, in which case it’s simply off-putting. The test is also dated to 1978, and it shows. “Do you believe the modern ‘prison without bars’ system is doomed to failure?” it asks, confusing 21st century Americans who notice rather a lot of bars around their prisons. I also had to decode the meaning of the ‘color [sic] bar’ (thanks, History GCSE!).

Even harder to answer are questions about how other people perceive you: is your voice monotonous? Do people think you talk too much? Do they criticise you to others? As far as I’m concerned, my friends and acquaintances have (presumably) always had the good manners to swap notes on how terrible I am behind my back, and as a sensitive soul I’d prefer it to stay this way. But like someone who corners you in a dark alley and asks for the time, the searing obviousness of the ploy feels insulting. At least go to the effort to hand-make some insecurities for me, rather than a cookie-cutter multiple choice quiz.

Anyway, after the test we were led into a small, darkened room to watch an introductory video about the history of Dianetics. (In another blunder, it transpired afterwards that they actually showed us the ‘wrong one’ – I hope someone senior in the Church is reading this.) With acting worse than a Star Wars prequel, we were led through the early struggles of Scientologists to gift Dianetics to the people in the 1950s. To give due deference to L Ron Hubbard, who might as well wander about with ‘cult of personality’ written on a sandwich board, you only see the back of his head. You do see, in a particularly choice moment, a gathering of the American Psychiatry Association – Scientology’s chief villains – wearing torn lab coats and performing lobotomies in some gloomy basement somewhere. But thankfully, Dianetics becomes a worldwide sensation anyway, and soon everyone is putting it into practice in all walks of life.

Hang on. Dianetics, just to be clear, is a watertight theory with a 100% success rate of mind-over-matter medical healing. The central character in the film avoids getting his infected leg amputated after a few bedside chats with Hubbard, for goodness sake. And then in the following decades it sweeps the world. But isn’t this the same world I’ve been living in for the past 25 years? Why have I been wasting money on dentists if this has already taken over?

My results

Lay these thoughts aside for a moment, because it’s time for the test results! For this we were separated for one-on-one discussions – not a particularly relaxing prospect. This tension heightened when Catherine was accused of swapping answers with me, and I was challenged for saying that my biggest Life Problem (capitalisation © Church of Scientology) was the quality of American cheese in supermarkets.

“Is this really your biggest life problem?”

“Have you ever tried American cheese? It’s a problem.”

“I’ve tried lots of cheese. But this speaks to your test results: you don’t admit your true feelings to others.”

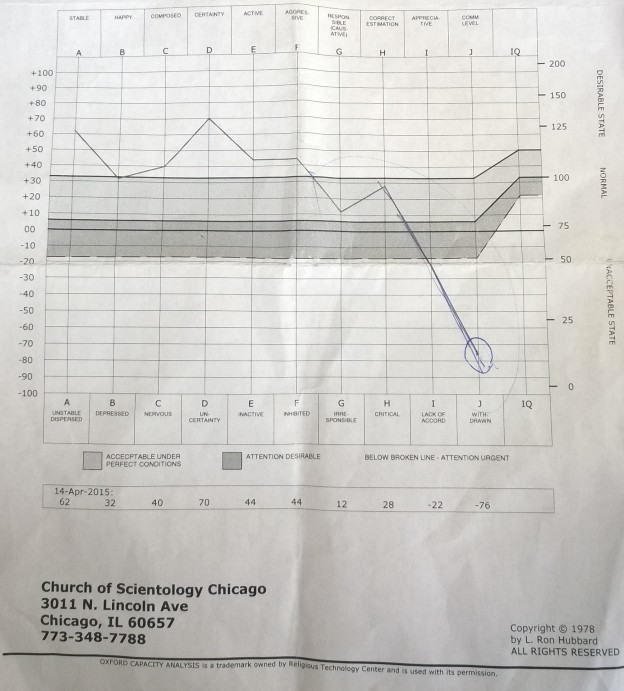

Yes, as you can see above, I score relatively well for ‘stable’ and ‘happy’ and ‘aggressive’ (come to your own conclusions about why ‘aggressive’ is at the positive end of the scale) but am let down massively by my withdrawn nature. I am, to speak precisely, -76 out of -100, which sounds perilously close to lock-me-in-a-room-and-shut-the-door territory. “Attention urgent” , the test says, although really this felt more like a nationality test than anything else. Admitting your true feelings to others is a slippery slope to Americanisation, and in any case, it doesn’t really equate to ‘shy’.

“Do you feel shy?”

“Not really…”

Silence followed, and to move things along I felt compelled to cold-read myself. “I guess, when there’s a bunch of people I don’t know already, I feel less confident than among my friends…” She nodded, approvingly. And then tried to sell me a book.

If this doesn’t feel like a church to you, that’s exactly the point. There is something mindblowing about the historical twists and turns of religions: that the outcome of arguments at the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE (!) helped decide what millions of Americans pray about every Sunday is as good an argument as any for why history is pretty fucking cool. In contrast, the intellectual lineage of Scientology is dreary 1950s psuedoscience and the “what type of thinker are you?” language you expect at a management consultancy ice-breaker. To what extent is Scientology’s limited success simply the remnants of a post-war moment: a new wave of college kids being exposed to faddish philosophies for the first time, and an enthusiasm for science and technology without enough popular understanding of what ‘science’ really means?

As we left, we all received free copies of Hubbard’s The Way to Happiness booklet. And so to end on a note of unity with Scientology, I wanted to quote the conclusion of chapter 8 (murder):

The way to happiness does not include murdering or your friends, your family or yourself being murdered.

Well at least we can all agree on that, right guys?

Jesus paid it all,

All to Him I owe;

Sin had left a crimson stain,

He washed it white as snow.(Spotify)

We huddle along our row as the band plays. The balcony affords an excellent view of the auditorium: not full, but certainly not sparsely populated either. This is Willow Creek Community Church in Barrington, Illinois. It’s less than an hour’s drive from Chicago and averages 24,000 attendees over a weekend, according to Wikipedia, making it America’s third largest church. And Ellen has kindly driven me, Randi and Kannan to have a look.

I’ve a feeling we’re not in the C of E anymore

After the half hour concert is over, the ‘Director of Section Communities’ runs through some administrative items and monetary collections. Those watching online are encouraged to donate through the website, and everyone is shown a glossy video of the international projects the church is involved in. But soon we move on to Steve Carter, teaching pastor, whose talk this week will be on ‘the reality of heaven’. (The whole thing is archived on their website.)

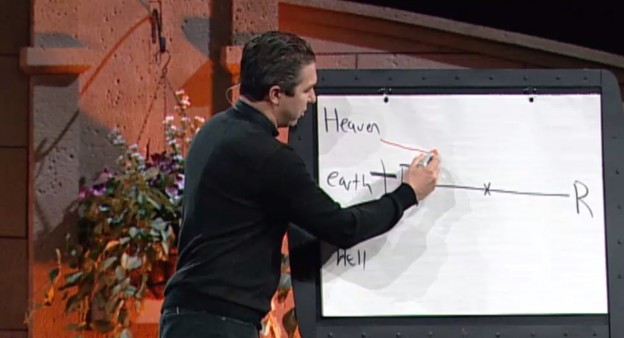

I quite like Steve. I’m frequently frustrated when religious leaders fail to discuss the actual implications of ideas like ‘the afterlife’ outside of ritual or absurdly generalised metaphor. Steve certainly can’t be accused of that – he even draws a diagram, so you know exactly where everything sits.

Heaven, Earth, Hell

Of course, the downside of not using absurdly generalised metaphor is being absurdly specific and literal. Taking our cues from CS Lewis, we envisage heaven through the Bible’s imagery of dinner parties, weddings, cities and concerts. “It doesn’t seem boring to me”, Steve declares, but it doesn’t take a great leap of imagination to wonder how many performances of Jesus Paid It All you’d be able to take. Alas, when it comes to hell he reverts to the now ubiquitous “separation from God” soundbite, quickly drawing a veil over eternal damnation. He also tells a story about discovering that his long-lost biological father had died, but not before coming to the faith, and thereby raising the prospect of joyful reunion in heaven. Which is all very well, but who asks the obvious question: what if he hadn’t?

After the sermon, Randi and I queue up to ask questions. She wants to know if Jews get into heaven (it’s unclear), and as ever I’m curious if his God would grant my dying wish to opt-out of any afterlife altogether. Steve doesn’t pretend to have concrete answers, but can’t understand why anyone would want that. “In my experience, people who say that are really motivated by a fear, deep down, that they wouldn’t get in.” And here we stand smiling at each other, stranded on opposite banks of comprehension. Can it really be true that he doesn’t understand the torture of immortality? I almost want to start going to their Alpha courses to try and bring him round. But I think church conversions are only supposed to happen in one direction.

On the drive back, Randi is unimpressed with the lax demands placed on the congregation. The most we ever heard from the Bible at this big, non-denomination gathering was short quotes appearing as captions on giant screens – a long way from multi-hour Torah readings. In a competitive marketplace of religion, the distinction between worshipper and customer is not always clear. Even the song lyrics are full of monetary metaphor: Jesus paid, we are ransomed.

I’m sure those who run Willow Creek would say that church ought to be a joyful, celebratory experience. It certainly seemed so for its parishioners – a more diverse crowd than you often see acting together in Chicago, it’s fair to say. There’s even a sign language translation for the deaf. But in the end, I’m not much moved whether a church is dour or rich. It’s the ideas which are more interesting, and no matter how catchy the song, sin’s ‘crimson stain’ still invites a question: are we really born broken? Do we need to be ‘saved’? And who wants to live forever?

In Part 2, we’ll visit the Church of Scientology for some ‘free personality tests’.

We put down our $10.25 plastic cups of Budweiser to stand for the national anthem. As the arena goes dark, the screens fill with the American flag and stock footage of a bald eagle. Speaking strictly musically, it is a very odd song. By the time we get to “land of the free” cheering has already broken out – partly from pure relief, it feels like, of the singer’s successful scaling of the octaves.

When Katie first announced at work that she was going to a Monster Truck rally at the weekend, I laughed at her. By late evening, I was sending begging texts asking to come along. I can go to all the nice parties and restaurants here that I want, but there are nice parties and restaurants everywhere. Watching comically oversized trucks compete to spin around in circles and leap over dummy cars: this seemed like a reasonably American opportunity. (“…the 2014 Monster Jam tour schedule will unfortunately not include an event in the UK”, their website informs fans. They are, however, “working diligently to have Monster Jam return in 2015”.)

If you’re imagining something rugged and cowboy, you’re in for a disappointment. The keynote of Monster Jam is family-friendly, and most people are here with young children. Think sports entertainment, in much the same vein as wrestling. The atmosphere, diesel fumes and sticky floors aside, is really pretty sweet. Suitably cute children are picked from the crowd and rewarded with free tickets to next year’s event. (It’s OK, the promoters will make it back on the hot dogs.)

Those things which are culturally dominant are often invisible. So it is with monster trucks. The thrill of watching a failed jump – seeing the truck yield backwards to gravity and land upside-down with a thump, smashing its windows in the process – this is probably universal. We’re all secretly wondering if a bloodied driver is about to be pulled out from underneath… whether the lights will dim unexpectedly for an unexpected tragedy. Of course, it didn’t. Of course, everything was fine. But as we warm to the fake-danger on stage, half the audience has already slipped in their ear buds. We’ve become accustomed to a culture which sees nothing strange in this – like selling anoraks in the queue for a water ride. Spectacle shouldn’t just be risk-free – it ought to be discomfort-free, too. A reasonable aspiration, perhaps, but it pushes ever wider the gap between our controlled experiences and the messy complications of ‘real life’.

We walk back to the train station to get some exercise. It’s about 5 kilometres – waiting for the bus (or, of course, jumping in the car) would be as normal in Britain as in America. Less common are the half-hearted attempts at sidewalks, which – to be fair – are often buried in snow. Running across the intersections feels greatly more dangerous than anything back at Monster Jam, but it’s also quite exhilarating.

Near the station, we pass the Rosemont Public Safety building. Their insignia is a hammer crossed with a machine gun. There’s no sign of any ear buds, but I wouldn’t be surprised.

Once upon a time, a very long time ago on the planet Earth, a species of ape evolved named homo sapiens sapiens, or human beings. At first glance, there seemed to be a lot wrong with these creatures. Their hips were too narrow, their two feet exposed their upright bellies to the world, and when they got frightened little goosebumps on their skin tried in vain to puff out non-existent hair in a futile attempt to look bigger and stronger than they really were.

But human beings had some tricks up their yet-to-be-invented sleeves, too. Their opposable thumbs helped them to fashion tools to make up for their deficiencies. With their special brains, they joined sounds to the world around them. And they were born to be social: they shared these sounds with other human beings, passing them on one to another, making connections, looking for patterns. Not all of the sounds were for the here and now. One human could tell another what was ‘over there’, or ‘back then’, or even ‘yet to be’. They could even imagine things which had never existed at all. Not bad for a hairless ape.

These animals were different to us, but also the same. They had not yet imagined credit cards, original sin or international shipping. But they did know, at least among those who made it to the northern fringes of their planet, that it gets dark at this time of year. The days turn to nights almost as soon as they have begun, and the air is cold, and the trees are bare. It is not an easy time if your body must keep its blood warmer than its surroundings, never letting up for a single moment, just to stay alive.

Some animals sleep through the winter, but apes must see it out. And so they turned to their sounds, their words, and their stories. They told each other, at the darkest moments, that the light would come back. They began to celebrate, and drink, and feast together. They gave each other gifts, and made fires from the logs of trees, and sang songs of the harvests to come.

There are lots of songs, lots of stories and now lots and lots of humans. But Christmas, which is older and wiser than the name it now wears, is not about any particular one of them. It is about the coming together – those apes in the dark – and what they choose to share with each other. And if you celebrate it, you might take a moment to remember our collective ancestors, and how we owe our existence to their making it through.

Oh, and it’s also about hats: