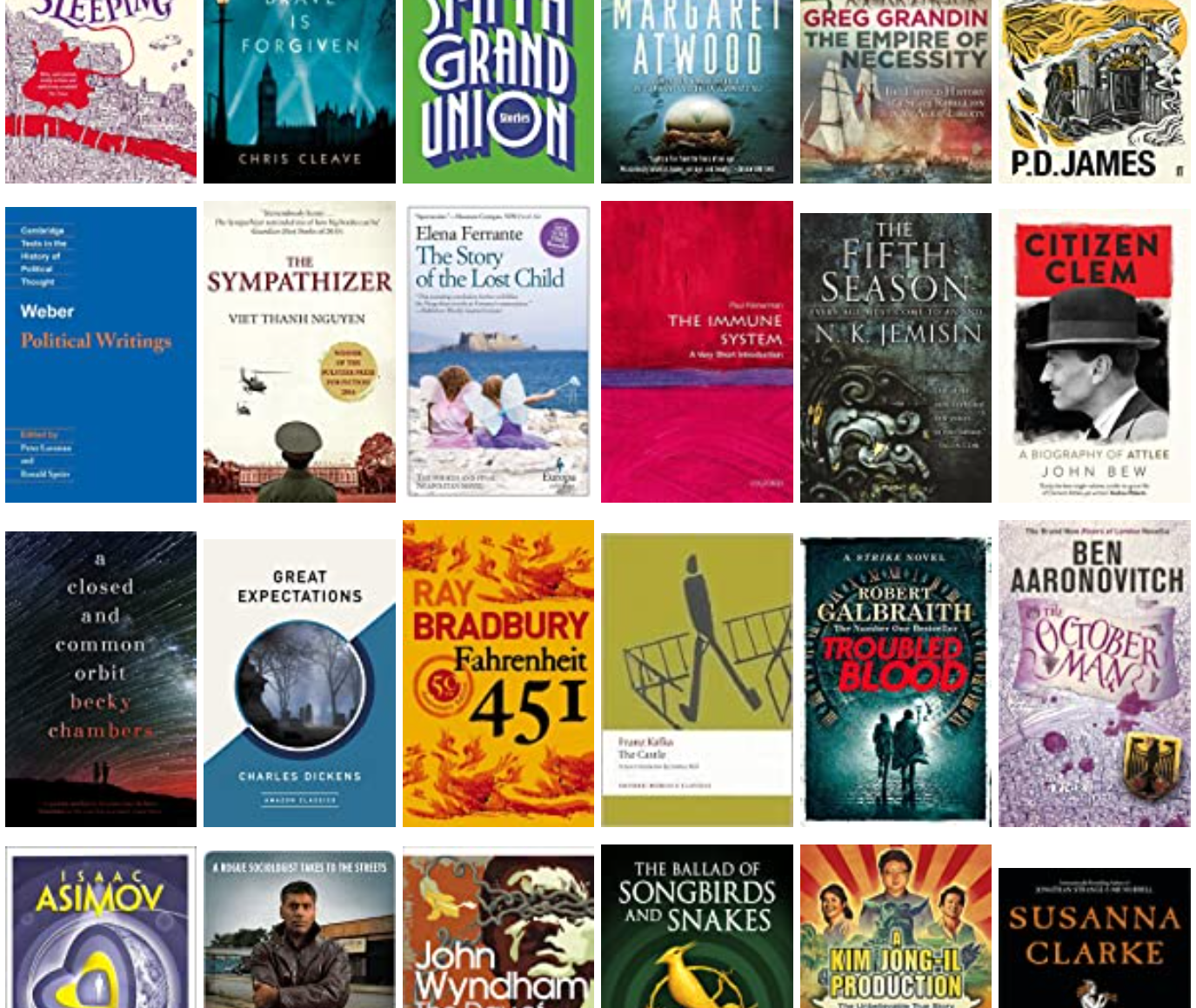

When lockdown began I did think that one silver lining might be having more time to myself to read. It didn’t really work out that way – sitting in the same room all day just isn’t that stimulating, I guess – so I’m closing out the year with a total of 35 books read which is a little down on last year. Still, I covered a lot of good books which I’m excited to share here, albeit with a heavy dose of comfort from reading ongoing series which I was already invested in. Mild spoilers below!

Fiction

I spent the whole of January reading The Wise Man’s Fear, the second installment in Patrick Rothfuss as-yet-unfinished Kingkiller Chronicles trilogy. The first book was my favourite read of 2019 and while the sequel was still very enjoyable it definitely suffers from ‘middle book syndrome’ of neither establishing the characters nor providing a resolution. Large chunks of the book feel like a frustrating side-quest which deviates away from the central story (the scenes with the Fae in the forest being the worst) but, of course, I will still be jumping on the third book with delight whenever it finally comes out.

Continuing with series, this year I reached the chronological end of Asimov’s epic Foundation saga with Foundation’s Edge and Foundation and Earth. The former was better, building to a wonderful climax where the Laws of Robotics suddenly re-emerge after a long, long gap: a cool and rewarding feeling of joined-up-ness with the first Asimov novels I started all the way back in 2014. The problem with the latter book is that – although Asimov has never been a character writer – Trevize is actively obnoxious enough to be distracting. There’s an amazing tease at the end, however, with the reappearance of Daneel, a decision to unite the galaxy against potentially hostile external forces and a hint that perhaps they are already among us. It’s a little sad that this is as far as Asimov went, although I’m looking forward to rounding off the series with his two Foundation prequels.

I also concluded Margaret Atwood’s post-apocalyptic trilogy with MaddAddam, which started really well but then went a bit heavy on flashbacks. To some extent this makes sense – things don’t tend to progress much in post-apocalyptic worlds – but it prevents character arcs such as Jimmy and Amanda from progressing as much as I’d have liked. Still, this was a great trilogy overall which doesn’t punish readers for taking a break between books. For a sequel which I enjoyed even more than the original, though, there was Becky Chambers’s A Closed and Common Orbit: the second in her Wayfarers series. I just immediately fell into this book – the same enthralling and optimistic world as the first one, but with a much stronger plot drive. It’s easy to praise sci-fi for being ‘dark’ but it takes skill to create something lighter without being lightweight, and I’m grateful for it.

And then there was The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, a prequel to the young adult Hunger Games trilogy. It was a decent enough read but suffers from the same problem as the Star Wars prequels: you already know that young Cornelius Snow’s journey is going to end in tragedy and evil, since he’s Cornelius Snow, so a lot of the book is spent just sorta waiting for that to happen. Plus his character does seem to swing a little wildly (even allowing for being a teenager) and the ‘romance’ with his Games mentee, Lucy Gray, is very creepy indeed.

In case you think all of my series are sci-fi and fantasy I also finished Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels this year with Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay and The Story of the Lost Child. They all blur together in my head as it’s all one long story, but I do remember feeling satisfied by the callback of the lost dolls at the end. Annoyingly I failed to make any notes about The Sympathizer but I was impressed by this North Vietnamese spy story (shades of Angela Carter about the Hollywood filming scenes) and unimpressed by my predictable failure to guess the identity of the commissar to whom the narrator is writing. Talking of spies: Eric Ambler is the gift who keeps on giving, years after Simon recommended him, and Epitaph for a Spy is another reliable interwar thriller of an ordinary man thrown into the deep end of espionage. The perfect pick-me-up.

When the country first went into lockdown it felt like the right moment for some familiar ‘London during WW2’ background vibes which Everything Brave Is Forgiven delivered well. To capture contemporary London I used to turn to Zadie Smith but sadly she now lives in New York and – perhaps this is Chicago rubbing off on me – I found the more New York-y episodes of her new Grand Union short story collection sparked some generic irritation in me. My favourite was ‘Big Week’… perhaps because it’s set in Boston instead.

Never mind, there are always London-based classics like Dickens’s Great Expectations to raise the spirits. Although we analysed the opening scenes to death in GCSE English I had never read the full book (or any Dickens novel) until now, and I’m so glad I finally did. He’s far funnier and snappier than I’d expected – in fact, reading this made me realise how perfectly Armando Iannucci captured the tone and humour of Dickens in his David Copperfield adaption. It is, of course, Dickens’s characters which shine brightest and it may or may not say something terrible about me that my favourite was the lawyerly but impressive Jaggers. It was also fascinating to learn about the controversy over the novel’s ending. The fashionable opinion seems to be that Dickens’s original, more downbeat ending is superior but, to me, the poignant final scene between Pip and Estella (which I had totally misremembered and was expecting to be a straightforward happily-ever-after affair) stays on just the right side of hopeful. Perhaps this is a strange comparison, but it reminded me of David Brent’s final scenes in The Office. Anyway: in conclusion, Charles Dickens is great.

I’ve loved so many of Ray Bradbury’s short stories but Fahrenheit 451 disappointed me. Counterintuitively, it’s more about the long-term effects of mass media on a population than the deliberate censorship which the title suggests, but it just didn’t click for me and suffers in comparison to 1984. Kafka’s The Castle, another classic, could also be frustrating but ultimately felt more meaningful. Kafka is very good at conveying the futility of the main character’s endless chase for what is simultaneously unobtainable and unimportant, and his writing is so immediately recognisable… although nowadays I can’t help but be reminded of Ishiguro which is a little backwards! (Side note: you know it’s been a stressful day of work when you sit down on the sofa and think “ah, yes, some Kafka is what I need”.) Meanwhile, landing straight in the “this is so much better than I thought it would be – why didn’t I read this long ago?” bucket is the 1950s British sci-fi classic The Day of the Triffids. The triffids themselves are perfectly nasty creations: carnivorous plants which will give you nightmares.

Piranesi, Susanna Clarke’s new novel after a long wait, was fantastic. I read it avidly in a few sittings and as it percolated around my head afterwards my admiration only grew. It’s a hard book to describe but has echoes of the famous Peter Capaldi Doctor Who episode Heaven Sent – a haunting, dreamy puzzle of a book with a complex, paradoxical message about innocence and faith which I could imagine really struggling with but absolutely loved. Gilead, on the other hand, is a book about faith which I deeply admire but cannot quite connect to in the same way. Written as a series of letters from a sick, elderly Reverend to his young son, there’s nothing for me to criticise or critique – and I do sense the meditative beauty – but at the end of the day it’s something like Piranesi which really sticks with me.

I was also engrossed by the latest Cormoran Strike novel, Troubled Blood, staying up late on the sofa to keep reading it while trying not to get too creeped out. Sadly the ongoing controversy around JK Rowling casts a shadow over the communal enjoyment of a series like this, but within the fictional world of Strike and Robin it is always exciting to be amongst old friends and see their relationship moving along. Similarly, it was nice to be back with magician copper Peter Grant in Ben Aaronovitch’s Lies Sleeping. I’m now at book seven which felt like the end of an era, with resolutions (perhaps!) for both the Faceless Man and Lesley May. Still, there’s more to come, which is just as well since the brief outing of German policeman Tobias Winter in The October Man novella proves that Aaronovitch really can’t let go of Peter’s narrative voice even if he tries.

Finally, though, I’d really just like to sing the praises of NK Jemisin’s The Broken Earth trilogy, or at least the first two parts (The Fifth Season and The Obelisk Gate) which I read this year. Where to start? These books have been on my to-read list for a while but especially so after her worldbuilding podcast episode with Ezra Klein. And it’s true, the worldbuilding is incredible here: from the big-picture – a geothermically unstable supercontinent where a persecuted few have the power of ‘orogeny’ to manipulate seismic events – to the smallest details. There’s no ‘Mother Earth’ here: it’s Father Earth, or Evil Earth, although my favourite example of these worldbuilding touches has to be the customary drink ‘safe’ which reacts to foreign substances by changing colour. But Jemisin hasn’t just created an intriguing world – there’s also a rip-roaring plot, an epic, tragic, multi-millennial intrigue and characters who are complex, layered and believable. It’s not all easy reading; the violence is well-written enough to make me flinch. But I have really savoured these books so far and cannot wait for the finale.

Non-Fiction

If I only had one non-fiction recommendation this year it would be Mehrsa Baradaran’s The Color of Money, which traces the history of the racial wealth gap in the US through the prism of “Black banking” and “Black capitalism” initiatives. It might seem odd to focus on these small and often troubled banks given how miniscule they are as a share of the overall economy, but Baradaran’s whole point is that the policy obsession with these concepts (most recently as ‘Enterprise Zones’) is a wasteful detour because they simply can’t function as normal banks which multiply wealth by lending out money. Anyone familiar with the racial wealth gap – and holds it carefully apart from ‘income’, which is very different – will know that it always comes back to segregated housing, particularly Black homes which did not appreciate in value or benefit from federally-backed mortgages. I loved this book for many reasons, one of which is its careful academic grounding in politics and economy of the US, so readers should avoid copy-and-pasting its conclusions to the UK or elsewhere. But the relationship between housing, banking and credit is deeply significant in Britain too and worth reading about in detail.

My mandatory entry in the ‘Political Thought’ series this year was Max Weber’s Political Writings, which I looked forward to because Weber is a legend and everyone has their favourite Max Weber quotes. (OK, perhaps not everyone.) In the run-up to his most famous essay on ‘The Profession and Vocation of Politics’ – which is well-worth reading alone, particularly if you’re lucky enough to have David Runciman’s explanatory lecture appear in your podcast feed at exactly the right time – I pocketed my own nuggets: on purity politics (“the right… to enjoy the intoxicating thought that ‘the world is full of such dreadfully bad people'”), the inadequacy of referendums (“most conflicting reasons can give rise to a ‘no’ if there is no… process of negotiation”) and non-parliamentary systems (“the voter is deluded as to the true identity of the person guilty of maladministration”). I’m not saying I read Weber solely to confirm my own biases… but who can resist indulging a little along the way?

Sticking with a politics-heavy year, I also read John Bew’s long but worthwhile biography of Clement Attlee, Citizen Clem. Attlee is a bit of a weird figure in British politics because his legacy is totemic, and many different groups now claim his legacy as their own, but unlike Churchill or Thatcher it’s hard to get much of an impression of what Attlee as a person was really like. In his day he often cut an uninspiring, uncharismatic and compromised figure – indeed, you get the sense that Bew is constantly apologising for picking someone so ill-suited to a heroic biography. The constant sniping from Attlee’s contemporaries, whose political heirs now appropriate his image, would have made this book too painful to read before Starmer’s election as Labour leader. But now there are glimmerings of hope that the real tradition of Clement Attlee, as he actually was, may yet emerge in British politics once more.

Gang Leader for a Day is unusual for a book about Chicago’s housing projects in that it’s (mostly) not written to shock. Set in the Robert Taylor homes (since demolished, but the aerial photos remain breathtaking for how large and other-worldly they were) it has some fascinating insights into the economics, management styles and gender dynamics of the gangs which operated there. (I was particularly struck by the minimum wage rates for frontline dealers.) Meanwhile, in North Korea, A Kim Jong-Il Production is less insightful but is gifted with the incredibly strange true story of the kidnapping of a famous South Korean movie couple so that they could make films for Kim Jong-Il. I hadn’t realised just how many kidnappings were orchestrated from North Korea and will never forget learning about Kim’s personal global film piracy operation so that he (and he alone) could enjoy foreign cinema.

Finally, Katie gifted me Randall Monroe’s brilliant What If? for my birthday, or “serious scientific answers to absurd hypothetical questions”. It’s the kind of book which makes you want to interrupt other people’s reading with interesting facts (sorry!) but the two which really stuck with me are the all-female species of salamander who reproduce asexually but use a courtship ritual with male salamanders from related species as a simulated ‘trigger’ to breed and Randall’s musings on how throwing a ball is actually really hard. No, seriously, the length of time for nerve impulses to travel down your arm is much longer than the half-millisecond timing error which would cause a baseball pitcher to miss the strike zone…