The slow decline of my reading total continues, with only 29 books completed in 2021. That said, writing my annual recap has left me feeling pretty upbeat about the quality of books I got through this year. So if you’re looking for inspiration, I hope you find something which intrigues you in the selection below!

Fiction

The first book I read each year often sticks in my mind and Meg Wolitzer’s The Interestings is no exception. I chose it as a deliberate palette cleanser from sci-fi and fantasy, and despite a lack of alien invasions this character-driven novel about the intersecting fates of a group of teenagers who meet at a summer camp in the 1970s never felt slow. Sadly, it did strike me as a little unbelievable that the wealthy Wolfs would be so terrified of a rape trial for their son Goodman given how unlikely a conviction would be, and I would have liked to have learnt a little more about his accuser Cathy. But overall it’s noteworthy how fresh these characters and relationships have stayed with me over the year.

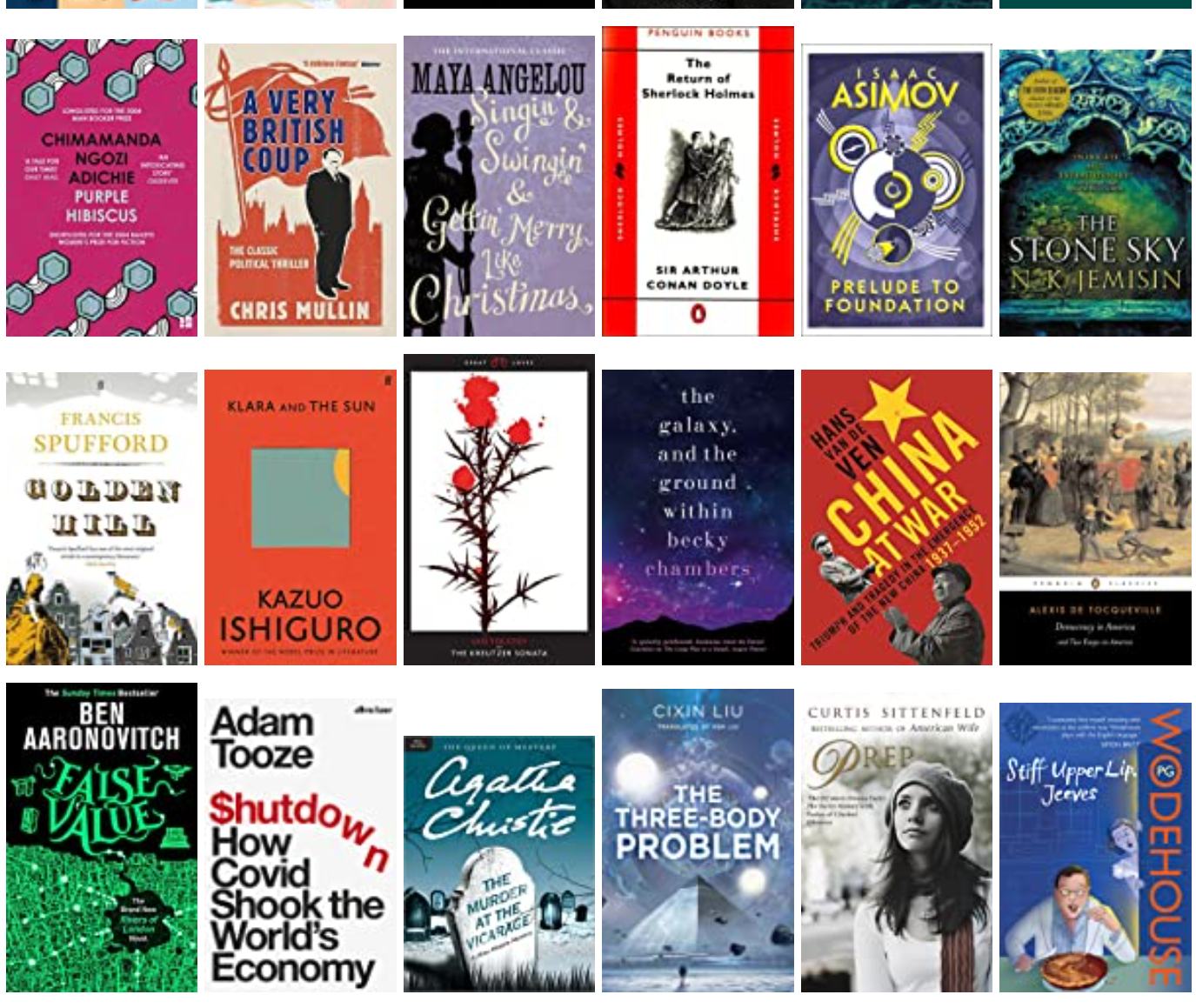

I put off reading Purple Hibiscus for a while because I was told it was intensely sad, but actually there’s plenty of hope in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s debut novel too. It’s a tighter, more contained book than Half of a Yellow Sun (still my favourite) about a fifteen year-old girl, Kambili, whose family is kept under tight control by her professionally heroic but domestically abusive father. Its beautifully written, and I enjoyed reading another novel in a Nigerian setting. Also, I have so much love for Aunty Ifeoma who takes care of Kambili and her brother for a portion of the book.

The obvious thing to do with Stuart Turton’s The Devil and the Dark Water is to compare it to The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle, his first book, and conclude that it’s nowhere near as gripping as that. But, judging on its own merits, this is still a fun blend of detective and/or supernatural horrors set in the evocative, claustrophobic world of a seventeenth-century ocean voyage. Klara and the Sun, meanwhile, is up there close to the best of Ishiguro even if, deep down, you start to wonder if all Ishiguro novels are shades of the same story. In this variant, the perceptive-but-not-fully-understanding protagonist is an ‘Artificial Friend’, Klara, who cares for a sick fourteen year-old child, Josie. It’s a haunting and beautiful story, with themes of loss, sacrifice and love, and if you’re already a fan of Ishiguro you’ve probably read this already anyway.

This year I completed N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy with The Stone Sky, and this remains one of the most outstanding series I’ve ever read. I’ve also nearly finished Asimov’s Foundation series with the first of his two prequels, Prelude to Foundation. You’re never going to read this for the complex plotting or characters – who always hop from place to place in search of something – but the story continues to bind the whole series closer to Asimov’s Robot books in a satisfying way. Talking of sci-fi series: in 2021 I also completed Becky Chambers’s Wayfarers novels with Record of a Spaceborn Few (featuring the human community of the Exodus Fleet trying to hold on to its traditions) and The Galaxy, and the Ground Within (strangers trapped by circumstance at an interstellar rest stop). The former was probably my favourite plot-wise for its clever interweaving of the characters’ stories, but I do hope the author changes her mind about the latter being the ‘final’ entry in the series and writes more at some point.

Sometimes you get lucky about when and where you read a book. I had Prep on my list for years as a recommendation from Melissa, but didn’t happen to pick up this emotionally intense coming-of-age story until I was sitting in Randi’s parents’ sunny back garden and had the time to fully immerse myself. Lee Fiora is a fourteen year-old Midwesterner who ends up at an elite, monied boarding school in Massachusetts. As you might expect, she struggles to find her place and excels at self-sabotage, so much so you want to shake her and tell her to stop messing everything up. But I really enjoyed reading it and found it a refreshing change from more high-concept books.

In Singin’ & Swingin’ and Gettin’ Merry Like Christmas, the third of Maya Angelou’s fictionalised autobiography, things are finally looking up for her! This volume especially connected to me with its background on the George Gershwin song Summertime, which I’ve always known but didn’t realise came from the 1935 opera Porgy and Bess or that Maya Angelou (who acquires the name in this book) performed in its 1950s European tour. On the topic of American history, reading Golden Hill (on loan from my mum) made me very curious as to whether early American colonies actually celebrated Guy Fawkes night to any great extent. It took me a while to get into its impressive but slightly showy writing style, but over time I enjoyed following the mysterious Mr. Smith and his troublesome stay in New York. I also got close to guessing the ending.

I didn’t want to read A Very British Coup until Corbyn was no longer Labour leader (too painful) which means we’ve now passed the second wave of interest in this 1980s political thriller, originally written as a Cold War-era warning on how the murky British Establishment would bring down a socialist Labour government committed to unilateral disarmament and NATO withdrawal. Basically, Harry Perkins is an all-round decent bloke who somehow becomes Prime Minister without much scheming (which seems unlikely) and then assumes he’ll have free reign to implement a bucketload of highly controversial policies, all at once, without deigning to engage in the messy business of actual politics where you do deals, form alliances, pick priorities and choose between difficult trade-offs.

Obviously, it’s impossible not to feel sorry for Harry when his government is brought down through unfair, underhand and conspiratorial means. But at the same time, gimme a break. Even Bevan realised he would have to make peace with GPs to create the NHS. There’s also an infuriating sequence early on when Harry picks a British-made power plant from a close-to-bankrupt company over a cheaper American alternative, explicitly on the notion that there was “nothing to choose between the two… on safety grounds” (his words!) and then gets unbelievably lucky when the American option turns out to be prone to meltdowns. Good for him. But what’s the ideological takeaway here? Protectionism works because British power stations couldn’t explode? What’s his American equivalent supposed to do then?

The Kreutzer Sonata was a recommendation from Kira to demonstrate Tolstoy’s misogyny. I’d say it delivers on this pretty heartily, which makes it all the more baffling that this plea for abstinence as the only alternative to violence, jealousy and murder was published by Penguin in their ‘Great Loves’ series. The Stranger is Albert Camus’s short, gripping 1942 novella in which the main character drifts inexorably towards the guillotine. Given that it’s 2021 I probably should have started with The Plague, but that can be next. Serpentine was a short-but-sweet entry in the His Dark Materials universe, and a nice glimpse of Lyra growing up, albeit laced with sadness given the state of her relationship with Pan by the time of The Secret Commonwealth. And I can’t say anything about Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves except that I fear the moment looming when I officially run out of cheerful Jeeves and Wooster pick-me-ups.

After a long break, this year I also returned to the original detective who begat all others with the short story collection The Return of Sherlock Holmes. Even though Doyle had already ‘killed off’ Holmes in The Final Problem and was bullied into bringing him back, I actually got into this more than the previous stories and it felt like Doyle had really hit his stride with his beloved characters. (See, Becky Chambers, there’s a moral here for you.) Also, Holmes’s complaint that Watson is always “looking at everything from the point of view of a story” and choosing to”dwell on senstational details”, thereby ruining the instructive potential of his examples, is hilariously meta. Pleasingly, Agatha Christie’s first story featuring Miss Marple, The Murder at the Vicarage, pays tribute to Sherlock Holmes with a couple of sly nods. I both loved and feared Miss Marple herself, and while I wouldn’t want to be her neighbour I will definitely check back on her nosy investigating skills.

Parable of the Sower is the first of two instalments in Octavia Butler’s famous dystopian series. It’s a fairly gritty, near-future version of dystopia: this is an undisguised America of 2024 in which society has completely broken down into violent enclaves rather than a post-apocalyptic allegory with strong fantasy themes. The hero is a tough, determined teenager – Lauren – with the rare ability of ‘hyper-empathy’ which causes her to feel the physical pain of others. To be honest, I found the ‘hyper-empathy’ element to be the least interesting strand in an otherwise engaging narrative as Lauren leads a small group of survivors from her destroyed community along the US highway system to found a new community and expand on her religion of Earthseed, and I’m excited for the next volume.

This was an exciting year for me in Ben Aaronovitch’s Rivers of London series, as I finally came up to date with the latest books by reaching False Value and, for bonus content, the novella about Peter’s cousin What Abigail Did That Summer. False Value is an important moment for the series, since the last book had wrapped up the long-running plot threads, and it was nice to be able to start afresh with some new characters and a high-tech corporate setting ripe for parody. As a gullible idiot, I genuinely started by thinking Peter might have left his job and taken up private security work rather than be posing as an undercover agent. But of course he hasn’t. Meanwhile, Abigail’s adventure with the foxes of Hampstead Heath was a delight – especially as I started reading it the day after Christmas at Kenwood, so the Heath was all fresh in my mind. More, please!

I normally end this section by gushing about a novel which is already widely recognised and highly acclaimed. This year is no exception, I’m afraid, but if Liu Cixin’s brilliant The Three-Body Problem is still sitting on your to-read list then you should absolutely give it a try. Somehow, this book combines physics and Chinese history into a clock-ticking thriller, producing a philosophically rich but simultaneously page-turning read. Perhaps you’re getting a sense of how hard it is to describe this thing, but that’s what makes it so good. For a start, it taught me about the actual ‘three-body problem’. There’s also a building sense of metaphysical horror right from the start, which is acute and deeply felt, that the universe may not be scientifically observable. The sequences inside the ‘Three Body’ video game are memorable even though they should be tedious, the use of nano material as a weapon made me wince in pain, and the ending sets up an epic confrontation to follow in subsequent books. If you enjoy science fiction, don’t delay. And if you’re still unsure, Barack Obama provides the endorsement on the cover of the English edition.

Non-Fiction

I have a feeling that nobody reads this for the non-fiction recommendations. This year, a lot of my non-fiction brain was taken up with Tocqueville’s 1835/40 Democracy in America (originally published in two volumes) which is fairly… long. It’s good – Tocqueville is famously perceptive – but it’s not a quick read with a single theme, and you should absolutely form your opinions of Tocqueville from a deeper analysis than a paragraph or two on a blog. That said, everything he says about the power of judges and lawyers in the United States is ferociously on-point, as is his conclusion to the first volume which reads like a movie trailer for the Cold War a century later. In the second volume, Tocqueville also warns of the emergence of a new, business-driven “industrial aristocracy” and then a dangerous form of political stagnation, where a “state of restless agitation [in] the sphere of small domestic concerns” effectively shuts down any developments in the public sphere until it’s too late. There’s a reason that people on all sides of politics still read and admire Tocqueville.

Tocqueville and Democracy in America form one of the chapters in David Runciman’s Confronting Leviathan, which tells a story about the modern state in twelve parts from Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651) to Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man (1992). Reading this was actually a bit of a cheat, because it’s essentially just the printed version of the first series of Runciman’s Talking Politics: History of Ideas podcast from 2020. I loved that series, and still remember a lot of it, so going through it again in book form was just an excuse for me to relive an old pleasure. I have no idea how easy this book would be to follow if you were coming to it fresh, but somebody should try it out and let me know! TLDR: everything in politics comes back to Hobbes.

I also read Michael Taylor’s The Interest, which is a little weird to write about since Michael was a friend at uni. Thankfully, it’s a really good book about the abolition of slavery, or – as more accurately given by the subtitle – “how the British establishment resisted the abolition of slavery”. Michael states plainly at the beginning that he’s trying to tell the capital-P British Politics story of elected officials, newspapers and lobbyists rather than a wider, far-reaching narrative of the transatlantic slave trade which couldn’t possibly fit a book this size. Seen through that lens, this is a revealing and searing examination of how exactly the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 came to be, and the gargantuan amounts of money involved in payments for slave-owners.

Reading Hans van de Ven’s China at War was basically a mistake. It’s a great book, I’m sure, but required too much existing historical knowledge about China – which I don’t have – to make this blow-by-blow account of the varying Nationalist and Communist fortunes between 1937 and 1949 stick. Mostly I’ve just learnt that I need to read another book about China. Adam Tooze’s Shutdown, on the other hand, is obviously a much easier read when you’re still living through the pandemic history he describes. The main takeaway here was to confirm that we all got really, really lucky when Trump nominated Jerome Powell to the Federal Reserve.

The first non-fiction book I read this year was Bill Bryson’s The Body. Most of the detail hasn’t stuck with me, but I do remember it as a typically entertaining, rollicking guide through human biology from a reliable guide – and that a great majority of us are probably suffering from some vitamin D deficiency. Finally, I ended the year with Steve Richards’s The Prime Ministers We Never Had which was a Secret Santa gift from Tash. This is a fascinating tour through the careers of ten (technically eleven, since he lumps the poor Milibands together) almost-Prime Ministers including Rab Butler, Barbara Castle, Michael Portillo and Jeremy Corbyn.

The chapter on Ken Clarke is an interesting reminder of how Thatcherite he was, while honestly I think Michael Heseltine comes out the best as a lost opportunity for the country, at least from the Conservative side. But you’ve got to love Barbara Castle, who not only set up the Overseas Development ministry (shades of Elizabeth Warren here) but later, as Minister for Transport, introduced both speed limits and breathalyser tests for motorists – saving countless lives at a real personal cost to her in terms of the death threats she received. I’d pick quite a few of these options over the Prime Ministers we actually got.