Thanks to beauty of Goodreads, here’s what I’ve read in 2012:

I immensely enjoyed reading The Remains of the Day – my first book of 2012 – but regard it even more highly now, as both the themes and Ishiguro’s beautiful writing style have stuck with me throughout the year. Coraline and The Metamorphosis were both short, creepy and chilling, but some of the longer novels I’ve read this year were disappointing, especially when compared to other works by the same authors. The Time Machine isn’t as good as The First Men In The Moon, despite being more famous, and The Magic Toyshop felt like it was written before Carter really got into her stride.

The big exception to this in 2012 was Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? – easily the best thing I’ve read by Philip K Dick, whose book VALIS (think ‘William Blake in space’) still makes me shudder to think about. I was also a fan of Frankenstein – more so than I expected – while PG Wodehouse remains a reliable delight if you need cheering up (which particular Jeeves novel I happened to pick off a virtual shelf doesn’t seem to really matter much). Special mentions also go to The Hunger Games trilogy, which I am not ashamed to say I wolfed down with great pleasure, and Zadie Smith’s NW – because there’s something special about the one writer who most conjures up real feelings of home.

Non-fiction wise, the stand-out book was clearly Ben Goldacre’s Bad Pharma. I am deeply in awe of this man, and his devastating critique of modern medicine is so much more compelling for providing straightforward, inexpensive and entirely achievable remedies. If nothing else, this is a brilliant demonstration of how to make a sustained evidence-based argument, and I hope Ben has more campaigning success in 2013.

Go on, give me something else to read…

If you want a tedious dawdle around banal philosophy, followed by some actually-rather-gripping boy vs. tiger action… read The Life Of Pi. (Or go see the film, I guess.)

If you want to learn a lot about whales… read Moby Dick.

If you have a lot of time to spare and are insatiably interested in eighteenth century political theory… read The Spirit of the Laws. (Or go see the film. Apparently they’ve added a love interest.)

If you’re planning a 70s-themed sex party… read The Dice Man.

If you’re a proud Tube nerd… read Underground, Overground.

So this is an experiment, inspired entirely by watching Tash this morning, at reviewing the books I’ve read during 2011 so far. My tastes are perhaps rather eccentric, so this may not be of much interest to anyone, but let’s give it a whirl. After all, since there are way too many interesting books to read in the world today, and far too little time to read anything at all, perhaps you can treat reading this review as sorta equivalent to actually having read these yourselves? Maybe?

Also, I’m putting off tidying my floor.

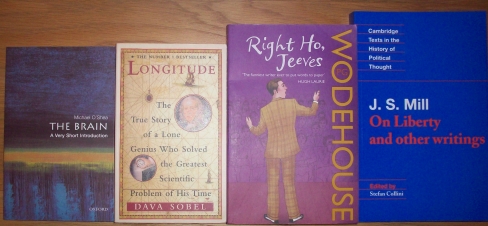

The Brain; Longitude; Right Ho, Jeeves; On Liberty and other writings

I’m rather addicted to the Very Short Introduction series even though I remember little of the detail after finishing, and thus the attempt to be more scientifically literate doesn’t always progress much. Still, the brain is fascinating enough to read about repeatedly, and this book helpfully devotes a decent chunk of time just trying to establish the basics of how neurons actually work. Frustratingly, of course, some of the bigger questions about how consciousness as a whole physically comes about remain largely unanswered, and I very much hope that I’ll be able to read an updated edition in 50 years’ time summarising our further leaps in understanding. In the meantime, this is a primer to the usual high standards of the Very Short Introductions, although not quite as ‘fun’ as the still-extraordinary Phantoms in the Brain. And you know you’re in safe hands with a book which stridently sets out the ‘purely material terms’ of the discussion in the very first paragraph: no messing about with spirituality here.

Longitude – Dava Sobel

I read this as part of my quest to finally get through some books which have been sitting on my shelf for years. The story of eighteenth century clockmaker John Harrison and his life’s work building clocks accurate enough to determine longitude at sea, its greatest attribute is stimulating an appreciation of just how many people in the past worked their little socks off in cumulatively bringing us to where we are today. I mean, this guy really did care about his clocks, and hats off to him for that. The tone is breezy and easy to read – certainly no bad thing – although the narrative quest for heroes and villains does result in a number of people trotted out to be the ‘bad guys’, thwarting our ‘lone genius’ out of jealousy or contempt or bitterness, who unfortunately don’t seem capable of much more serious villainy than perhaps keeping his clock in the sun for too long. Still, sometime it’s nice to read history on a human-scale, and this book won’t demand much of your time in return for making you a lot more knowledgeable about sea clocks.

Right Ho, Jeeves – P.G. Wodehouse

Sublime. I’d never read any Wodehouse before, nor seen any adaptations, but this has instantly converted me into a fan. I sense that some people are turned off by a book set entirely in an inter-war bubble of insufferably posh idiots. Wodehouse is consistently mocking, of course, but it’s certainly very ‘gentle’ (as my dad said a little dismissively) and inclined to leave you walking around for days muttering ‘tush!’ and ‘what ho!’ at the earliest opportunity. Is this inculcating a romantic attachment to a pretty unattractive world of, as previously mentioned, insufferably posh idiots? No, it isn’t. It’s just funny, OK? Beautifully written, wonderfully unstated and hilarious… give it a try, and leave the searing social critique for some other writer in some other book. Right ho, Jeeves!

On Liberty and other writings – J.S. Mill

Toby Young makes a habit of saying ridiculous things, but one of his more outlandish theories revolves around the learning of Latin being necessary because it ‘teaches you to think’ and ‘argue logically’ and ‘swim 200 metres backstroke’ and so on. It’s a shame, not only because it demeans Latin, but also because it implies that English is somehow deficient as a language of serious thought. Reading J.S. Mill might cure him of this illusion. There are three works included here: ‘On Liberty’ (1859), ‘The Subjection of Women’ (1869) and his posthumous drafts of ‘Chapters on Socialism’. Mill was progressive enough to render him immediately likeable to a modern audience, even if you don’t agree with everything he says, and his writing style smacks of a fair-minded consideration of the arguments melded together with passionate force in articulating what he believes. (The defence of freedom of speech in ‘On Liberty’ is particularly good.) I found the final ‘Chapters on Socialism’ the most interesting, actually, mostly because I think they would pass the ‘Saoirse test’: a discussion thoughtful enough not to prompt a metaphorical shot to the head. It was the following line from ‘On Liberty’, however, which had me beaming with nerdy political thought love:

“It is a piece of idle sentimentality that truth, merely as truth, has any inherent power denied to error, of prevailing against the dungeon and the stake.”

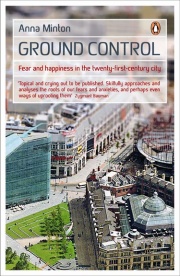

Ground Control

At the request of Esmaa Self, Twitter friend with an obviously cool surname, I thought I’d do a little review of Ground Control by Anna Minton. The book is about the social and psychological impact of British city and housing design, a topic which – to anyone who’s heard me go on about how nice the centre of Leeds is without cars – is clearly a topic close to my heart. It’s also an unabashed polemic against privatisation, the decline of local democracy and British attitudes towards shared spaces and crime.

Divided into three parts, the first – ‘The City’ – deals with the creeping privitisation of large areas of formerly public land in cities, to be policed and controlled by private security firms with their own rules about what behaviour is acceptable within. ‘The Home’ attacks the growth of gated communities and ‘defensible space’, which acts to increase fear of crime as well as strangers in general, robbing cities of the natural protection afforded by strangers in public places. It also lays into the termination of new social housebuilding under Thatcher, and the community-displacing regeneration projects of more recent years. Finally, ‘Civil Society’ challenges the idea that anti-social behaviour is at the root of further crime, arguing that policies such as Blair’s ‘Respect’ agenda are counter-productive in attempting to institutionalise that which can only ever really be provided organically by local communities.

I’m in two minds about this book, and although overall it is well deserving of being read, I’ll start with the negatives in order to end on the high which it deserves. Firstly: it’s perhaps obvious that this is the first full length book from a successful journalist, as there is sometimes an odd pacing which betrays a determination not to go for more than a couple of pages before repeating the central argument of the piece. (She also misuses the word ‘ironically’. Frequently.) More seriously, I’m wary of international comparisons which fall into the oft-repeated technique of reducing the US to wild freemarketism and ‘nice’ continental Europe. Consider the following:

“This is a very European way to enjoy life, window shopping, wandering around, doing nothing, going to the market, taking in the café society of the continental squares and piazzas… rather than spending our way out of recession, we need to look at real alternatives, based on a more European rather than American model, which will moderate the architecture of extreme capitalism…”

Really, though? Europe has one homogeneous model, stretching right across the continent? And before we write off America, shouldn’t we remember that this is the same country which maintains a ginormous system of National Parks? I’m not saying there’s nothing at all in the comparison, but it’s become such a trope that I’d like a little more nuance and case study rather than resorting to ‘Europe’ and ‘America’. Furthermore, it’s a dangerous path to go down, because if you associate ‘markets’ with ‘America’ (i.e. one side of a binary divide) then you lose the ability to suggest workable market mechanisms by which a different culture might be achieved. It is all very well suggesting that there is massive market failure in planning and housing – there is – but that doesn’t mean that the state cannot alter economic incentives in order to change things.

However, this shouldn’t obscure the fact that I do agree with the majority of Ground Control – its central arguments are largely valid, and on an issue which deserves wider public debate. It is important that shopping alone does not come to dominate city centres, and that we retain public, open spaces where citizens are governed by the common rule of law, not private security rules. If we don’t then politics becomes powerless, and so do people. Gated communities in Britain are as vile as they are totally unnecessary. Banning councils from investing ‘Right To Buy’ profits in more social housing was an unqualified policy disaster, fermenting the tensions which we see today being exploited by the likes of the BNP. And, more often than not, it is indeed fear of crime which is a far more debilitating problem than actual crime itself. Segregation by wealth will make both worse.

Minton is very polite, and so never says anything like ‘…and we need thriving British cities, not more suburbia’. So I’m going to say it instead: …and we need thriving British cities, not more suburbia. Suburbia can, of course, inculcate shared public spaces, but does it really have the scale to answer today’s problems? Young people complain that there is nothing to do, the elderly find local services increasingly deemed unsustainable (c.f. the Post Office), whilst everyone needs an alternative to the ghastly reliance on the private car to shuttle back and forwards from place to place without ever really travelling. And aren’t the cities best placed to provide that infrustructure, that diversity, that ‘hustle and bustle’ which Minton euphemistically refers to? A place has got to have more than shopping, but it’s also got to have more than housing plus the odd corner shop. British cities may have their problems, but they’re also worth fighting for, and we abandon them at our peril.

Bad Science

Although I confidentially wrote a mere two blog posts ago about how much I loved book club, a part of me is clearly in a full-scale rebellion against all of that fiction since last week I ordered both Queueing for Beginners and Bad Science in a non-fiction book buying ‘spree’ (albeit not a numerically very impressive one). The former, by Joe Moran, was actually set for my final essay last term and is just a huge amount of fun, so it should be good to have around in the unlikely event that somebody comes running to me demanding to know more about the history of everyday life. But Bad Science, by Ben Goldacre, is a more important and thus even more wonderful book.

The Bad Science ‘brand’ has actually been around for a while, most prominently as a column in the Guardian, and it’s well worth looking at its own website for more. Essentially, Ben Goldacre is a doctor who devotes some of his life to exposing and debunking a few examples from the vast world of journalistic rubbish written about science, and health in particular. The book is designed to ‘help everyone become a more effective bullshit detector’ (according to the nice quote on the front) and it helpfully outlines everything you need to know to investigate ‘scientific’ claims for yourself. Sadly, it’s also the kind of book which I read – think “but I knew all that!” – and then fail to convince anyone who doesn’t to read it or take it seriously. *sigh*

(It also seems deeply and unsettlingly ironic that now two of my favourite books, The Rebel Sell and Bad Science, tackle psychological issues, logical fallacies and general reasons why people believe strange and untrue things, and of course confirmation bias – or picking out things which agree with what you already believe – is top of the list. But oh no! Isn’t that exactly what I’m doing? I certainly can’t deny that reading things which cleverly and wittily argue things I already believe makes me happy. And whilst it is really annoying when people conceive of great conspiracy theories which they alone can perceive – MMR will kill me! Everyone is so conformist and doesn’t think for themselves! – does being ‘one of the few’ (ahem) to debunk those ideas morph into being exactly the same thing? Argh! The perils!)

But seriously, Bad Science touches me deeply because it taps into one of the things I find most depressing of all in the world: attitudes to science. And I say this in the position of not being a scientist myself. I’m hugely ignorant about (statistically speaking) around 100% of how things work, and so are most people. But so what? Just because you don’t understand any one particular scientific theory, why does that have to impair an understanding of science itself – which is, I try to say again and again and again, a method, not a body of facts. Science is so often accused of being:

(a) boring

(b) closed-minded

(c) complicated

which I just utterly fail to understand. To take them one by one:

(a) scientific explanations are invariably more interesting than any ‘alternatives’. As Bad Science notes along with many other people, evolution is just simply a more interesting thing than creationism. The placebo effect is so, so much cooler than rubbish like homoeopathy. In fact, why people believe homoeopathy in the first place is vastly more interesting than homoeopathy.

(b) science is the only system of knowledge acquisition I can think of which is not just perpetually changing but has perpetual change built right in. Any theory can be toppled with enough evidence, and the real business of science is lots of human, utterly fallible scientists all shouting and disagreeing with each other. For some entirely inexplicable reason, this is ‘closed-minded’.

(c) when someone asks me to fix their computer, I tend to keep everything the same apart from one thing which is changed. So if the ‘Internet isn’t working’, you don’t buy a new router and network adaptor, reinstall Windows and switch broadband providers all in one go and then see if it works again. Obviously. I was taught to try and keep all variables bar one the same in something like Year 4, and surely that’s just common sense anyway. And science should make sense most of the time, since it’s only trying to describe the same real world that we all live in. Even when it initially seems counterintuitive, it shouldn’t be too hard to see beyond that. After all, just about everyone in the world has marvelled over the optical illusion where one line looks longer than the other, and people don’t walk away from that confused.

Anyway. Just read the book ![]()

(And finally, in the interests of showing that science is not about the inevitable fallacies of individual scientists, here’s one paragraph from the book which, to quote the sensible person who noted it, “commits many of the sins he spends a whole book castigating bad reporters of science about in just one paragraph”.)