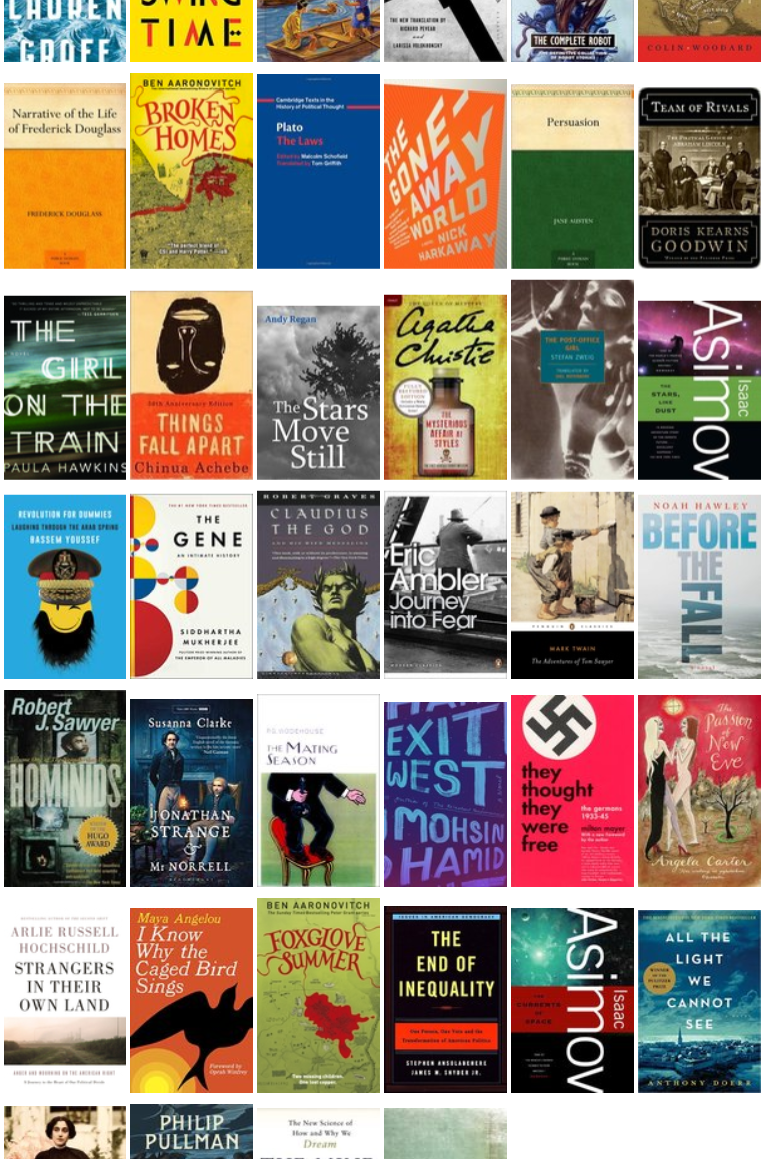

I read a record 40 books in 2017! In an exciting innovation this year, one of these books – The Stars Move Still – was written by my uncle. It’s a fictionalised portrayal of a forgotten American tragedy, and you can buy it now. Let’s take a look at some of the others…

Fiction

As is apparently traditional, I kicked off the year with a gift from Todd: Fates & Furies, two very different perspectives on one marriage which really does make you flip back and re-read sections again in a new light. I was also excited to read Zadie Smith’s new novel, Swing Time, although I found myself much more interested in the central relationship between the narrator and her childhood friend Tracey than the subplot with popstar Aimee.

Early on in the year I also ploughed through The Idiot – it’s only taken me a decade since Mr. Drummond first told me to read it during A-Level history class – and my main takeaway is that Lizaveta Prokofyevna is amazing. I absolutely love her outbursts, and she is very welcome at my literary dinner party. The book is also noteworthy for its discussion on criminality and liberalism, which could easily be written today. It was equally striking to find the actual terms ‘feminism’ and ‘human rights’ in Howards End (from 1910) although the plot and characters were not hugely compelling.

This year I continued my quest through Asimov’s interconnected series, starting with Susan Calvin origin stories in The Complete Robot (along with other memorable robot tales) and continuing through his Galactic Empire books. They are always enjoyable! I also read another two instalments in the Peter Grant series, Broken Homes (a big twist of an ending!) and Foxglove Summer (a detour into the countryside). It’s been a much longer gap since I last read anything from the His Dark Materials universe, but La Belle Sauvage – the first in a new trilogy – was a joy. The story is small in scope, but a confident return to the world of dæmons and Dust.

Abbi’s sci-fi recommendation, The Gone-Away World, was a post-apocalyptic wild ride with definite shades of Vonnegut. Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, which had sat forebodingly on my to-read list for a while, is a giant tome but with an incredible premise and story. Susanna Clarke crafts a compelling alternative history of England divided between Northern and Southern kings, with a lot of folklore, huge attention to historical detail and magic which is beautifully integrated into the world.

However, my favourite piece of speculative fiction this year was Hominids – a story about a Neanderthal man who accidentally crosses over from a parallel universe in which Neanderthals survived rather than humans. I feel a little guilty naming this as my favourite because as a work of literature it is definitely not the best. There’s a definite ‘genre sci-fi’ feel where interesting ideas and discussions take precedence over plots or characters, not to mention a clumsy rape scene which is not handled well. Despite all of this, I just really really wanted the whole thing to be true so that I could talk to a Neanderthal. The impact of small biological differences between the two species, such as a stronger Neanderthal sense of smell, are fascinating when the author imagines how their civilisation would differ as a result. And it left me feeling a bit bad about being a homo sapien. I will never use ‘neanderthal’ as an insult again.

I am pathetically bad at predicting where a plot is going to go, so it was exciting to be able to read The Girl on the Train and work out the killer for myself, albeit taking 70% of the book to get there. Eric Ambler’s Journey Into Fear was another straightforward thriller, and super enjoyable. Before The Fall was also a compulsive read, piecing together the mystery behind a plane crash, although the ending was a little anti-climactic as various open plot threads and red herrings were left hanging open.

I confess that I only made a note to read Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglas after Trump memorably said he was doing an ‘amazing job’, but everyone should take the time to read this searing first-hand account of American slavery. To continue the theme of reading good books for bad reasons: I was spurred into reading Maya Angelou’s I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings by a 1-star Goodreads review in which the mother of a 15-year old boy objects to the ‘sordid details’ he is ‘forced’ to read about for school. She finally compromises by telling him ‘which chapters to skip’. I guess I owe this woman something, because I deeply appreciated reading and learning more about Angelou’s amazing life, which I hadn’t realised the book was so closely based on.

Growing up in the UK I was never ‘forced’ to read American classic The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, but I did so under my own free will this year and enjoyed it once the action picked up. The Passion of New Eve was a blast of Angela Carter: violent and sexual and liable to fuel the flames depending on how you see it. My mum suggested The Post-Office Girl, full of vivid descriptions of places and characters, and by the end I was quite keen to see whether the heroes would be able to pull off their crime or not. Exit West is a (somewhat obvious) metaphor for the era of global migration we are living through, but I actually found the birth and death of a relationship to be the most moving part. Finally, All The Light We Cannot See was a beautifully written and fast-paced intertwined story of a blind French girl and a German boy during World War Two. It made me sad about Brexit all over again.

Non-Fiction

The only American history I ever studied was all post-Civil War, and so I found American Nations to be incredibly helpful in understanding how the United States was first put together. I had no idea that the slave system of the Deep South migrated from Barbados, for example, or the sharp distinctions between the New England Puritans and the Virginian gentry which can be traced back to the English Civil War. Meanwhile, it is easy to forget the Spanish settlements in Florida and New Mexico which get lost in all of the ‘East to West’ narrative. I am sure you can quibble with exactly how Woodard carves up the country, but overall I have a much better grasp of its distinct cultures and histories.

Jumping forward in time to Lincoln, Team of Rivals – which took me a month to get through – is a very detailed account of his rise to the Presidency together with his leading competitors. It was well worth reading although I was expecting a little more historiography along with the narrative, and I still have some unanswered questions. For example, was Lincoln actually any good as a war leader? The Civil War certainly reads like a series of military disasters in the beginning, although perhaps the whole government would have disintegrated under anyone else.

Rounding out the American history, I also read The End of Inequality, a click-bait title for what is actually a fairly dry piece of academia on the (genuinely fascinating) 1962 Baker vs. Carr decision. Save yourself some time and listen to the More Perfect episode instead. I am also down on this book because in the last few pages they become fabulously stupid and wrong about international solutions to gerrymandering.

If you want a chillingly relevant insight into the ‘anti-politics’ mood, They Thought They Were Free is based on interviews with ten ordinary Nazis from a quiet, non-industrial German town conducted right after the Second World War. Similarly, not because they are Nazis but for a a comparable bottom-up perspective of the modern American right, I highly recommend Strangers In Their Own Land. Arlie Hochschild, a sociologist from Berkeley, does an excellent job talking to conservative voters from rural Louisiana, and smartly uses the issue of local environmental damage (from which these people suffer a great deal) to probe the question of why they continue to oppose any government protection or regulation.

Finally, if you want to panic about a different social nightmare, read The Gene by Siddhartha Mukherjee. As with his previous book on cancer, The Emperor Of All Maladies, this is a fascinating and informative exploration of the history and science of genetics. But I came away with a terrible sinking feeling about where genetic engineering is going to lead us. Alternative, there’s always the equally dark world of Plato’s The Laws, in which Plato (a) sneakily tries to make his own book compulsory reading material, (b) bans discounting (thanks, dude) and (c) limits his city’s population to 5040 citizens exactly. Good luck with that.

Allison Norman, Arpan Sinha, Jason Zhou liked this post.