Like the stock market bubble, the expected implosion of my reading total was staved off this year. In fact, I managed 26 books in total, which is four more than last year! For this I have to credit both our holiday in China and a golden two-week paternity leave which involved a lot of ‘sitting on the sofa next to a sleeping baby’ time. Since neither of these factors will recur next year, I’m still expecting my reading to drop off a cliff for 2026.

Oh, and on a non-book note, this year I also experimented with reading on a new Kobo Libra, rather than my Kindle, in addition to physical books. It’s really nice to have colour covers on an e-reader, even at the cost of some black-and-white crispness, and for some reason Amazon have decided they can’t be bothered to make a device with physical page turn buttons anymore. Also, it’s reassuring to confirm that my reading library works seamlessly between devices, rather than being tethered to one company. So, I’ve been very happy with that change too, even though the truly ‘perfect’ e-reader has still yet to be made.

Fiction

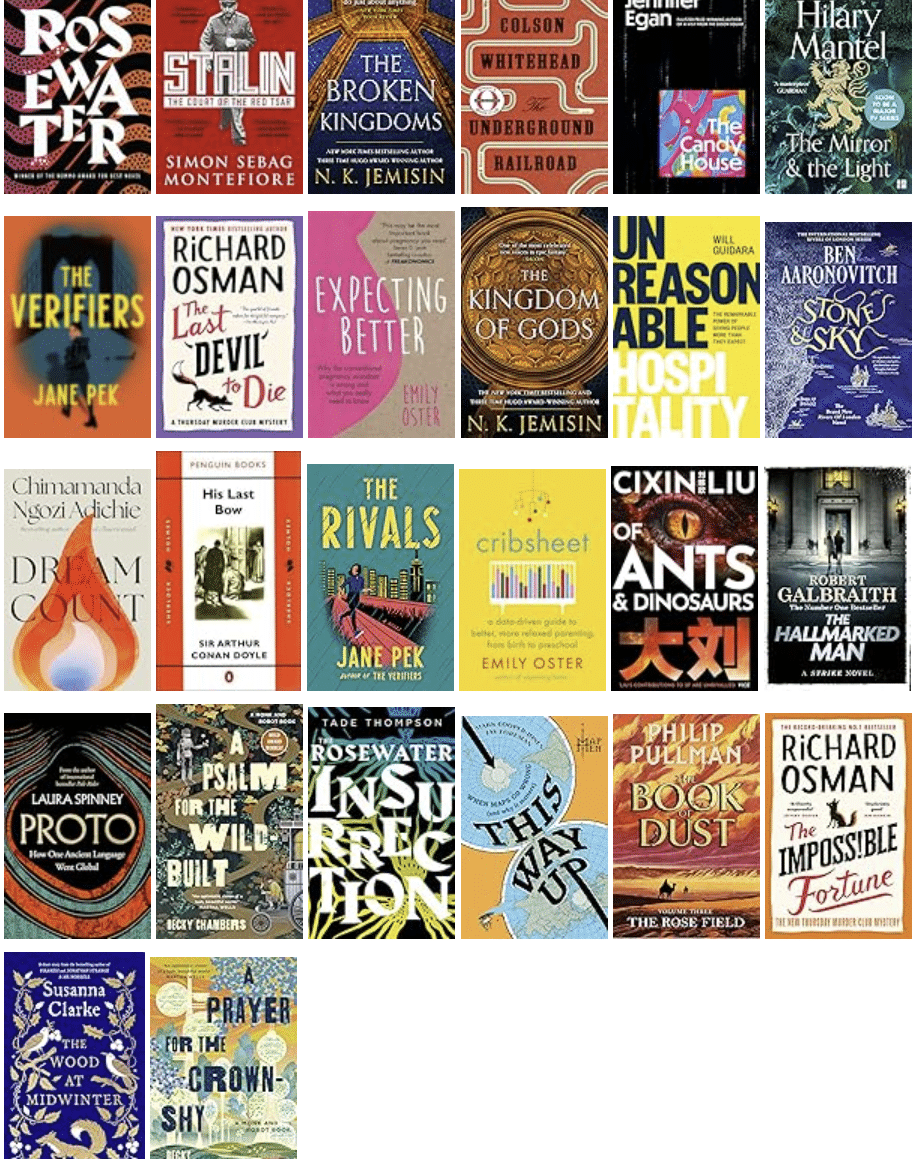

I kicked off the year with Tade Thompson’s Rosewater, followed later in the year by its sequel The Rosewater Insurrection. Set in the 2050s, this trilogy belongs firmly to the ‘alien invasion’ sci-fi subgenre and is centred around a giant, mysterious biodome which emerges suddenly in the Nigerian town of Rosewater. Thanks to the dome’s miraculous healing powers, Rosewater quickly becomes a major site of pilgrimage and begins to assert its independence from Nigeria itself.

In Rosewater, the creeping sense that humanity has already lost to the aliens from the very beginning, despite the invasion’s slow build-up, had strong echoes of The Three-Body Problem, although the style is very different. In the second book, the focus shifts to the mayor’s attempt to formally declare independence from Nigeria. Can the citizens of Rosewater broker a mutually beneficial compromise with the malevolent alien Wormwood against their common enemies? Overall, this was a good first choice for the year, and I’m looking forward to concluding the trilogy in 2026!

Speaking of Cixin Liu, I also really enjoyed Of Ants and Dinosaurs, a short little fable which I borrowed from Katie and read in a few sittings. It’s a wry parable of Cold War-esque paranoia and the terrible logic of mutually assured destruction, with ants and dinosaurs alternating between beneficial collaboration and fierce confrontation. As always with Liu, you also get the sense that he just really, really enjoys figuring out the intricate military details of how exactly the armies of ants are able to wage their wars on dinosaurs, and vice versa. And to be fair, these little details make for a very fun read. Highly recommended!

A series I completed in 2025 was NK Jemisin’s Inheritance Trilogy, completing both The Broken Kingdoms and The Kingdom of Gods. (Yes, if it wasn’t obvious, many of my reading choices this year were made because I wanted to tie up loose ends before having a child!) Overall, I still didn’t love this series, and although the second book showed signs of improvement, these fell away again in the last one. Perhaps the central problem is that having ‘gods’ as protagonists just doesn’t work for me, for reasons not unrelated to why ‘gods’ don’t work for me as a general concept. It feels as if there are no rules, and so nothing really makes sense, because although the gods have Aristotelian ‘purposes’ (which is dumb) there’s no real drama or tension.

It figures, then, that The Broken Kingdoms stood out from the pack for being written from the perspective of a human (a woman named Oree, who is blind but has the ability to see magic) and was about her relationship with ‘Shiny’, i.e. the sun god Itempas made mortal. I also remember my favourite scenes were the ones in which the true terror of Nahadoth, the god of darkness, was made clear. But overall I’m relieved to be done with this trilogy so that I can move on to fresh NK Jemisin worlds.

I hate to say this, but I also have some disappointment around Philip Pullman’s The Rose Field, the concluding part of ‘The Book of Dust’ series which extends the ‘His Dark Materials’ trilogy which I grew up loving. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a major improvement on 2019’s The Secret Commonwealth. We finally get the brave, adventurous Lyra back after the unhappy breakdown of her relationship with Pan, which never really made any sense. And it’s certainly a rollicking journey to the mysterious ‘red building’ in the Karamakan desert, far to the east. A particularly wonderful highlight of the book is Lyra’s encounter with Mustafa Bey – a Turkish merchant whose trading empire stretches far along the Silk Road – in a café in Aleppo. It’s just beautifully written.

Overall, though, the issue is that once Lyra finally reaches her destination there are just so many questions left unanswered. A nicer way of saying this, to borrow from Reddit, is that the ending is “quiet”, which is true. And of course, I wouldn’t expect – or hope – for everything to be wrapped up with a bow. But everything from Lyra’s relationship with Malcolm (heavily built up, then suddenly tossed aside) to fundamental bedrock questions of the series (are the gaps between worlds a mortal danger to us, worthy of great sacrifice to close, or actually… good?) are just kinda left hanging in the air.

At my grandmother’s funeral this month, to illustrate the idea of an eternal afterlife, the vicar used the image of an author writing a book, of which only a single copy is produced and later destroyed. While the particular book is gone, the story is “not really lost” because it emerged from the mind of its author, and so could do so again. And so it is between humans and god. (“It’s not a perfect analogy.”) The obvious, gaping fallacy here, of course, is that an author obviously couldn’t write the same book again, because any work of art is not the product of a static, unchanging mind but a very particular result of particular conditions at one moment in time.

Pullman, naturally, would see right through this shallow theology. But I bring it up because it reminded me of the relationship between his two series. They may share the same author’s name on the cover. But the sparkling magic of ‘His Dark Materials’ can’t simply be reignited decades later, even if its slow-burning afterglow remains a very warm and happy place to be.

Another series which I managed to finish this year was Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy, which concludes with The Mirror & the Light. This series hasn’t always been an easy read, but I’ve definitely enjoyed each book more than the last. There’s an especially chilling moment in this one – about a third of the way in – when a false rumour spreads about Cromwell’s plan to marry the King’s daughter Mary, and you suddenly start to sense the wheel of fortune turn for this masterful operator. Later, when the King admits to Cromwell that he no longer finds him surprising, and misses Cardinal Wolsey, you feel the floor fall away beneath him. The end comes not long after, accelerated by a disastrous marriage to Anne of Cleves and foreign interests plotting to undermine England’s great politician. (Special thanks to the Redditors who posted their chapter-by-chapter analyses in readalong threads – this made the book much more rewarding to read!)

The Underground Railroad had sat on my to-read list for a long time, and ultimately proved both very easy and very difficult to get through. The prose is nimble and light, but the underlying subject matter – escaping plantation slavery in the American South – is always horrifying. For obvious reasons, I did love the central image of a literal underground railroad, which (smartly) only appears at fleeting moments in the book.

I loved The Candy House, Jennifer Egan’s sequel to A Visit from the Goon Squad. It’s written in the same short-story style, but this time set a little in the future and featuring many of the children of the original cast of characters. I just wish I had a better memory for it all. Honestly, I struggled to keep straight in my head all the interlinked plots and characters from this book while I was reading it, let alone remember how they all fit together with the original. Thankfully, somebody has made a useful character map (here’s a mirror for UK readers) but what I really need is a big visual guide to the two books combined!

Any new Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie novel is something to treasure, so I was very excited when Dream Count came out this year. In the past I’ve always preferred her books set in Nigeria to the US, but this one splits the difference as it moves between the perspectives of four women – Chiamaka, Zikora, Omelogor and Kadiatou – and between Nigeria, the US and rural Guinea. The writing is always superb, and can’t fail to draw you in. It’s the most heartbreaking moments which stuck with me: Zikora’s abandonment during her pregnancy, the diminishment of the bold and brash Omelogor in America’s smug academic culture, and the awful trauma suffered by Kadiatou. But there are a lot of lighter parts, too. Strongly recommended, as always.

The Hallmarked Man was the latest entry in the Cormoran Strike series, and I thought it was a good one! The core plot was maybe not as innovative as the previous two books, but its resolution felt much more satisfying and cohesive, which is a major improvement. More importantly, absolutely nobody is still reading these books for the murders anyway: it’s all about Robin and Strike, and the writing is even more explicitly structured around this now.

Strike definitely comes across as a total dick: constantly scheming to separate Robin from her perfectly lovely boyfriend Ryan. I did feel it was a bit of a cheap plot device to have Ryan (a recovering alcoholic) relapse, since it then softens the more interesting dilemma of whether Robin should stay with him or not. But hey, we finally get a finale with the big confrontation we’ve all been waiting for, and I loved the surprise (but very amusing) role for Pat at the very end.

More entries in continuing series included Stone & Sky, the latest ‘Rivers of London’ installment, or “the one with the mermaid”! Set in Aberdeen, I enjoyed the alternating narrations between Peter and Abigail, although at this point I feel like Abigail comes across as the stronger character. Meanwhile, down at Coopers Chase, I read both The Last Devil to Die and The Impossible Fortune. The emotional core of the former book is Stephen’s deepening dementia, while in the latter Elizabeth is starting to put her life together again. This storyline really helped to soften the most annoying drawback of the series for me, i.e. the glib entitlement of the retirees. Relatedly, Joanna is now my absolute favourite character for finally standing up to Elizabeth. (Oh, and Ron’s grandson Kendrick’s crush on Tia is absolutely adorable.)

You can tell that Arthur Conan Doyle had realised that his usual Sherlock Holmes formula had pretty much been exhausted by the time of His Last Bow, because some of the stories in this collection are pleasingly experimental, such as the expanded role for Mycroft Holmes in ‘The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans’. My favourite was ‘The Adventure of the Red Circle’ because reading it aloud (a staple Domdi evening activity) provided the opportunity for lots of silly accents. Most unusual is the final story, ‘His Last Bow’. Written in 1917, this is an amusing reunion of an ageing Holmes and Watson to foil a German spy. There’s no detective mystery to unravel at all here, it’s just a patriotic contribution to the war effort!

The Wood at Midwinter is a very, very short Christmas story about a saint who wishes for a child and adopts a bear cub. Appropriately, I read it on Christmas Eve. Meanwhile, A Psalm for the Wild-Built and A Prayer for the Crown-Shy is a pair of utopian sci-fi books (the ‘Monk & Robot’ series) from Becky Chambers. It’s set in a post-robot uprising world in which humans have learned to live harmoniously within their natural limits, while the robots originally built for humanity’s factories have retreated into the wild.

A Psalm for the Wild-Built was the first thing I read after our son was born, because I thought I owed him something optimistic for the future. It’s an odd little book. I don’t share the innate pastoralism, but the pairing of Dex (a “tea monk” who travels between villages, making tea and listening to people’s troubles) with Mosscap (a robot who emerges out of the wilderness to check on how humanity has progressed) is really lovely, and clearly a spiritual descendant of Asimov’s Elijah Baley and R. Daneel Olivaw. If I was being critical, I’d say that Ursula Le Guin was much more honest than Chambers about the level of coercion required to make any social system work, even the ones which might seem very attractive.

By a process of elimination, I think I’ve now arrived at my truly favourite reads for 2025: Jane Pek’s The Verifiers and its sequel The Rivals. Huge thanks to Toggolyn for gifting the first one to Randi, which I subsequently borrowed! These books are fun, page-turning thrillers following the life of Claudia Yin, a young New Yorker who loves detective fiction and cycling in inappropriate weather. She joins Veracity, a secretive agency which investigates dodgy online dating profiles on behalf of its clients, and quickly gets drawn into the murky, murderous underbelly of the online matchmaking companies.

The second book loses a point for ending so abruptly on a giant cliffhanger, and in general the biggest weakness of the series is the sheer technical unbelievability of Veracity’s hacking abilities. On the other hand, there’s no need to stop and think about that for too long, thanks partly to the intricate mysteries themselves but also the stresses and strains of Chinese-American immigrant family life. In particular, Claudia’s relationship with her (very tough) mother is a central foundation to the series. But perhaps the best part about the whole thing is Claudia’s love for Inspector Yuan: a fictional detective who, in-universe, is the star of a long-running series set during the Ming Dynasty. I would absolutely read these next if I could, at least while waiting for the third Claudia Lin adventure.

Non-Fiction

Simon Sebag Montefiore has an odd writing style. I wasn’t especially seeking him out, but I was looking for a biography of Stalin and this was well-reviewed, which is how I came to read Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar this year. (Technically this is a follow-up to Young Stalin, but given that there’s a limit to how much Stalin I actually want to consume, it seemed best to prioritise his ruling period.) What initially threw me, although I did eventually get used to it, is that each chapter felt like reading raw writing notes, complete with all the relevant quotes. I was expecting more of a narrative!

That said, by the end I had a clear sense of how the small, petty corruptions of leadership were magnified to such horrific extremes in Stalin’s court. We’re all familiar with the dilemmas: not wanting to contradict the boss, but also not wanting to seem sycophantic. At root these same instincts also underpinned Stalin’s rule, but led to constant, bloody purges rather than poor business decisions or a losing election campaign.

I read and listen to so much about the crumbling of liberal democracy these days, but all political systems have their own weaknesses, and ultimately the cult of personality is not a durable institution. So, in a strange way, this book left me hopeful.

For obvious reasons, Randi and I both read Emily Oster’s data-driven guide to pregnancy Expecting Better this year, plus her follow-up Cribsheet which covers the early years of parenting. These came highly recommended, although Oster is American and so some of the advice isn’t particularly relevant for British parents.

Expecting Better is the better book, and overall very useful. From memory, the most helpful sections were on miscarriage rates by number of weeks (always good to have the raw numbers) and a clear explanation for why certain foods should be avoided, because it’s helpful to actually understand the mechanism in order to properly judge the risk. (For the record, things like mercury and alcohol are actively bad above a certain quantity, whereas the danger from foods such as sushi is purely the risk of food poisoning.)

I found Cribsheet much less helpful. Partly, this is because while we all largely agree on the outcomes we want from pregnancy, raising a child is obviously deeply personal and depends on the individual parents. The empirical outcomes are much harder to measure anyway, which is why so many of the chapters conclude in a vague, open-ended way. But also, Oster is clearly a naturally anxious person, so a lot of the book is just her talking herself into being more relaxed. That’s good for her, but thankfully this isn’t a problem we currently have, and fingers crossed it’s something we can avoid…!

Unreasonable Hospitality was a gift from the nice people at Booking.com, and I don’t have much to say about it other than some stories were clearly lifted directly into The Bear! This Way Up: When Maps Go Wrong was a gift from me to myself, and an absolute delight. Randi and I have been big fans of Jay Foreman and Mark Cooper-Jones’s Map Men series from the very beginning. We’ve even got a Map Men mug! Happily, this book perfectly captures their blend of self-aware humour and, well, super interesting facts about maps. The whole thing is great, but I think my favourite chapter was the one on Google Maps, and the difficulties they faced when expanding to India. (Did you know that 60% of Indian streets don’t have street names? Neither did Google…)

Finally, on a bit of a whim, this year I read Laura Spinney’s Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global. This traces the astonishing spread and development of Proto-Indo-European, the singular ‘ancestor’ language to many modern tongues as diverse as English to Gujarati. I definitely won’t pretend to have taken everything in, but it’s very rare for me to read any history which stretches so far back, and so a little mind-blowing to think about modern humans migrating and communicating long, long before any of our ‘historical’ categories of peoples existed.

It’s a good reminder of how impermanent these constructs really are. I also appreciated Spinney’s reminder that it was only 18th century European nation-state building projects which established the idea that monolingualism was the ‘normal’ state of affairs for a country, and that much of the world just doesn’t work this way. (See also “different places are genuinely different” from This Way Up, as above.)

Since I’m not a linguist, I do struggle to spot the difference between ‘these words are clearly connected’ vs. ‘these words are totally unrelated’ just by looking at mysterious IPA symbols. I was also deeply curious about why it’s worth writing a book about Proto-Indo-European but not its ultimate Proto-Human ancestor. This is briefly discussed but then set aside in the intro, but I was interested to learn more. Is it just impossible to say very much? Why can’t we use the same techniques to extend the ‘family tree’ of languages further back? (I’m sure there are plenty of good answers to these questions… they’re just the ones which occurred to me at the time.)

I’ll leave you with my favourite language fact from Proto: the origin of the English word ‘merry’ (as in, Merry Christmas!) evolved from meaning ‘short’. In other words, people were cheerful when their religious ceremonies didn’t drag on for too long…😉