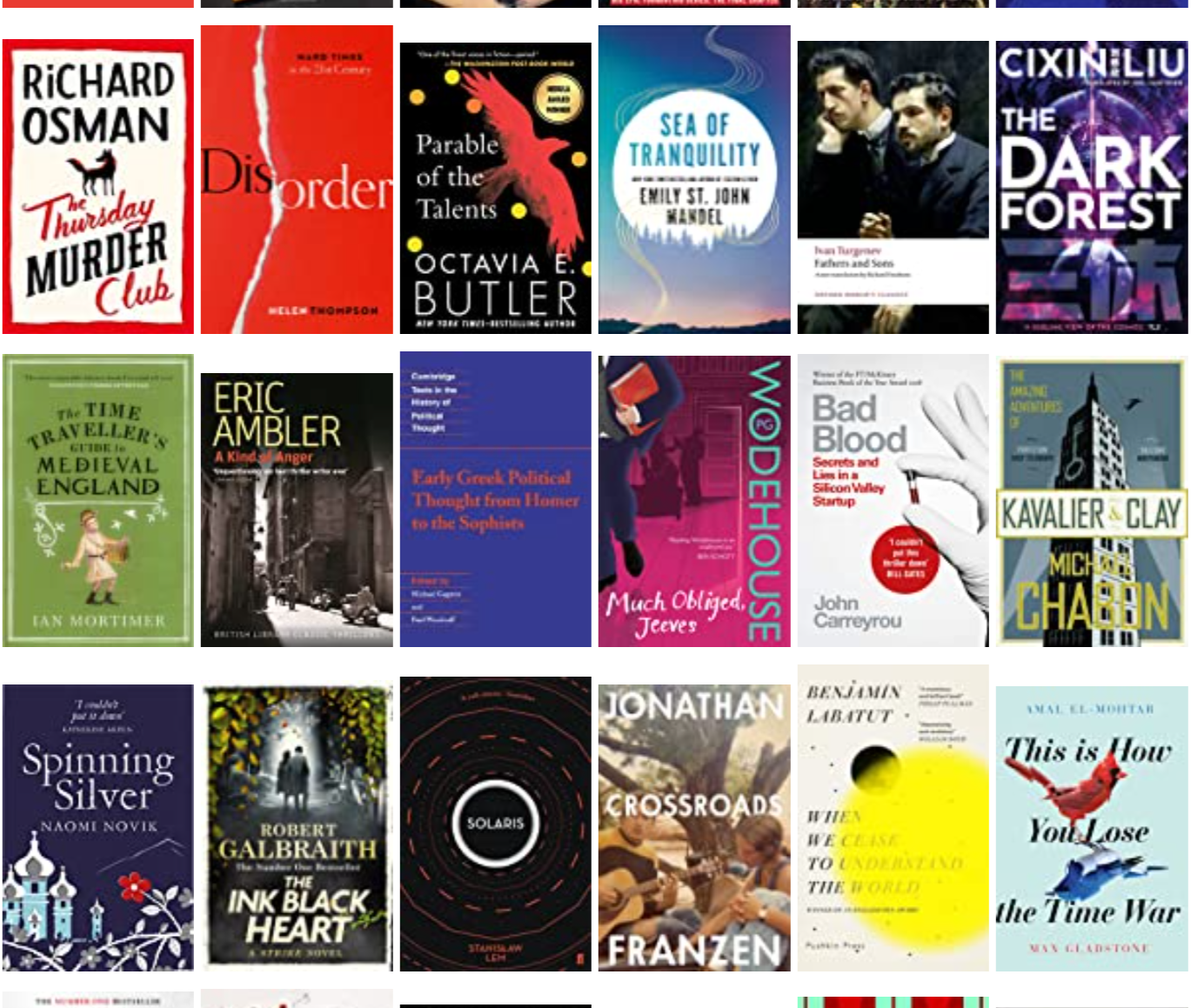

Finally: a (very slight) reversal in fortunes for my reading total! This year I managed 30 books, up from 29 in 2021, and the only thing it cost me was my peace of mind after spending New Year’s Eve immersed in a claustrophobic Gothic thriller. But more on that later…

Fiction

It may be a self-fulfilling prophecy, but once again the first book I read this year – Fatherland, by Robert Harris – turned out to be one of my favourites. First published in 1992, this was Harris’s debut novel and the one which made him famous, no doubt driven by our perpetual collective fascination with Nazi history. Fatherland is a classic of alternative history, set during the 1960s in a victorious Nazi Germany which diverged from our own timeline after 1942. The use of real people and events from our common history until that point makes this imagined world feel chillingly familiar, and the story itself is a captivating detective thriller which, at its heart, is more interested in unearthing the (real) events of the Wannsee Conference than solving a totally fictional mystery.

While my first Robert Harris novel was a hit, my first Jennifer Egan novel – Manhattan Beach – was more of a miss. Indeed, Todd and Carolyn were surprised that this was the one I picked to read, and the book’s promised intrigue was never really parlayed into a strong emotional connection to the characters. For me, the most moving section was when Anna – the first female diver at the Brooklyn Navy Yard – dives successfully for the first time. I had similarly mixed views about The Poisonwood Bible, Barbara Kingsolver’s book about an American missionary family living in the Congo. The fact that the four daughters are a little too cleanly well-defined, bordering on caricatures, made the story easy to follow but less good than it could have been. It also felt like the climax arrives prematurely, with the family’s great disaster and subsequent exodus concluding long before the final page.

One book I did love in 2021 was The Three-Body Problem, and the second book in the trilogy – The Dark Forest – was also incredibly good. I found it slower to get into at first – it took me a month to finish! – but overall Liu Cixin avoids the classic middle-book problem by adding an impressive cocktail of new ideas and concepts. Quick summary: faced with a slow-moving but overpowering invasion force, humanity devises the Wallfacer Project to give four individuals (‘Wallfacers’) incredible unchecked power to work on secret counter-strategies. Added to this are ‘Wallbreaker’ opponents, hibernation into the future and – ultimately – a crushingly dark explanation for the Fermi Paradox from which the book gets its name. I’m so excited for the final installment!

This year I also made a return visit to Octavia Butler’s two-part dystopian ‘Parables’ series for Parable of the Talents. This is relentlessly grim and depressing, with a level of violence which can feel gratuitous and inescapable. Nevertheless, there’s a deep cleverness in how Butler presents Lauren, the original book’s hero, as a delusional cult leader through the retrospective eyes of her daughter Larkin. How are we supposed to feel about Lauren, really? Butler is deliberately ambiguous, but for me I couldn’t shake the feeling that her single-minded dogma might still be basically correct. And if you read the book this way, the final chapter – where humanity finally takes a small, shaky, horribly imperfect step towards Lauren’s spacebound future – is a moment of hope. I was also fascinated by the scraps of information available on Butler’s aborted third book in the series, Parable of the Trickster, which exists only as dozens and dozens of false starts in the archive. Such a tantalising glimpse into what might have been.

Solaris was a gift from Tash and a really interesting book to think about, especially since we know that the author, Stanisław Lem, didn’t think much of the English translation. The basic science-fiction concept of a vast, mysterious, sentient but unknowable ocean planet is compelling, but it can be difficult to keep the pace through the first-person narrative, and the lengthy academic biographies of the Solaristics are very boring. (And yes, I do realise they’re supposed to be.) Once I finished the book, though, I was struck by a rebellious feeling that humanity actually acquits itself rather well. Solaris is partly about the inherent limits to our capacity to understand something truly alien, and the point of the tedious academia is to show that science is – to some extent, anyway – doomed to stumble around in our anthropomorphisms forever. But actually, a lot of the theories and observations made by the scientists feel like they are useful pieces of a puzzle, and do contain some truth, even if a neat and tidy explanation (or mutually satisfying alien ‘contact’) is never reached. So, no need to be so pessimistic!

Sadly, it’s also true that the obvious racism and sexism in Solaris is grating, even if the book still stands up as a whole. Things are less clear for Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall, which bumbles along as a light-hearted social satire (unassuming scholarship student Paul Pennyfeather is kicked out of Oxford after becoming an innocent victim of some drunken toffs, before finding a teaching job at a rundown boarding school) until the appearance of a black character, Chokey, at the school sports day. Repeated use of the n-word follows. I’m not trying to censor the book out of the universe, and – in fact – the ignorance and bigotry of the white characters is partly (but only partly) what’s being lampooned. The point is more that Decline and Fall is supposed to be a comic novel which makes you laugh, but comedy is hard to transplant out of its own time and for a modern reader this whole section is a serious wrench.

The obvious comparison to Waugh is Wodehouse, although he’s much less interested in social critique and more about the comic foibles of individuals. Still, the most memorable moment in Much Obliged, Jeeves – written in 1971, and one of the last Jeeves stories ever told – is when Wooster is persuaded to go canvassing at a general election. Given that these books usually take place in a totally sealed-off pseudo-Edwardian bubble, it was a very strange moment of collision with a more modern world.

If we’re going for controversy, this is probably the moment to say how excited I was for the next book in the Cormoran Strike series – The Ink Black Heart – even as the author’s public persona becomes more and more unpleasant. To state the obvious, this is a review of the book – and not of JK Rowling – which was as engrossing and page-turning as ever. It’s not the best in the series, though, with a few moments which felt fundamentally unbelievable (e.g. Robin’s physical recklessness) and some backpedalling on the central Robin/Strike relationship which seems to reverse some of the progress last time. Moreover, and without giving anything away, I’m still not entirely clear on the villain’s motivations for acting exactly when they do. That said, there are some standout moments – the absolute best is when the tissue of lies around one sympathetic character suddenly falls away and the crushing cruelty of the true situation is exposed.

OK, time for an unambiguously great book: Spinning Silver, by Naomi Novik. This was a birthday gift from Oliver and Abi, but seeing as it features multiple Jewish weddings – including the Hora – it was the perfect book for me to be reading this September. The story is a fairytale about debt and obligation set in a beautifully atmospheric medieval kingdom, and I could almost feel the chill of the frost in the air as I read it. The characters are striking and memorable, and the whole novel is a potent blend between the outright fantastical elements and the Jewishness of the main character, Miryem. Together with Fatherland I guess my winning theme this year was stories set on this borderline, which is also true of Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World. This is a strange one. Self-described as a ‘work of fiction based on real events’ where the ‘quantity of fiction grows throughout the book’, this is a collection of essays / short stories / other things about the inner struggles, torments and ‘genius’ of some great twentieth-century scientists. Weirdly brilliant and fascinating, and maybe best thought of as both fiction and non-fiction much like the wave/particle duality.

I’ve been waiting for the first obvious “book written during Covid-19” and Emily St. John Mandel’s Sea of Tranquility was it. The time-travel concept is not hugely original, but it’s a short story which doesn’t overstay its welcome and I certainly enjoyed it. (Plus I discovered later that one of the timelines is a spinoff from The Glass Hotel, which I haven’t read yet, but am now intrigued about.) A more unusual time-travel book was This Is How You Lose the Time War – nicked excitedly from Katie’s flat – a lyrical and poetic love story which was nothing like what I expected, but in a good way. This style of writing doesn’t always play to my strengths as a reader but I could still admire the beauty even if I don’t linger on the words long enough to truly soak them in. Plus I like to imagine Red & Blue out there in the universe together still, chased but uncaught.

Deep down, I think I always knew that The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay wouldn’t do it for me, in part because the golden era of comic books in 1940s New York doesn’t resonate enough as a backdrop to compensate for the ponderous writing style. I am sure that this is a ‘good book’. But it’s also a long book, and I just didn’t have much to say about it afterwards. (Although now in my head it is melding with Manhattan Beach, which is kinda fun.) A more recent attempted entry into the ‘great American literature’ canon is Jonathan Franzen’s Crossroads, which – as always with Frazen – I found very readable and enjoyable even though I didn’t think it was peak-Franzen. Main complaint: the plots all end a little abruptly, with the final chapter making it seem that the relationship between siblings Clem and Becky was The Defining Theme of the whole novel, which wasn’t what it felt like along the way. Still, this is but the first part of a multi-generational trilogy so I’m sure there will be more to develop, and I’m here for it.

I liked The Thursday Murder Club. I did. I have no snobbish objection whatsoever to Richard Osman writing a series of fun, popular murder mysteries about a group of retirees who solve crimes. My problem is – and I know this makes me a terrible person – I can’t help but get annoyed when old people play the we’re-too-old-to-follow-the-rules schtick. And I know that this objection doesn’t even make sense! There isn’t an ameteur detective of any age in any book who just sits patiently and does what the police tells them – otherwise there wouldn’t be a story! So, I get it. The problem is me. But still, I liked Agatha Christie’s The ABC Murders more. This is her take on the serial killer trope (“basically an episode of Criminal Minds” as one reviewer writes on Goodreads) and it’s all very good and clever and intricately worked out. Ahh you think they’ve figured it out? Ahh but they haven’t yet. But don’t worry, Poirot will save the day.

Forward the Foundation was the very last book published in Asimov’s Foundation series, although it’s a prequel and the last chronological book – Foundation and Earth – is the one which will hold the last word in my mind. A Kind of Anger was exactly what you want from an Eric Ambler Cold War-era spy thriller, and my only worry is that I’m about to run out of Eric Ambler Cold War-era spy thrillers. Fathers and Sons (Turgenev’s Russian classic from 1862) was probably more funk-inducing for me to read than it would have been before my own father died, which added an extra layer of sadness to this (very good) tale of young nihilism and the growing divide between generations.

Amongst Our Weapons was a pretty good entry in the Peter Grant canon, although I agree with the general clamour for more Nightingale to feature in the books again. And then, sure, it’s true I only read The Slow Regard of Silent Things because I didn’t want to totally forget about the Kingkiller Chronicle world as we all wait for the much-delayed-maybe-never-coming third book. The author is at pains to stress, repeatedly, that you probably won’t enjoy reading it because it’s a short character study on Auri – a young woman who lives underground and has a deep bond with inanimate objects – without much of a plot. But I won’t take the bait. I did enjoy it. It was a good character study.

And finally – just in the nick of time – I rounded up this year’s reading to a satisfying total with Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived In the Castle. There’s a spark of electricity running through this Gothic thriller, and the opening hooked me in immediately. Written in the unsettling narration of eighteen year-old Mary Katherine ‘Merricat’ Blackwood, there are dark undercurrents, deception and self-deception behind the mystery of what exactly happened, six years prior, to leave almost all the other Blackwoods dead. Recommended.

Non-Fiction

The first non-fiction book I read this year was Peter Mandler’s The Crisis of the Meritocracy, which has a special place in my heart because (a) he pulled a copy off the shelf to give to me when I went round for tea last year, (b) it sits proudly on my bookshelf next to Melissa Benn’s School Wars. Mandler and Benn have been a double-act in my life for many years now, locked in a perpetual field of agreement and disagreement, but a few months ago they both messaged me separately (within hours of each other… it was really cute) after finally meeting in person, and I felt very happy to have been a small conduit between two of my big education influences.

Anyway – none of that tells you anything about the book, it’s just some personal colour I forgot to include in previous blog posts. Where were we? Ah yes, The Crisis of the Meritocracy, which is a somewhat confusing title for this pretty upbeat, positive story about British mass education since the Second World War. The key move is to take a ‘demand-side’ view, and Mandler’s point is that the country’s population has consistently shown a powerful, democratic desire for more and better education. This pushes elites to respond, often with hesitation and reluctance, despite a perennial fear that we’re just about to bump up against the mythical upper-limit of people who might ‘usefully’ benefit from wider participation. It’s a useful corrective to the traditional top-down story of ideologically-driven ‘reforms’ from both the left and the right, and I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Sticking with the more academic end of the spectrum, I also enjoyed Helen Thompson’s Disorder: Hard Times in the 21st Century even though, as the title suggests, it’s much bleaker in tone. Truth be told, I don’t remember all of the threads of her argument but – if you remember one thing from Thompson – it’s the centrality of energy supplies and energy markets. In 2022, after the Russian shock to European gas prices and resulting political fallout in the UK and elsewhere, this was an easy lesson to remember.

On a very different note – although I can just imagine Helen Thompson in my ear pointing out how the whole Silicon Valley ecosystem was driven by the era of cheap money – it’s impossible not to be hooked by John Carreyrou’s Theranos thriller, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup. Part of the fun is that the story of the book itself is also the story of Elizabeth Holmes’s downfall. Often, you finish a book of contemporary non-fiction thinking “that’s so awful and intractable” whereas this year was the very year of Holmes’s guilty verdict and sentencing. Anyway, if you’ve been living under a rock: Elizabeth Holmes tries to emulate Steve Jobs with a fake-it-till-you-make it approach to blood testing. But they never do make it, resulting in potentially catastrophic harm to patients, while anyone raising the alarm is hunted down by a company with a particularly ruthless streak. If you’re reading this, you’ve probably read this book already. But if you haven’t, it’s quite a ride.

Bill Bryson’s One Summer was quite different to what I was expecting, but nonetheless a fascinating tour of what was making waves in America during the summer of 1927. I like how it makes you realise how transient culture is: what is huge and important today may be totally forgotten tomorrow. Going much further back, I really did enjoy The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England. Sure, it is a little baffling for the author to pretend that he’s just invented the concept of exploring the past in the present-tense. People have fantasised about this for a long time. But while it isn’t novel, it is fun – especially for someone who never studied this period. From memory, I think I decided that my best bet would be to try and find a well-functioning monstrary. That is, if I’m not killed by one of the many ‘hilarious’ acts of random violence or cruelty which (allegedly) abounds in the medieval world.

I thought I had taken better notes on Early Greek Political Thought from Homer to the Sophists, but I did not. So it’s a difficult book to review because, of course, there were many different ‘early Greeks’ and they held many different views. Many were, dare I say, not as all-encompassingly terrible as Plato was. Most were, unsurprisingly, very sexist. Which brings me neatly to my final non-fiction book of the year: Caroline Criado Perez’s Invisible Women, about the “male as default” thinking which still pervades many aspects of our lives, including in critical data about the world.

I’ll come right out and say that this is a really good book, which is why I’ve seen others recommending it many times since it was first published in 2019. At the same time, it’s also a book where its real power lies in reaching beyond the small audience who will ever read it cover-to-cover. That’s why the anecdotes about car crash dummies modelled exclusively on male bodies, snow ploughing designed for male travel patterns and (in the most infuriating chapter of all) potentially life-saving drugs which unknowingly have entirely opposite effects on men and women all seem so familiar: it’s because you’ve heard them already in newspaper columns, podcasts and conversations inspired by the book.

Of course, a lot of its wider brief – especially on women’s unpaid care work – is hardly news to anyone who’s read anything similar before. But it would be a bit churlish to blame Perez for the intractably sticky nature of the problem. And this is a particularly good account, with a practical tone which balances an acerbic critique with practical, politically actionable changes – rather than the hand-wavy ‘any change will be illusionary until society is totally reimagined’ framing which is sometimes found in the final chapter of a book like this. I do wish we could have a moratorium on the kind of sentence where an author explains that, although change X will cost £Y, it would actually pay for itself over time because of Z. There’s almost no policy proposal which couldn’t be written in those terms, and the formulation is designed to hide trade-offs which are usually lurking in the background. But that’s one of the reasons this is such a good book. At heart, it’s a democratic argument – a majoritarian argument – because given that roughly half of humanity is female, the potential upsides to making better trade-offs are so enormous they will always be worth perusing. Even if it feels like you’ve read it before.