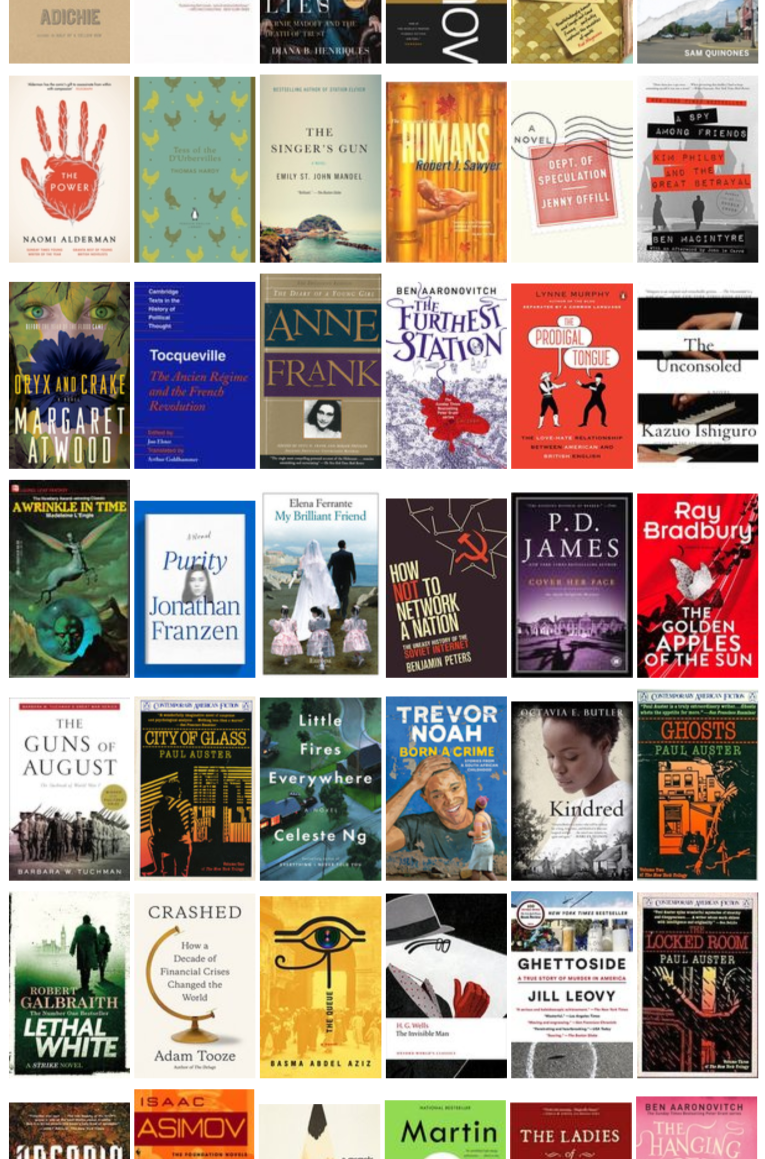

Time for the annual book review post, which has grown longer and longer since I started in 2012! For another year running I met my annual target – “at least one more book than last year” – by reading 42 books (a great number) in total. This was definitely made a little easier by having extra free time in December. For 2018 I also instituted an extra rule of alternating between male and female authors after noticing that last year’s bookshelf was pretty imbalanced in favour of men.

Since 2019 is going to be such a transitional year – with all of our travelling and moving back to London – I have decided to take a break from my reading rules and targets. I’m still planning to read – a lot! – but I’ll just see what comes naturally, and maybe go back to normal in 2020. And without further ado, here’s my 2018 bookshelf:

Fiction

I started the year with Americanah, which left me a little flat. People have been surprised by this, especially given how much I enjoyed Half of a Yellow Sun, and it’s not that I have any particular critique of the novel. It was well-written and enjoyable to read but just didn’t leave me with much afterwards. I then moved on to my traditional annual book recommendation from Todd, which this year was The Virgin Suicides. This was an unsettling read, clearly written in a different era, and the collective ‘us’ narrating the book is deliberately creepy. I have to say, I was never into the fetishisation of suicide which sometimes exists among teenagers, and structuring the book around the suicides of five sisters struck me as more totally horrific than maybe it does to a younger audience. Sticking with recommendations: I did enjoy Nina is Not OK, which came via Tash and felt very true to life.

The Power was excellent, centred around the very raw and mostly unspoken question: just how much of the modern relationship between men and women is based on the underlying awareness of physical strength? It reminded me a little of Exit West in that it uses a spark of sci-fi/fantasy to probe a big social question, but does so a lot more successfully. In a similar vein, I was excited to enter Margaret Atwood’s dystopian (and highly developed) world of Oryx and Crake and am looking forward to the rest of the series.

Let’s talk about Tess of the D’Urbervilles, because Tess’s life is really depressing… a shining example of when to just pack up and move to America. It’s impossible not to feel deeply for Tess and the unfairness of her life, and the force of fate which pushes her relentlessly from bad to worse to even worse, even though there are plenty of moments where things are – maddeningly – almost-but-not-quite rescued. The book also paints a vivid picture of English rural life – although, of course, I don’t feel the same sadness about its passing that Hardy does.

When it comes to Ishiguro I can’t stop myself working through his back catalogue, even when it means reading something as frustrating as The Unconsoled. It’s a dream world – that’s all you need to know. The kind of nightmare where space and time is all warped and you keep taking on new missions without ever completing anything. In comparison, I enjoyed reading Purity a lot more but it is also the weakest Franzen book so far, especially once it starts dragging in the second half with the memoir section. Also, can we please institute a complete ban on fictional characters in novels who are authors?

In contrast, Lethal White was so, so good and my favourite of the Cormoran Strike series so far. The novel was satisfyingly long, giving me more time with Strike and Robin after a far too prolonged absence, and the ending was less of a headtwist than usual… not that I saw it coming, but I felt that everything fitted together better plot-wise than the predecessors in the series. More please, JK Rowling, and soon!

I was a little disappointed that American classic A Wrinkle In Time is not actually a time-travel story (more of a space-travel story!) but it was cool as a piece of children’s fiction with a strong protagonist. The explicitly Christian message (and some overly obvious Cold War rhetoric) can be a little off-putting, and it is funny that the big bad is called IT, which now sounds more dreary than sinister. Sticking with the American sci-fi theme, The Golden Apples of the Sun – the third and final anthology by Ray Bradbury in the beautiful collection gifted to me by Katie a few years ago – was another amazing collection of short stories. Almost all of the stories manage to convey a complete, vividly-imaged world in just a handful of pages. The other short story collection I read this year was The Ladies of Grace Adieu, Susanna Clarke’s brief return to the world of Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell. I enjoyed these fairy tales, but I’m also up for a full-throated sequel.

I’m not really sure how I feel about My Brilliant Friend, which has been extensively recommended. The central characters were certainly interesting and I will keep reading the series to follow their lives, but I wasn’t nearly as gripped as many reviews suggested I should be. Similarly, Paul Auster’s ‘New York Triology’ (City of Glass, Ghosts and The Locked Room) are the kind of unsettling and frustrating postmodern books which are good to read occasionally, but I really don’t love, and I’m worried that the Amazon and/or Goodreads algorithm is going to start sending me more.

The book which really rubbed me up the wrong way, however, was London Fields. I had enjoyed Time’s Arrow so picked this up as my next Martin Amis novel. It is, supposedly, regarded as his “strongest”. But it’s a car crash. Yes, it is well-written, but the good writing is just directed at being snide and cynical for no real purpose. It’s also endlessly racist and misogynistic. At this point I can imagine Amis popping out to complain that I’m being unfair because it’s the narrator character who is racist and misogynistic, not him. No dice. All the vitriol does nothing other than to furnish a vague and confused “state of society” critique for the “end of the millennium” [sic] which had already dated very badly by the end of the actual millennium since the book was written in 1989, anticipates literally nothing of the 1990s and anachronistically chucks in threats of a nuclear war between the Cold War superpowers.

OK, assuming I’ve persuaded you not to read that, what should you read instead? Kindred (a time-travel story from 1979 about a black American woman who finds herself back in a nineteenth century slave plantation) is powerful and very brutal. The Queue is both Orwellian and Kafkaesque, but set in a modern day Middle Eastern bureaucracy which is clearly Egypt. And I want to put in a good word for HG Well’s The Invisible Man, which is a short, fun classic of sci-fi about (unsurprisingly) a man who manages to turn himself invisible. Unfortunately, he turns out to be the worst, most petulant guy imaginable so the opportunity for superhero stunts is entirely wasted.

Finally, a few words for the authors who always make it onto this list. I planned to read Asimov’s classic Foundation years ago but decided to methodologically work through his interlinked Robot and Empire series first. This year I finally got there and while the underlying premise is slightly bonkers, I am reassured to have many books left in the series to enjoy. And I have almost caught up with Ben Aaronovitch’s Peter Grant series! The sixth instalment, The Hanging Tree, felt a little rushed at the end but did move the overarching plot along significantly and entering this world is always a treat.

Non-Fiction

A couple of my favourite non-fiction books this year have been recommendations from Vox’s The Weeds podcast, starting with Dreamland. It tells the intertwined story of the rise of opioid prescribing in the United States (most notably OxyContin) and, simultaneously, the revolutionary ‘customer-centric’ approach of the Mexican heroin trade, for example through salaried dealers who have no incentive to dilute the product. The result has been an opioid epidemic of devastating proportions. An excellent read – perhaps the only thing missing is a deeper examination of the origins of the physical pain driving the initial prescriptions in the first place.

Similarly, Ghettoside told a simple but effective story about murder in the most violent areas of LA. While many people are familiar with police violence in black communities, the other side of the same coin is chronic under-policing where it really matters. Clearance rates for murder are shockingly low, and we know from research that consistency of punishment is much more important for reducing crime than the harshness of the penalty. The homicide detectives in the book have low status even within the LAPD, but justice can’t be done without them. All in all, along with the powerful stories of wasted lives, the book is a good rebuke to the idea that only preventative policing is valuable.

I also really enjoyed Crashed by Adam Tooze – although that’s unsurprising, since I always enjoy his work. This book runs through the decade following the 2008 financial crisis, and the most memorable theme is the poor preparation and reactions of European institutions in general and Angela Merkel in particular. I think perceptions of Merkel are rose-tinted in a world of Trump and Brexit, and she may be personally sympathetic, but it’s still amazing to contrast Europe with the US Federal Reserve. The consequences (most obviously in Greece) have been dire.

I read A Spy Among Friends – about the notorious spy Kim Philby – after being inspired by a John le Carré novel a few years ago. It’s really just totally crazy that the guy running anti-Soviet intelligence for Britain was a Soviet spy the whole time. Astonishing. Sticking with a Soviet theme, How Not to Network a Nation is an interesting story about the aborted creation of a Soviet internet to manage the economy. It reminded me of an Asimov short story about globalised central planning by computer. At the same time, this is very much one of those academic books to which someone has given a snappy title and slapped a nice cover on. I could have done without the repetitive pondering.

The Guns of August is a classic of popular history, but I was expecting something more political. Instead, most of the book is taken up by the military history of the first months of the First World War, and the events which quickly led to a stalemate with no decisive victory for either side. Interesting, but not really the focus I wanted. On the other hand, Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl was absorbing and a really emotional read. Obviously you feel really badly for Anne’s mother, who is treated pretty harshly by her daughter, but I don’t think that makes Anne ‘unlikable’ as opposed to a teenager who was robbed of the time to grow up. The worst part is getting to D-Day: she is so excited that the invasion has begun, while the reader is just counting down the months until August when the family are discovered and the diary stops.

No, I haven’t read Democracy in America yet. Yes, it’s on my list. As a warm up, I read Tocqueville’s The Ancien Régime and the French Revolution instead. His writing (at least in this translation) is very fresh and easy to read, and the key point is worth repeating: “it is not always going from bad to worse that leads to revolution… the most dangerous time for a bad government is usually when it begins to reform… every abuse that is eliminated seems only to reveal the others that remain”. (Admittedly the logic for rulers of bad governments is not great.) Equally, his passage on the feudal nobility – who once possessed greater privileges, and yet were less unpopular because they provided services in return – has interesting implications for government today.

Tara Westover’s Educated (yes, the book on every reading list) was not quite the memoir I expected. Based on her interview on the Talking Politics podcast I was anticipating an upbringing which was extremely cut-off from the rest of the world… but not necessarily one which is so straightforwardly violent and abusive.

Finally, I really loved The Prodigal Tongue, a book about American and British English which grew out of Lynne Murphy’s awesome Separated by a Common Language blog. It’s so nice to read a non-alarmist, well-informed and evidence-based exploration of English in two countries by someone who obviously loves language. Better than 95% of anything else you will read on the topic.

One Comment on :

2018: My Year In Books