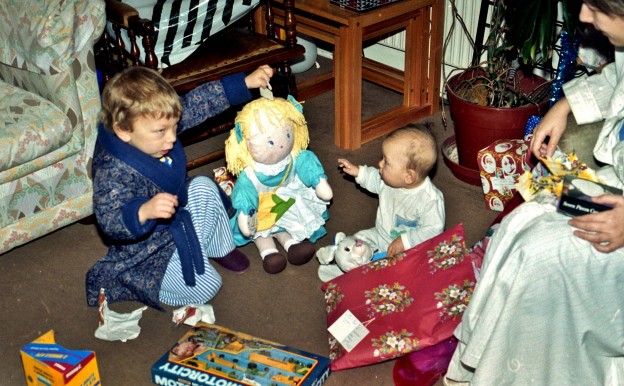

I’m an archivist at heart – as is painfully obvious from this blog – so it’s not surprising that for years I’ve wondered how best to digitise our family photos. Both my parents took photos as we grew up. The best ones made their way into big, clunky photo albums where each page is covered in scanner-unfriendly cellophane. But luckily, my mum’s inner archivist nerd also led her to stash away all the original negatives in a big box at the back of a cupboard. On top of that, I have a bunch of photos from my own camera (I was documenting things early – my first camera was in the shape of a clown) which were sitting precariously on a shelf alongside Junior Monopoly and Frustration.

Throwing a tantrum at the lack of digitalisation

I knew I had neither the time or the expertise to tackle this myself, so went in hunt of something online. I ended up going with Scan Van largely because of Alan’s collect and return service. Sending all our family negatives off in the post left me a little queasy, so having someone turn up to take the lot in person was a big win. The whole process took a couple of months (although I made it clear I wasn’t in a rush) for a total of around 4400 photos, the vast majority from film negatives.

I believe this is for you

It’s not a cheap undertaking, although the price (less than £1500) was absolutely worth it for the results. I’m so happy! Everything is now digitised, correctly-rotated and colour-restored. Apparently the total cost for the average family is lower anyway, as negatives are much more expensive and time-consuming, as well as being susceptible to dust and scratches. (I have to say, as soon as you start looking through them you stop noticing that… we’re going for family memories here, not Ultra HD.)

Katie vs. the bin (part #329)

So, bottom line: if you’re thinking of doing this and want someone recommended, Scan Van is an excellent choice if you’re within its range 😀

(Rest assured I have Twitter pinned)

(The name itself is probably a mistake, by the way. Not only is it unlikely to excite consumers much but it’s also nothing like Windows – although I suppose once Windows 8 comes around it might.)

Anyway: a major factor in all of this is obviously cost, and I’ve always preferred to be on SIM-only deals rather than long-term contracts because they seem to be much better value. Virgin, for example, will give you 500 minutes, 3000 texts and 1 GB a month for around £15 a month – and you can cancel whenever you like. But buying an unlocked iPhone outright is, what, around £600? I bought the Optimus 7, on the other hand, for £200 – and the hardware feels nice, too.

But it’s the software that really matters, and although it may just be a matter of taste, I generally prefer the quite innovative feel of the Windows Phone to everyone else’s rows and rows of icons. Integrating services together makes sense, too: my Facebook account has pictures for everyone and my Outlook knows their phone numbers, so why not link them all together and combine all the information seamlessly? Touching, typing and scrolling all work well, although there are a couple of strange failings, like calendar text which is far too small to read and no custom ringtones. (This latter one is being fixed, though.) Also, I don’t know how common this is across all smartphones, but it’s silly that the phone’s alarm can’t turn the phone on.

Plenty of commentators have said the same thing: that the Windows Phone is a decent smartphone platform that’s just too late to the game, and can never catch up with the others. They might well be right, and if you want the widest choice of apps then you need to look elsewhere. But aside from that, it doesn’t really matter a great deal. Most of my mobile data (contacts, calendar, e-mail, Twitter etc.) is either in the cloud* or synced with my laptop or both, and I could just as easily switch to another smartphone in the future without much hassle. For the moment, though, Windows Phone 7 genuinely offers something both new and a little delightful.

(*In the cloud with Google, mostly. Just because I’m on WP7 doesn’t mean I want Windows Live handling everything.)

OK, regular readers: stop right here. This blog post isn’t meant for you. The only reason I’m putting this out there is because it took me two days to figure it all out for myself, and although certain forum posts found through Google helped me along the way I’ve not yet seen any comprehensive guide to recovering files from corrupt Norton 360 backup disks. It certainly would have sped things up ![]() So, if anyone else finds themselves in the same situation, this is for you!

So, if anyone else finds themselves in the same situation, this is for you!

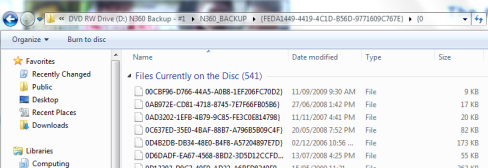

Here’s the background. A couple of days ago, a relative inadvertently wiped the data from her PC. Although she had a three-DVD set of a Norton 360 backup, they were refusing to restore anything and Norton’s technical support were – apparently – less than helpful. (Judge for thyself.) I didn’t want to poke around the PC, since I’m not a data recovery expert and didn’t want to overwrite anything, but did bring home the DVDs to have a look if anything could be salvaged.

This is a sample of what was on the disks:

Useful?

However, after searching about some more, it turns out that these backup files were simply the original files but without their file names or extensions! (So much for ‘encryption’ ![]() )

)

So, as promised, here’s how to restore at least the file contents:

1. Copy all of the backup files into one folder on your hard drive.

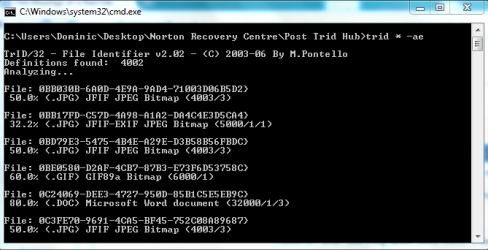

2. Download the supremely excellent TrID, by Marco Pontello. Note: for Windows, and I’m kinda assuming you are a Windows user here, given the circumstances, you’ll need to download both the Win32 zipped package and the ‘TrIDDefs.TRD’ package of file definitions from the bottom of the page.

3. Extract both of these zipped packages into the same folder housing your backup files.

4. Open a command line window at this location. Note: on Windows 7, the easiest way to do this is by holding down the shift key as you right-click on the folder. Then select ‘Open command window here’.

5. Type ‘trid * -ae’ (no quotes) and press enter.

At this point, TrID will run through all of your backup files and attempt to restore their extensions. If you have a large number of files, this may take some time, but it should be obvious that it’s working:

TrID running

P.S. I really don’t recommend you use Norton 360 as a backup solution…

P.P.S. A minor point, but yay once more for Windows 7! For a task like this, little things like grouping and moving files by certain criteria are just extra-easy.

P.P.P.S. If I do get any payment for this, I will definitely be giving some to Marco Pontello, promise.

Just back from Bill Thompson’s talk on the ’10 cultures problem’: a restatement of CP Snow’s famous divide between the arts and the sciences, but this time between those who understand computer code and those who don’t. (That’s ’10’ in binary or ‘2’ in decimal; I understand this because Daryl taught me about binary numbers whilst sitting around the dinner table many years ago, all of which rather pays tribute my parents’ ability to persuade clever people to talk to us.) Anyway – the point is that without an understanding of how systems work, people are powerless to make informed decisions about how those systems should be applied within society. And with computing very much at the heart of what we all do, this matters.

I don’t disagree, but I think it’s just one manifestation of a much wider and long-running phenomenon: the tension between specialisation and universality in a world where the former promises great power and the later may be the only real safeguard against its abuse. You can, after all, set up a similar ‘two cultures’ paradigm about many things – between those who understand the process of experimentation and those who don’t, between those who can use rhetoric and those who can’t, between those with mechanical engineering prowess (building, plumbing – the things I tend to call ‘real skills’ ![]() ) and those with none whatsoever. I understand that the challenge is not to turn everyone into an expert on everything but merely to be able to understand what the experts are doing, and how they are thinking, but experience doesn’t seem too encouraging.

) and those with none whatsoever. I understand that the challenge is not to turn everyone into an expert on everything but merely to be able to understand what the experts are doing, and how they are thinking, but experience doesn’t seem too encouraging.

Nevertheless, life is not binary and we don’t have to accept a straight choice between ‘expert’ and ‘know nothing’. CP Snow bemoaned the fact that an ignorance of the Second Law of Thermodynamics would not prove embarrassing to members of the literary elite, and I assume that today many people still wouldn’t have much of an idea. (Including me: I ‘know’ what entropy is in a very general sense, but I couldn’t go into many details.) But, thinking about it, perhaps there are a fair few non-scientists who would have some inkling. And in the networked age it is phenomenally easy to learn just a little bit more. Perhaps the best we can hope for is the mass curiosity, will and means to research new areas of knowledge over a lifetime: it won’t lead to everyone understanding code, but maybe just enough to discuss it at dinner parties.